(1) Seeing the System Clearly

Why So Many People Feel the Effects but Cannot See the Cause

- The Shared Feeling No One Can Quite Explain -

Most people do not need to be convinced that something is wrong. They feel it in rising costs that never seem to stabilize, in rules that change without explanation, in institutions that demand compliance but no longer command trust, and in a political process that feels permanently hostile yet strangely ineffective. These experiences are not isolated. They are widespread, persistent, and remarkably consistent across demographics, ideologies, and personal circumstances. What differs is not the feeling, but the explanation people are given for it.

Some are told the problem is moral decay. Others are told it is the wrong party, the wrong leader, the wrong voters, or the wrong culture. Many internalize it as personal failure, believing they simply did not work hard enough, plan well enough, or adapt quickly enough. What almost no one is given is a coherent structural explanation that connects these experiences into a single, intelligible system. This absence of synthesis is not accidental, and it is the primary reason people feel stuck.

This essay is not about blame, outrage, or persuasion. It is about diagnosis. Before anything can be fixed, it must first be understood. And before it can be understood, the system producing these outcomes must be made visible.

- The Difference Between Experiencing Harm and Understanding Cause -

Human beings are exceptionally good at recognizing when something is affecting their lives negatively. They know when effort no longer leads to stability, when compliance no longer earns security, and when participation no longer results in representation. These are experiential truths, not ideological positions. People live them long before they articulate them.

What people struggle with is causality. Modern life fragments experience into isolated domains. Economics feels separate from politics. Politics feels separate from law. Law feels separate from enforcement. Enforcement feels separate from power. Each domain is discussed in isolation, often by specialists who have no incentive to integrate the whole. As a result, people experience downstream effects without ever seeing the upstream mechanisms that generate them.

This fragmentation creates confusion rather than ignorance. People sense patterns but are told those patterns are coincidences. They recognize repetition but are assured each failure is unique. Over time, this disconnect between lived reality and official explanation erodes trust, not because people reject complexity, but because they are denied coherence.

- Why Systems Must Be Diagnosed, Not Moralized -

Most political and cultural discourse today treats outcomes as moral contests. If something fails, someone must be evil, ignorant, or malicious. If harm occurs, someone must have intended it. This framing is emotionally satisfying, but analytically useless. Systems do not require bad people to produce bad outcomes. They only require misaligned incentives, unequal enforcement, and decoupled consequences.

A system should be evaluated by what it reliably produces, not by what its designers claim to intend. If a structure consistently concentrates power, shields decision makers from consequences, and distributes costs downward, then those outcomes are not accidents. They are the logical result of the design. Moral language does not change this reality. In fact, it often obscures it by redirecting attention away from structure and toward personality.

This is why diagnosing the system matters more than condemning individuals. Individuals change. Structures persist. A system that produces harm under one set of leaders will produce harm under another if its incentives remain intact. Understanding this is not cynical. It is necessary.

- How Power, Law, and Enforcement Interlock -

At the core of every functioning society is an unavoidable fact. Law is only meaningful if it is enforced, and enforcement is only credible if it is applied equally. When enforcement becomes selective, law stops being a shared boundary and becomes a tool of management.

Power enters the picture when those who influence law are insulated from its enforcement. Once decision makers are no longer subject to the consequences of their decisions, incentives invert. Policies that generate short term benefit and long term harm become attractive. Responsibility diffuses. Accountability delays. Costs are externalized. Over time, this produces a ruling class that does not necessarily conspire, but does consistently benefit.

This interlocking relationship between law, enforcement, and power explains why outcomes remain stable even as rhetoric changes. Elections alter personnel, not structure. Promises shift, but incentives remain. Without addressing how power is constrained and how consequences are applied, reform becomes symbolic rather than substantive.

- Why People Feel Paralyzed Instead of Motivated -

When people cannot see cause, they cannot see agency. They sense that personal effort is insufficient, but collective action feels captured or performative. Voting feels mandatory but inconsequential. Protest feels expressive but ineffective. Withdrawal feels safer but hollow. This produces a unique kind of paralysis, one rooted not in apathy, but in uncertainty.

People are not refusing to act because they do not care. They are hesitating because they cannot tell which actions matter and which are merely absorbed by the system. In the absence of a causal map, energy is wasted on symptoms, outrage cycles repeat, and exhaustion sets in. This is not a failure of will. It is a failure of explanation.

A coherent worldview does not promise easy solutions. It restores orientation. It helps people distinguish between leverage and theater, between structural reform and symbolic change, and between responsibility that belongs to them and responsibility that does not.

