Between faith and desire: How Moroccans use taweez for love

Practices from Africa

In Morocco, the practice of using talismans - taweez (locally referred to as ḥijab, taʿwidha or ḥadra) forms part of a wider ecosystem of folk Islam deeply rooted in Maghrebi history. Unlike amulets used for protection, livelihood, or healing, love-oriented taweez represent a distinct subcategory shaped by emotional vulnerability, social pressure, and gendered expectations. Across Arabic-language forums, the most frequent requests related to love taweez come from women aged 18–45, reflecting a demographic that faces strong cultural expectations around marriage, partnership stability, and family reputation. Fieldwork conducted in Moroccan universities on fqih and fqiya practitioners shows similar patterns, where requests concerning “bringing back a beloved” or “securing affection” constitute a significant portion of informal ritual consultations.

Historical Background: Origins of Taweez in the Maghreb

The use of written amulets in Morocco predates Islam and draws on a layered history where Amazigh protective symbols, Qur’anic textuality, and Sufi manuscript traditions gradually converged. Archaeological and ethnographic research from the Bibliothèque Nationale du Royaume du Maroc and French colonial archives documents how pre-Islamic Amazigh communities used leather-bound scripts and geometric signs for protection and fertility, many of which later became embedded in the Islamic ritual practices. With the spread of Islam in the 7th–8th centuries, Qur’anic verses, divine names, and Arabic letter-magic (ilm al-ḥuruf) began to replace earlier symbols, creating a hybrid protective repertoire rather than erasing local traditions.

From the 16th to 19th centuries, Sufi brotherhoods such as the Tijaniyya and Qadiriyya played a decisive role in formalizing amulet practices. Manuscripts attributed to scholars like al-Buni, particularly Shams al-Ma'arif and related derivative works circulating in North Africa provided systematic models for letter squares (awfaq), talismanic grids, and invocations. Copies of these texts, preserved in Moroccan university libraries and digital manuscript repositories, show that amulets were used primarily for protection, healing, and securing livelihood, with love-related uses appearing later as a more specialized subset.

French-language ethnographies from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, along with modern Arabic studies of marabouts and fqih practices, describe a consistent pattern: taweez evolved as a socially embedded “technology” of managing uncertainty. Although early records focus mainly on protection from spirits and envy, they also note that emotional and interpersonal concerns like courtship, marital harmony, fear of abandonment gradually became prominent motives, setting the foundation for the emergence of love-specific taweez in Moroccan society.

Categories of Moroccan Taweez and Where Love Taweez Fit

Contemporary Moroccan practice distinguishes several functional categories of taweez, each tied to specific social needs and recognized both in scholarly fieldwork and in practitioner testimonies. Ethnographic studies of marabouts in Fes, Marrakech, and Tetouan consistently identify four major types: protective, healing, livelihood-oriented, and relationship-oriented amulets. Protection taweez aim to counteract ʿayn (evil eye), sorcery (sihr), or jinn disturbances—topics widely discussed in Arabic ruqya forums and addressed in fatwa responses from Dar al-Ifta al-Maghribiya. Healing taweez are typically used for chronic ailments, often written with saffron ink and washed into water to be consumed. Livelihood-related taweez address economic insecurity, job prospects, or family welfare and are common in rural areas and weekly souks.

