Attempting Harmony

For Shay, valuing imperfection is easier said than done.

Three sharp knocks at the front door. Not threatening but not friendly, either.

Shay was in the kitchen when she heard them. Awake for less than ten minutes, her body was still creaking as she reached up to grab her coffee mug from the cabinet and down to pull half and half from the fridge.

Shay took her time walking to the entryway, hoping the knocks were from someone who had delivered a package and promptly left; she was in no state to greet anyone or have a spontaneous encounter. Shay peered out the window and, upon seeing a threat-less porch, cracked open her front door.

To Shay's right, a package the size of a sandwich board was leaning against the wall. She maneuvered it over the threshold and closed the door, examining the parcel for any identifying marks.

Shay had spent her early 20s working at Sotheby’s, where she wore uncomfortable attire that made her look sleek, mean, and beautiful. At that time, she was a glorified receptionist for a small art appraisal department in Pasadena. She spent most of her time at work combing through an inbox full of unsolicited appraisal requests. She replied to the names that didn’t matter, often without tact, finesse, or creativity. It was a dull job.

Shay had embarked in the art world hoping to find nuanced, meaningful work. This job was neither.

Shay mostly referred to a chart and used the numbers it led her to to fill in the blanks of response template emails. When names that did matter appeared in her inbox, the emails were forward to her bosses.

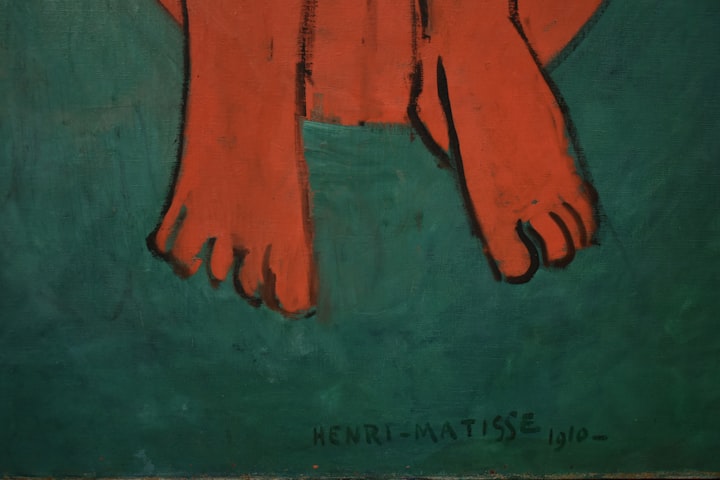

Shay ripped off the brown paper and felt a vacuum open beneath her sternum. She knew what it was immediately, but she had no idea why or how it was in front of her right now. It was a lithograph Shay had assessed herself, on a rare occasion when one boss was on maternity leave and the other was out with the flu. She remembered its details precisely, because the piece had been one of her favorites in high school: Henri Matisse, Danseuse au fauteuil en bois, from Dix Danseuses (Dancer in a Wooden Armchair, from Ten Dancers), 1925-1926.

The piece had been on loan to the Norton Simon Museum, where it graced the wall across from coat check. The print belonged to a private collector who was interested in selling. Matisse being Matisse, pricing for such a print was straightforward, and on behalf of Sotheby’s Shay valued the lithograph at $28,000.

Shay’s therapist liked to ask how old Shay felt in emotional moments. For the most part, this technique worked and was helpful, but the practice felt a little too on-the-nose for Shay. Embarrassing in its earnestness.

Annoyingly, Shay’s brain had picked up this habit and often reverted to it without Shay’s conscious consent. In this moment, Shay was 9 - almost 10 - and it was Christmas morning. Stockings ripped down and rabidly opened. Among drugstore stuffers, Shay unearthed a stack of scratchers. She squealed for a quarter and began scratching faux silver off the lotto tickets as fast as she could . Letters and numbers were lining up - $5,000, $10,000, $20,000. Shay couldn't believe it, she was going to be one of those kids on the news. She was going to have a room full of brand new Beanie Babies.

Minutes later, high on new money and performing for her brother's camcorder, her parents nudged her to read the fine print. THESE TICKETS HOLD NO CASH VALUE AND ARE MEANT FOR ENTERTAINMENT PURPOSES ONLY. Oh, the crushing humiliation of dashed hopes for a 9-almost-10-year-old.

Shay carefully lugged the piece into her living room, where she propped it against an armchair and ripped off the final third of its wrapping.

In the bottom left corner, alongside Matisse’s penciled signature, was a six-inch gash.

Shay began drafting an email to no one in her head: “Due to the evident physical damage, this piece is devalued by approximately 25%. This piece is now valued at about $20,000.” Shay then thought to herself, "What the fuck is this doing in my living room?"

Shay was 29, on the cusp of 30, and approximately $20,000 in debt. Though she knew this number was not crippling - plenty of her friends owed more for grad school - the amount had recently been feeling like an insurmountable obstacle. Probably because she had accrued it irresponsibly and without pleasure.

At 28, Shay had quit her job to take off around the world. At the time, she was relying on her trip to be an odyssey, a catalyst for monumental change. She needed this excursion to deliver, at minimum: clarity, at most: a full-fledged epiphany.

Shay had once listened to the first 24 minutes of the audiobook of Be Here Now by Ram Dass. His unhappiness had led to enlightenment; she was hoping for a similar overhaul of perception and consciousness, along with a suntan and some saucy anecdotes to tell at cocktail parties. That's a lot of pressure for a few plane tickets and hastily- booked Airbnbs.

