She believed herself to be in half. A line was drawn in pencil all the way down through her middle. Perfectly in half. Joined. Half could be felt more than the other. Stretched out, vibrations moving just beneath her skin, a warmth. She had finished only half of her yoga session in the morning, her new routine rushed due to a misreading of time. Each morning began with her alarm and a mental note. Just get to the mat. Drink a glass of water. She was proud of sticking to this ritual; finally committing to daily steps to help her to feel whole. Yes, she was in half. Not quite stretched, not fully shaped, breaths only partly finding spaces of her. She wondered if other people would notice.

She would find someone to tell. Her thoughts needed to be released. Otherwise it felt as though an endless, incoherent novel was writing its self in her head. The someone she told, would smile, pleased for the distraction from work. To stretch a few centimetres away from the things they had to do between 8:45am and 5:00pm. Earlier than that and later than that for her. She held the keys, she turned off the lights, she made sure everything ran smoothly. It pleased her to make the place friendlier with these little interactions.

She liked her work. It was fun, especially since she had shrugged off ambition. She focussed now on the task in front of her. The meaning of it. The purpose and good of it. She listened, one Saturday afternoon, to a musician being interviewed. He talked about doing whatever it is in front of you and do it well. Throw yourself into it with all your might. So she did. Every day. As a result, she enjoyed it all the more and felt something like luck, like gratitude, to be doing it. She kept her mantra, do what is in front of you and do it well, tucked safely in her chest, pounding away to keep her blood flowing.

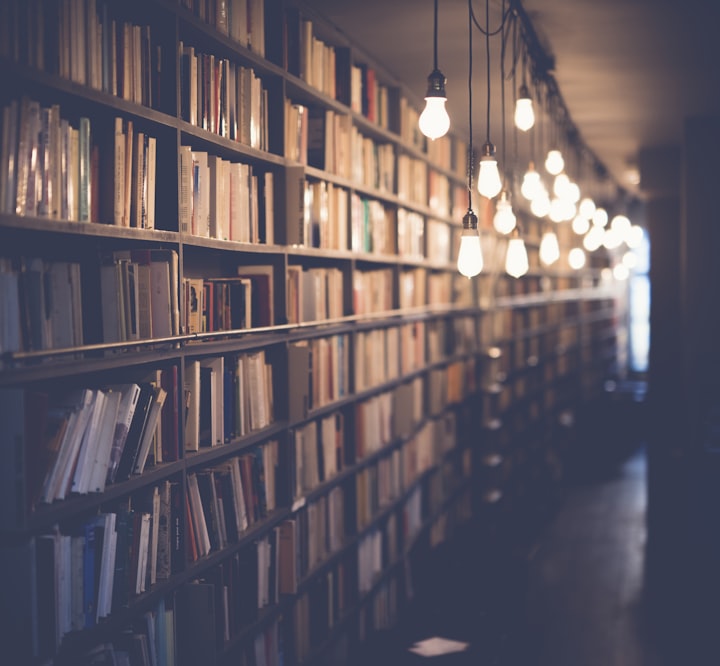

The small bookstore was made up of a few staff who had also been there a long time. Like the rusty coloured bricks that held it together. Its mortar holding, a little dusty if you were to brush against it, crumbly if you were a mouse scratching to make a home. The floor creaked in more places these days and the steep, narrow staircase felt like it could hold each footfall as long as you were careful, as long as you didn’t think too much about the age of the timbre and of all the feet that have landed on the slightly sloped steps, shiny now with wear and age. They too creaked in places. Those bricked walls were covered in too high shelves that appeared to lean forward; a bow to greet you, the nosy top shelf peering down saying hello. Somehow, the books stayed in place. Partly because they were so packed in. It looked like chaos but there was order. Order and beauty. The musty smell of old pages, filled with stories and ink, dust coating the spines of books placed on their sides so they had a spot to sit. Waiting to be found and opened again. The thing about these bookstores, is that the people in them don’t like to part with the books but they love sharing the thrill of a good find, a conversation with people who love books like they do. There are others who do not want the words to read, they want the beautiful, old, and regal like spines by the metre to decorate a set, to fill a shelf and to be “aesthetic”. A photo on Instagram. The floorboards had gaps between them, wide enough to lose a coin in some sections, covered in threadbare rugs in others. The place was magic. It smelled of plunger coffee in the mornings before 10 and tea every hour after that. Crumbs of Jam Fancies on the counter at 11. They too, the people who worked there, were enchanted by it. They had no plans to leave. They too found meaning in the work, in the community. They were part of its magic.

So when the news came that it was to close, no one believed it. No one wanted to believe it. No one had any idea of what to do or what life would be like without it. Before something ends, or someone dies, you cannot appreciate what you need to say, what you need to hold onto, what you need to remember with all your being, or what to really, truly enjoy. It is impossible. It ends. They end. A story finishes. The loved one dies. Then you know it. Then, cruelly, a list forms in front of your eyes and you see what you should have listened to, what you should have asked, what you should have paid attention to. This all comes after. Hindsight, that prankster. So, when the news came, not knowing hindsights prank was teetering above their heads, balanced on the doors edge, they did nothing. They continued as normal. What else could be done.