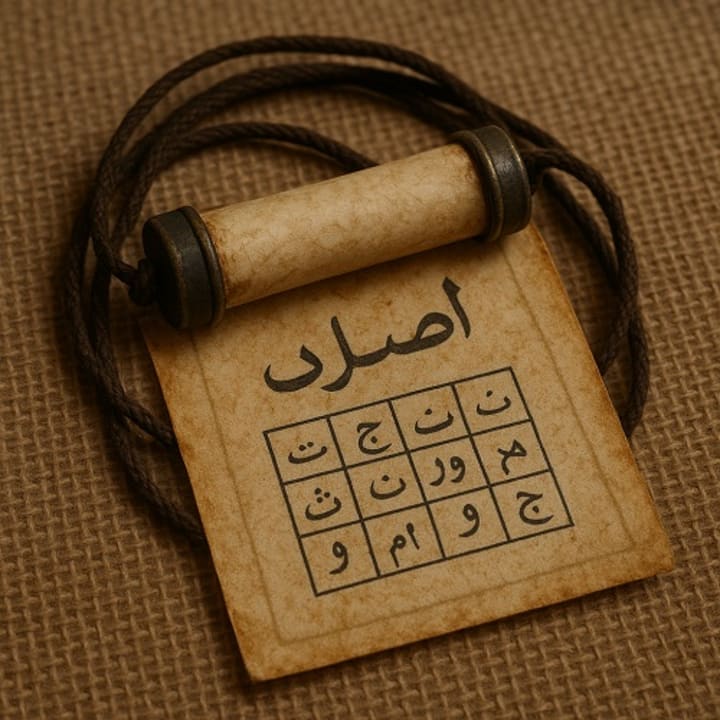

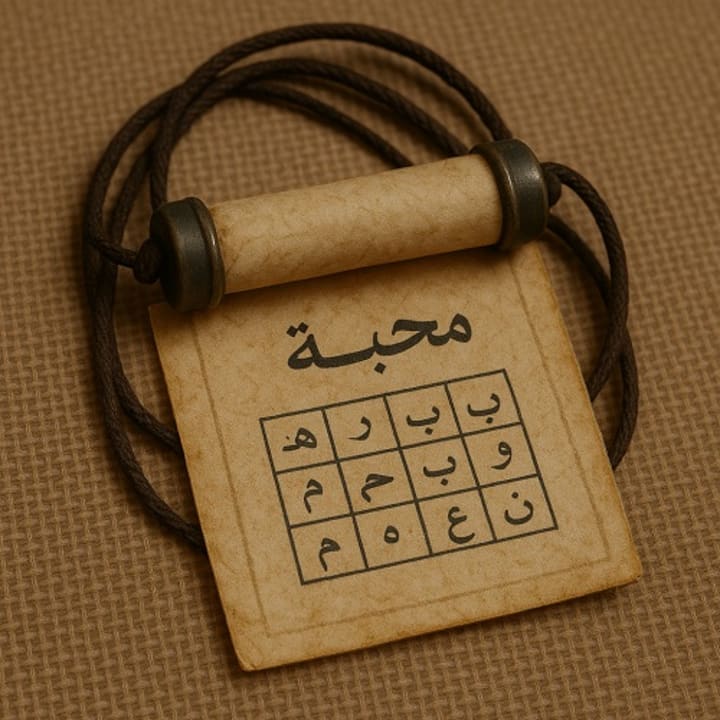

Love taweez form a distinct and socially recognizable subcategory, explicitly framed around emotional or relational goals. Practitioners differentiate between mahabba (mutual affection), bringing back or attracting a beloved and tahyij (intensifying desire). Unlike protection amulets, which use standardized Qur’anic verses, love taweez often combine Qur’anic passages with letter squares (awfaq), invocations of divine names associated with tenderness (al-Wadud, al-Latif), and personalized inscriptions referencing the names of the two individuals involved. Field reports from Moroccan universities describe that such taweez are commonly requested during periods of emotional instability like breakups, stalled engagements, or fears of romantic competition and typically involve tailored instructions for placement (e.g., under a pillow, sewn into clothing, or kept near the chest).

Social Motivations: Why Moroccans Seek Taweez for Love

Requests for love taweez in Morocco emerge from concrete social pressures rather than abstract romantic ideals. Fieldwork from Moroccan universities studying fqih and fqiya consultations shows that clients typically approach practitioners at moments of emotional instability or social vulnerability. Common motivations include delayed marriage, a concern frequently voiced in Arabic-language women’s forums, where users describe difficulty securing stable engagement prospects despite familial expectations. In urban settings such as Casablanca and Rabat, many women report anxiety over competitive dating environments shaped by economic precarity and rising marriage ages.

Another strong motivator is fear of losing a partner. Testimonies posted on platforms reveal that individuals (predominantly women) seek amulets after sudden breakups, perceived rivalries, or partner withdrawal. These requests reflect the social weight placed on continuity in relationships, as abrupt separation can carry reputational consequences for women in conservative neighborhoods.

Class mismatches also drive demand. Ethnographic reports from Fes and Tangier describe cases where relationships face parental disapproval due to differences in income, education, or regional background. Love taweez in such contexts function as tools for negotiating barriers that feel beyond personal control.

Anthropologically, these motivations align with insights from Schielke’s work on “emotional pragmatism” and Bowen’s analyses of everyday Islamic decision-making: people act not out of doctrinal rebellion but from a desire to stabilize fragile emotional situations. Love taweez become a practical avenue for individuals attempting to regain agency in environments where personal choice is constrained by family structure, gender norms, and economic realities.

Gendered Knowledge: Women as Ritual Experts

Across Morocco, knowledge related to love taweez is transmitted primarily through female ritual networks, a pattern consistently documented in ethnographic studies from universities in Rabat, Fes, and Marrakech. While male fqih practitioners dominate areas such as legalistic ruqya or Qur’anic healing, the domain of emotional and relational concerns, especially love, jealousy, and marital tension tends to fall under the expertise of women ritual specialists. These include fqiya (religiously literate women), rahmana (rural healers drawing on Amazigh traditions), and experienced older women in extended families who act as informal advisors.

Urban field reports from Fes el-Bali and Marrakech medinas note that women frequently serve as intermediaries between clients and male scribes, translating emotional problems into the coded language of amulet requests. In northern regions such as the Rif, female healers often combine Qur’anic textual elements with inherited Amazigh symbolic practices, reflecting a hybrid religious landscape documented in French- and Arabic-language anthropological literature.

