Beyond Boundaries: Rethinking the Brain, Genomics, and Sleep

Unveiling the Hidden Complexity of the Mind, Parasitic Genomes, and Sleep's Evolutionary Secrets

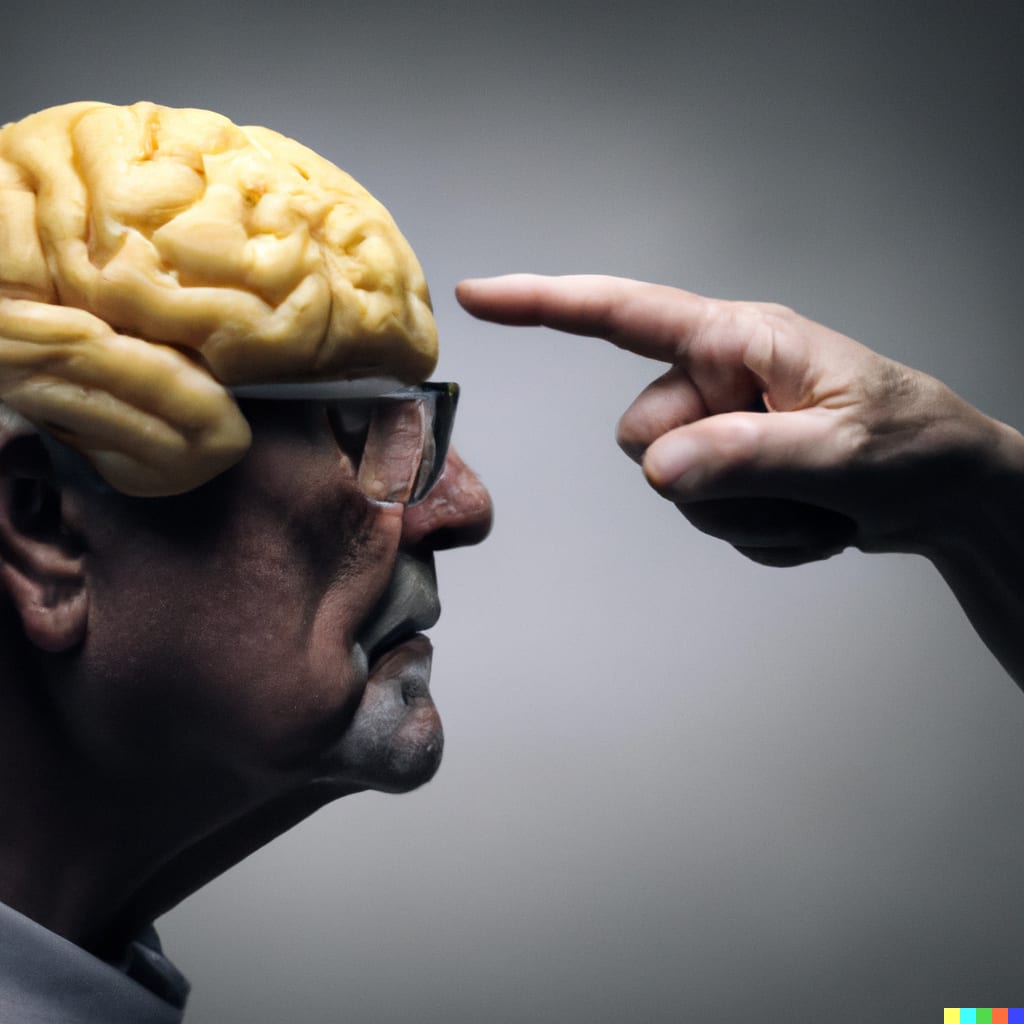

For centuries, the human brain has been a subject of fascination for doctors and scientists, seeking to unravel its mysteries. How is it organized? What roles do different areas play in mental functions, and how do they connect to shape our subjective psychological experience? Over the past 100 years, neuroscientists have approached the brain as cartographers, mapping its features and activities within defined boundaries. The prefrontal cortex has been hailed as the seat of rationality, while the motor cortex governs movement coordination. The somatosensory cortex and parietal lobes control our perception of the physical world, and the temporal lobes process memories, language, and emotion. The occipital lobe handles visual information, and the cerebellum executes motor commands. However, recent studies challenge these neat categorizations and reveal overlapping activity across different brain regions, blurring the lines of the traditional map.

The conventional conceptualization of the mind and its functions falls short in explaining the brain's complexities. Russell Poldrack, based at Stanford University, takes a computational approach to understanding how the mind is organized. Through collecting data from a variety of psychological tasks and employing machine learning, Poldrack's lab discovers neural activity related to memory recall that defies established categories. This realization prompts a fundamental rethinking of how we perceive the brain's functions. Within neuroscience, there is a consensus that the brain operates as a computational machine, requiring comprehension of the computations it performs. The challenge lies in finding a language beyond mathematics to describe these computations in human-understandable terms.

In the depths of Southeast Asia's jungles resides a peculiar flower known as Rafflesia arnoldii, or the "corpse flower" due to its putrid scent that attracts pollinating flies. This enormous flower, comparable in size and weight to a small child, is not only a captivating sight but also a parasite. Rafflesia extracts nutrients and water from other plants, often resulting in the incorporation of alien genetic material into its genome, frequently sourced from its host. The prevailing hypothesis suggests that parasitic plants pilfer from their hosts as a survival strategy. Liming Cai, among a lineage of biologists, takes on the arduous task of sequencing Rafflesia's notoriously complex genome. The genome's highly repetitive elements called transposons, colloquially known as jumping genes, pose a challenge akin to assembling an identical jigsaw puzzle. In collaboration with a bioinformatics team, Cai successfully constructs a draft genome for a Rafflesia species, revealing astonishing findings. Nearly half of the conserved plant genes are absent in Rafflesia, marking a record-breaking revelation. Furthermore, an astounding 90% of Rafflesia's genome consists of repeating DNA, a peculiarity that may revolutionize our comprehension of parasite genomics.

Advancements in genome sequencing technology allow scientists to explore the diverse branches of the tree of life, where rules can be bent through creative strategies. Nature's abundance often surprises, challenging our preconceived notions. Sleep has captivated researchers since the early 20th century, who primarily approached it as a neurological phenomenon with its purpose and structure rooted in the brain. However, observations of sleep in organisms with less complex nervous systems, such as cockroaches and hydras, have shattered this brain-centric view. Hydras, possessing nerve nets instead of a brain, have been shown to sleep, indicating that sleep predates the evolution of brains. This discovery has prompted scientists to reevaluate the purpose of sleep. Increasingly, they explore the reciprocal relationship between the brain and peripheral tissues, examining how sleep regulation affects the body and vice versa. The hypothesis arises that sleep aids in repairing damaged circuits, reducing activation energy and supporting essential functions that would otherwise be impeded during wakefulness. This growing body of evidence suggests that sleep initially evolved to regulate metabolism and facilitate repair before assuming brain-related functions.

As our understanding of the brain, plant genomics, and sleep deepens, we confront the limitations of conventional frameworks. By embracing new perspectives and incorporating emerging research, we stand on the brink of transformative discoveries that challenge our existing knowledge. The future promises to uncover the intricate workings of the brain, the mysteries of genomic adaptations, and the multifaceted role of sleep in maintaining our biological harmony.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.