She didn’t do much either. She knew better than them what was coming but decided to play along, as much to protect them as to protect herself. Protect herself from accepting what she had realised months, probably years if she was truthful, earlier. It couldn’t last. This grown-up play they called work. It was a wonderful theatre and the play was perfect. For them.

A few days before the last day, after the day she felt in half, she rode her bike through green, leafy streets. She rode along them but it felt more like through. Napier Street was like a tunnel. She always slowed to take it in, look at people enjoying themselves and company in autumn light against bluestone and draped over trees, the green leaves a bright contrast to the blue grey stones. It reminded her of her brother whom she missed, of the croissants they shared and the coffee they drank at the small round tables. And of her father when they ate cheese and salty, thin meats and plump olives while they waited for her mother to recover in hospital nearby– saved again. More time with them, precious time.

She peddled harder coming up around past the Town Hall, memories of a drunken night on that wedge of lawn, before the fairytale statue was placed there as guardian of fun, reckless nights. A possum came sprinting down the street to her right. A possum! she shouted to terraces. She thought at that moment about noticing, of paying attention, it gifts you with sights such as a possum in the daytime, running like it is late for an important date, down an empty Fitzroy street. She remembered later that she had forgotten to tell anyone about it. The memory would be hers and the possums.

Curving around the corner and over cobbled lanes, she reached the bookstore. It’s lock too high for her she stood on two bricks to slide they key in. She heard a thud. Then another. Looking up, she saw movement behind the grubby glass of the small window near the door. Then thud. Feathers against glass. She carefully edged the heavy red door with her hip and peaked inside. The bird had landed on a shelf beside a struggling monstera with its generous hands out as if it was trying to catch the poor, lost thing. It was stunned but not dead. Her second animal encounter of the day. She put her bag down by the door, opened the door fully, her bike resting against the outside wall. She crept toward the bird. Are you ok? Little bird? Almost expecting it to answer, wondering if it might be her mother who she thought of often of as a bird, she looked more closely then scooped its warm body into the cup made of her hands. She carried it with all the care she had inside her to the counter and placed it down. It moved a little. She found a box with receipts and scraps, so tipped some on the floor leaving others to act as a nest. Sliding the box nearer the bird, she put it in its special bed. She felt proud of her efforts. Saving this small creature. Remembering her bike, she went to bring it inside. With a tinkle of the stores bell, the bird took flight. Recovered. It flew madly around the room, not learning from its previous error, smacking into one window then another, this time unharmed. Then it stopped. Perched on a high shelf. Challenging her, to come at get it. To join her on the perch. She moved the shelf ladder across and climbed. A jam fancy crumb in her hand as an offering. Nearing the bird, it watched her. She reached the top. Then, taking a crumb from her hand, it flew off, down and out of the still opened door. She slipped a few rungs and holding her grip on one rail, she grabbed hold of a shelf, knocking books to the ground. A new type of thud. And a plume of dust. She climbed the rest of the way down, to pick up the books, to clean up the carnage left by the bird. Between two heavy books a shiny leather cover peaked out. A slim, little black book. A moleskine. She hadn’t seen it before. It looked old but cared for. Picking it up, she found it was smooth and clean. Pages still crisp. Ink inside. Handwriting she didn’t recognise – curled like her grandmothers – no one from the store wrote like that. That kind of handwriting mostly gone now. Extinct. The note was blunt.

Money. There is money behind shelf 12. Find it. Keep it or give it. Yours to choose.

She laughed remembering Arrested Development, there is money in that banana stand, before looking again. Shelf 12. The shelves did have numbers on them, used long ago. Not far from the window the bird had hit, she found it. She knew this place like her own home. She tried budging the shelf to move it forward. Too heavy to shift stacked with books. One by one, she worked quickly to take out each book. Her own pile of brickwork. Behind the third shelf, she saw a gap in the wall. A brick removed. She reached in, mortar crumbling like ash over her hand, she found a tin. Then another. Then another. Then another. All pushed and stacked like the books in front of them. The books that kept them protected and hidden for who knows how long. In them, as the little black book had said, there was money. Sitting on the floor among the mess, aware that soon the store would be filling with her co-workers and regulars, she counted. Five, then ten, then 20. Thousand. $20, 000. The words on the page of the book, repeating in her head. Keep it or give it. Keep it of give it. One by one, she placed the tins in her bag. Money safely back inside. Lids clicked shut. The thought of the bookstore closing, the conversation she had had with the bank, the debts unpaid, the owner selling up, a development considered, apartments most likely, the magic fading, swam in her head. That novel starting back up. She picked up her heavy bag, the box nest still on the counter, and put it in the basket of her bike. Lifting it, she felt stronger than the morning time, she wheeled it out past the shelves, past the bricks and onto the street. Looking back, a hand against the red of the door, she pushed it and it closed with a thud. Then a click. Lifting one leg over the green frame of her bike, she tapped on her helmet three times and rode away. Fast as fast could be.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.