Mystical Experience, Psychedelics, and Dragons

Freedom from conceptual prison

Long ago

in ancient China

a man loved dragons

so much he filled his house

with clay statues and pictures

of the wonderful beast

and talked endlessly

about dragons

to everyone he met.

Then one day a real dragon

who had heard of the man's love

of dragons was flying overhead

and decided to pay a visit

so the fellow could meet

an actual living dragon

but when he stuck

his dragon head

into the man's window

the dragon-lover

screamed in terror

and ran away.

Belief in God

and disbelief in God

are harmless hobbies

but an encounter

with the Divine

can shatter

your ego-mind.

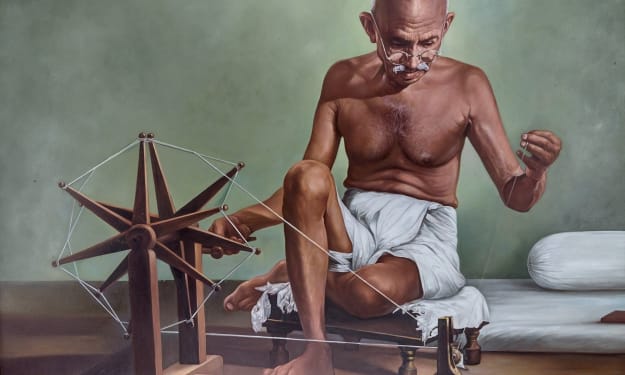

Inspired by an ancient Chinese fable

Full Disclosure: I met a dragon 53 years ago under the influence of a psychedelic plant. That encounter, the most significant event of my life, demolished my militant atheism and set me on a lifelong course of spiritual exploration through meditation and other non-drug spiritual practices.

---

I recently read, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, by influential American philosopher Daniel Dennett. The author spends 448 pages debunking religion without mentioning mystical or spiritual experiences. This is like writing a review of a restaurant without mentioning the food.

Spiritual states of consciousness have played an important role - often a founding one - in religions throughout history. Various methods have been used to achieve such states, including prayer, meditation, fasting, chanting, dancing, drumming, deliberate physical pain, sensory deprivation, and mind-altering substances. Ironically, established religions often persecute people who have experiences similar to that of their founders.

Mystical states of consciousness, the most powerful and life-changing type of spiritual experience, typically involve intense contact with a Spiritual Force, a sense of oneness with everything, and the feeling that love permeates the universe. Mystical experiences can occur spontaneously, as the result of spiritual practices, or from the use of psychedelic substances.

Neuroscientist Sam Harris, an advocate of mindfulness meditation, describes the power of mystical states induced by psychedelics:

…. if you get a glimpse of the beatific vision, you will know that it is possible to enjoy an utterly transfigured experience of the world and even to lose any sense of separation from it. And you will know that consciousness in this moment is truly sacred. (The Psychedelic Paradox, a 10-minute audio)

He also says that after a sufficient dose of psilocybin mushrooms or LSD, it becomes absolutely clear that:

…. you have been living in a kind of prison and once the drug wears off and you're returned to that prison you can't quite convince yourself that it's good to live there. If you have a truly liberating experience on psychedelics, it is difficult not to view a conventional sense of self as a form of mental illness.

Harris goes on to say that psychedelically induced experiences often motivate people to meditate - people who would otherwise consider it a waste of time because they would be skeptical that anything profound exists beyond conceptual thought.

But he stresses that the purpose of meditation is not to achieve psychedelic-like pyrotechnics, but rather to enjoy the freedom that comes from experiencing consciousness prior to identification with thought.

Daniel Dennett, defender of conceptual thought and the usual sense of self, has dedicated his life to scientific materialism, the view that everything can be reduced to physical matter. God is an illusion, mystical states are hallucinations, zero angels dance on the head of a pin, and dragons do not exist.

Dennett wants to free people from superstitious beliefs and religious dogma - a worthy cause - but he does not go far enough. He himself appears imprisoned by mental concepts, specifically the conceptual framework of materialistic philosophy.

Eckhart Tolle and other mystics tell us that true liberation is not just from religious, political, scientific, or any other form of dogma, but from excessive identification with the thinking process itself. As adults, we are trapped in the cage of mental chatter, our consciousness dominated by thoughts about thoughts about thoughts, always focused on the past and future.

Tolle explains (Become Free From the Over-Thinking Mind, video) that conceptual thought is an amazing tool, but identification with it blocks us from being awake in the Now, the only place life can truly be lived.

He describes with remarkable clarity how we are consciousness itself, prior to the arising of thoughts and other mental forms, and that as we identify with this formless awareness, we experience peace, compassion, joy, and wisdom. As that happens, conceptual thought becomes a servant of our authentic self, rather than a distracting - often destructive - monkey jumping from branch to branch.

I googled 'Daniel Dennett and psychedelics' to see what his position was on this increasingly mainstream source of reported mystical experiences. I did so because Sam Harris - Dennett's fellow leader in the new atheism movement - speaks so glowingly about psychedelic states of consciousness, and I figured Dennett would have an opinion.

(By the way, Harris's beatific psychedelic experiences have not budged his atheism. But this is not as strange as it sounds. For example, Buddhist meditators who experience profound mystical illumination, such as satori, remain non-theists. Apparently, the dragon they encounter is formless!)

My google search revealed that Dennett has never used psychedelics, although they have been offered to him often. He believes they are risky, and he is quite content with his current state of mind. (Dennett Explained: An interview with Daniel Dennett August 2019).

This reminds me of Galileo and those who refused to look through his telescope. Only this time, it's the person advocating science, Dennett, who refuses to look through the psychedelic telescope.

Is he afraid that a mystical experience might turn his life's work to dust?

That's what happened to St. Thomas Aquinas, one of the greatest theologians of the Catholic Church. He had a spontaneous mystical experience late in life that convinced him that his intellectual accomplishments were not important. As a result, he left his masterpiece, Summa Theologiae, unfinished.

Aquinas uttered words that put words in their place. "All that I have written appears to be as so much straw after the things that have been revealed to me." (Lives of the Saints, Alban Butler). Such is the power of mystical experience to obliterate conventional notions about what is important.

Conceptual thought, that amazing but tricky tool, can not only block contact with the present moment and with mystical states, but it is also used by ego to rationalize any belief and justify any behavior. Which is why it should always be taken with a grain of critical - especially self-critical - salt.

Aquinas devoted himself to proving that God exists, while Dennett has worked diligently to prove the opposite. Ironically, both men were apparently too caught up in their thoughts about dragons to ever actually meet one - until the very end, in the case of Aquinas.

Fortunately, we can all invite a dragon over for dinner through mindfulness meditation, other spiritual practices, or responsible use of psychedelics. But we must be prepared for our rude guest to devour, digest, and transform us.

---

For the latest research on the use of psychedelics for healing and spiritual self-exploration, see the four-part Netflix documentary, How to Change Your Mind, based on Michael Pollan's book, How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence.

About the Creator

George Ochsenfeld

Secret agent inciting spiritual revolution. Interests: spiritual awakening, mindfulness meditation, Jung, Tolle, 12 Steps, psychedelics, radical simplicity, ecological sanity. Retired addictions counselor, university faculty.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.