During the first leg of her trip, Shay was hoping to fall back in love with art. She did not yet know that "wherever you go, there you are," so her cynicism and exhaustion followed her through Europe like a shadow of stale cigarette smoke.

At The Magritte Museum in Belgium, Shay stood before an informational wall and learned about the surrealist's first career in advertising. "Maybe that's what I should get into," Shay thought. Doing something blatantly commercial suddenly seemed braver than using the art world's enticing facade to feign creativity and mystery.

At the Picasso Museum in Spain, Shay grew more and more furious watching tourists revere this overrated artist whose abusive rein left suicides in its wake. Shay should have known better and skipped this museum all together, but she was growing bored of her international apathy and wanted to feel something - anything - exciting for a change.

At The Louvre in France, Shay felt depressed as shit. Mona Lisa surrounded by selfie sticks, an observation so tired she didn't even feel like tweeting it.

The only exhibit that piqued her interest at all was a temporary setup at the d’Orsay, about the history of pornography. Shay enjoyed being reminded that figures made to look stoic and romantic by the limited lens of history were just as stupid and depraved as the people she knew, as herself. It made her feel less anxious about not having accomplished anything of import in nearly three decades.

Like her peers, Shay had taken out thousands in student loans to study art history. But then she graduated and got a job at Sotheby’s, believing herself spared of the existential chaos she witnessed in her friends. Shay went to work every day wearing clothes from Nordstrom Rack, and by 26 she was in the black

But then, at 28, Shay went and had a textbook quarter-life meltdown. Pulled what her therapist would call "a geographic." To no avail.

In her free time, Shay took classes in Japanese art forms around LA. First at Pasadena City College, then at the Skirball Cultural Center when she had worked through the Eastern Arts section of PCC’s course catalogue.

The classes were originally recommended by Shay’s therapist, who thought studying things like ikebana and wabi-sabi would be beneficial for Shay’s cognition. Shay’s therapist was obsessed with Shay being a perfectionist, and thought that studying imperfection as an art form would be beneficial for her aesthete mind.

Shay’s therapist was a recommender; she recommended books, TED Talks, documentaries, and courses. Eventually, Shay’s “homework” list got so long that she bailed on therapy so she could make time to catch up. It was getting too expensive, anyway.

In one of Shay’s classes, students were assigned to keep a notebook for two weeks, in which they were to record all instances of imperfection encountered in day-to-day life. “Perfection is not interesting,” their professor liked to tell them with gravity. “It sets us up for failure, in both art and life.” This was all well and good in the abstract, but Shay was not about to take such sweeping advice from a middle-aged community college professor. Though she did agree with him that “juxtaposition is what draws the eye,” this is what the contents of their notebooks were to represent.

Though Shay knew she had a shoebox full of mostly-empty notebooks at home, she decided to treat herself for the sake of the assignment and beelined to the nearest bookstore. Shay could never deny the allure of a papery fresh start, and she selected a small black notebook from a revolving wire rack near the checkout chapter.

Lying in bed at night, thinking through and planning the next day, Shay often pictured herself in a lucite hallway. Above her was an identical passage, the floor of which was her ceiling. Overhead existed an elevated version of herself - she could see it so clearly, bathed in flattering white light. Shay felt like her entire life was spent trying to crack open this perfect version … she was desperate to reach it so she could finally exhale.

Only then, could she even consider applying this “beauty in imperfection” business that people kept hounding her about to her own life.

At Sotheby's, the department that had intrigued Shay most was Reproductions. “Repros,” as it was known in the office - a team of one administrator, one head, and two freelance artists who arranged and executed picture-perfect plagiarized pieces for wealthy clients who wanted to display the art on the walls of their home while simultaneously keeping the valuable original pristine, in a high-security, temperature-controlled, art-specific storage facility. (Of course, the p-word was never, ever, thrown around in the office.)

These commissioned reproductions enthralled Shay. They simultaneously disgusted and captivated her; though she abhorred plagiarism in principal, she knew that if she had the money she would never risk letting a masterpiece soil devalue on her walls.

Shay had a bit of a magnetic thing with one of the repro artists, Max. Everyone in the office knew that he adored Shay, in a way that made her stall out second guessing herself when she thought about it head-on. His adoration felt unwarranted, and his kindness often made her want to block his number.

Shay and Max had hooked up twice - once at the holiday party, and again a few weeks later; a spot of carnal comfort amidst the post-holiday hangover of a month January. But then he asked her 0n a proper date, and she shut down. She wasn’t ready to be seen yet, especially with Max. She wasn’t ready to exist in the world in any certain or permanent way

Late morning light spilled into Shay's living room, illuminating the the piece before her. The $20,000 piece. The original Matisse print. The lithograph signed by one of history's most famous artists.

Shay's mug of coffee sat cold before her. Her phone buzzed, it was a text from Max: Shay - long story, but this is my gift to you. You know as well as I what it’s worth (gash and all), but I dare you to hang this on your wall and enjoy its value every day.

Years ago, in a moment of mortifying sincerity, Shay had been moved to tears telling Max about Matisse's Dancers. Three glasses of wine and she was blubbering in a restaurant booth. Shay had first seen Danseuse au fauteuil en bois in ninth grade, and could not believe an artist would ever find a soft-bodied ballerina worth portraying. She thought about those dancers a lot.

Shay got up to go look under her kitchen sink, where she hoped to find a hammer and a nail.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.