Online spaces reinforce this gendered dynamic. Arabic forums where love taweez are discussed are overwhelmingly populated by women sharing experiences, troubleshooting rituals, or recommending specific practitioners. Rather than passive consumers, these women actively evaluate the credibility of healers, compare methods, and exchange practical advice.

Ritual Processes: How Love Taweez Are Actually Made

Ethnographic field reports from Moroccan universities and manuscript studies from the Bibliothèque Nationale du Royaume du Maroc describe the making of taweez as a regulated, text-based practice, shaped by local custom and Islamic symbolism rather than by improvised magic. Practitioners work within recognizable conventions that emphasize Qur’anic textuality, moral intention, and material purity.

The writing materials are consistent across the country. Many love-related taweez use saffron ink dissolved in rosewater - a method frequently mentioned in Arabic ruqya forums and supported by manuscript traditions in which saffron is considered a respectful medium for Qur’anic writing. Some practitioners use black ink for the outer inscriptions and saffron for inner, more personal lines which is an approach documented in several Fes and Tetouan field studies.

The content typically combines Qur’anic verses associated with affection, most commonly al-Ikhlaṣ, al-Falaq, and the verse on tranquility and affection from Qur’an 30:21—with structured letter squares. Manuscripts attributed to the North African transmission of al-Buni’s works show how these squares encode symbolic relationships rather than providing “magical formulas.” Names of Allah associated with tenderness and harmony, such as al-Wadud (The Most Loving) and al-Latif (The Gentle) are often placed in prominent positions.

The writing process follows socially recognized rhythms. Practitioners frequently select times considered conducive to clarity and concentration, such as early morning or Friday before noon. The taweez is then folded in standardized formats: rectangular packets sewn into small cloth pouches, leather cases worn under clothing, or paper compartments placed in personal spaces.

Circulation Networks: Where Love Taweez Are Obtained

The circulation of love taweez in Morocco follows clear social and geographic pathways documented in ethnographic surveys, market studies, and practitioner interviews. In major cities such as Fes, Marrakech, and Casablanca, clients typically obtain taweez through urban healer networks located in old medinas. Field observations from Fes el-Bali describe clusters of male fqih who specialize in written amulets, often operating from small book-lined rooms near mosques or artisan quarters. Women seeking love-related taweez frequently approach these practitioners through female intermediaries, a pattern also noted in Arabic online testimonies where users recommend “trusted middle-aged women” who “know who writes properly”.

Sufi zawiyas constitute a second channel. In regions like Tafilalt and Souss, visitors approach Sufi lodges during weekly rituals to request amulets blessed with the baraka of a particular lineage. Although these taweez are not explicitly marketed for love, many clients report requesting “affection,” “reconciliation,” or “ease in relationships” as part of personal supplication - details mentioned in French-language accounts of Sufi pilgrimage circuits.

A third circulation route is the weekly souk economy. In markets such as Souk Jema el-Fna (Marrakech), healers sell premade taweez for general attraction or harmony, packaged in small leather pouches. Prices reported in forums typically range from modest symbolic donations to more substantial payments depending on personalization and practitioner reputation.

These circulation networks reveal that love taweez move through layered economies of trust, combining formal religious authority, informal female networks, and the pragmatic marketplace.

Moral and Religious Controversies

The use of love taweez in Morocco sits at the center of a persistent moral debate shaped by competing religious interpretations. Official religious bodies—such as Dar al-Ifta al-Maghribiya and regional councils of ʿulamaʾ regularly emphasize that amulets for manipulating another person’s emotions violate principles of intention (niyya) and autonomy. Their fatwa archives include multiple rulings distinguishing between permissible Qur’anic supplications for harmony and impermissible attempts to “compel affection”. These rulings frequently cite Qur’anic verses condemning coercive sorcery (sihr) and warn that altering someone’s emotional will crosses ethical boundaries.

In contrast, many Sufi-oriented practitioners and lay believers interpret love taweez through the lens of Baraka - the channeling of divine blessing rather than force. Ethnographic observations from zawiyas in Fes, Chefchaouen, and Tafilalt document practitioners who frame their work as “material prayers,” insisting that textual amulets merely support emotional clarity or soften tension within relationships. This interpretation aligns with everyday Moroccan religiosity, where material practices coexist with orthodox doctrine.

Conclusion

Love taweez in Morocco occupy a complex space where emotional need, social pressure, and religious interpretation intersect. Far from being marginal or purely “magical” they operate as social technologies through which individuals attempt to regain stability in moments of relational uncertainty. The ethnographic material reviewed demonstrates that these amulets are used not to overpower the will of others, but to negotiate vulnerabilities rooted in class constraints, family expectations, and the unpredictable dynamics of modern relationships.

About the Creator

salam burdu

Taweez for all problems - Visit Our Website : https://furzan.com/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.