- What Is Actually at Stake -

What is at stake is not partisan victory or ideological dominance. It is whether effort remains meaningful, whether law remains reciprocal, and whether cooperation remains rational. Societies do not collapse because people disagree. They collapse when systems consistently reward behavior that undermines trust and punish behavior that attempts to restore it.

Getting the diagnosis wrong guarantees repeated failure. Treating structural problems as moral disputes leads to endless conflict without resolution. Treating systemic incentives as personality flaws leads to leader swapping without change. Only when the system itself is made visible can intelligent reform even begin to be discussed.

This work exists to make that system legible. Not to inflame, not to recruit, and not to absolve. It exists to connect what people feel with why they feel it, and to show how seemingly separate failures are, in fact, expressions of the same underlying design.

- Clarity Before Cure -

Most people are not confused because they lack intelligence or concern. They are confused because the explanations offered to them are fragmented, moralized, or incomplete. They are given stories when they need structure, and outrage when they need understanding.

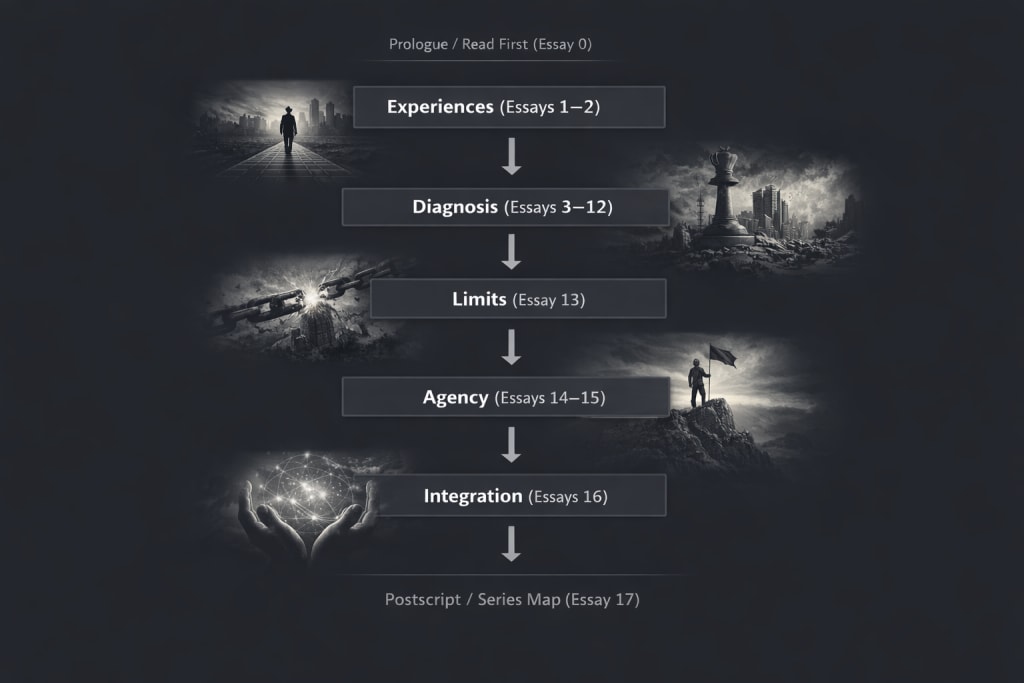

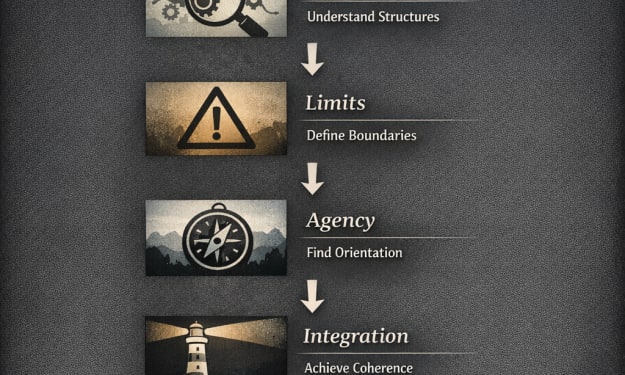

This essay is the first step in a larger project. Its purpose is simple. To slow the conversation down, pull it out of reaction, and reorient it toward cause. Everything that follows will build on this foundation. Because before anyone can decide what to do, they must first be able to see what is actually happening.

And once they do, much of what felt personal, isolating, or inexplicable begins to make sense.

About the Creator

Peter Thwing - Host of the FST Podcast

Peter unites intellect, wisdom, curiosity, and empathy —

Writing at the crossroads of faith, philosophy, and freedom —

Confronting confusion with clarity —

Guiding readers toward courage, conviction, and renewal —

With love, grace, and truth.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.