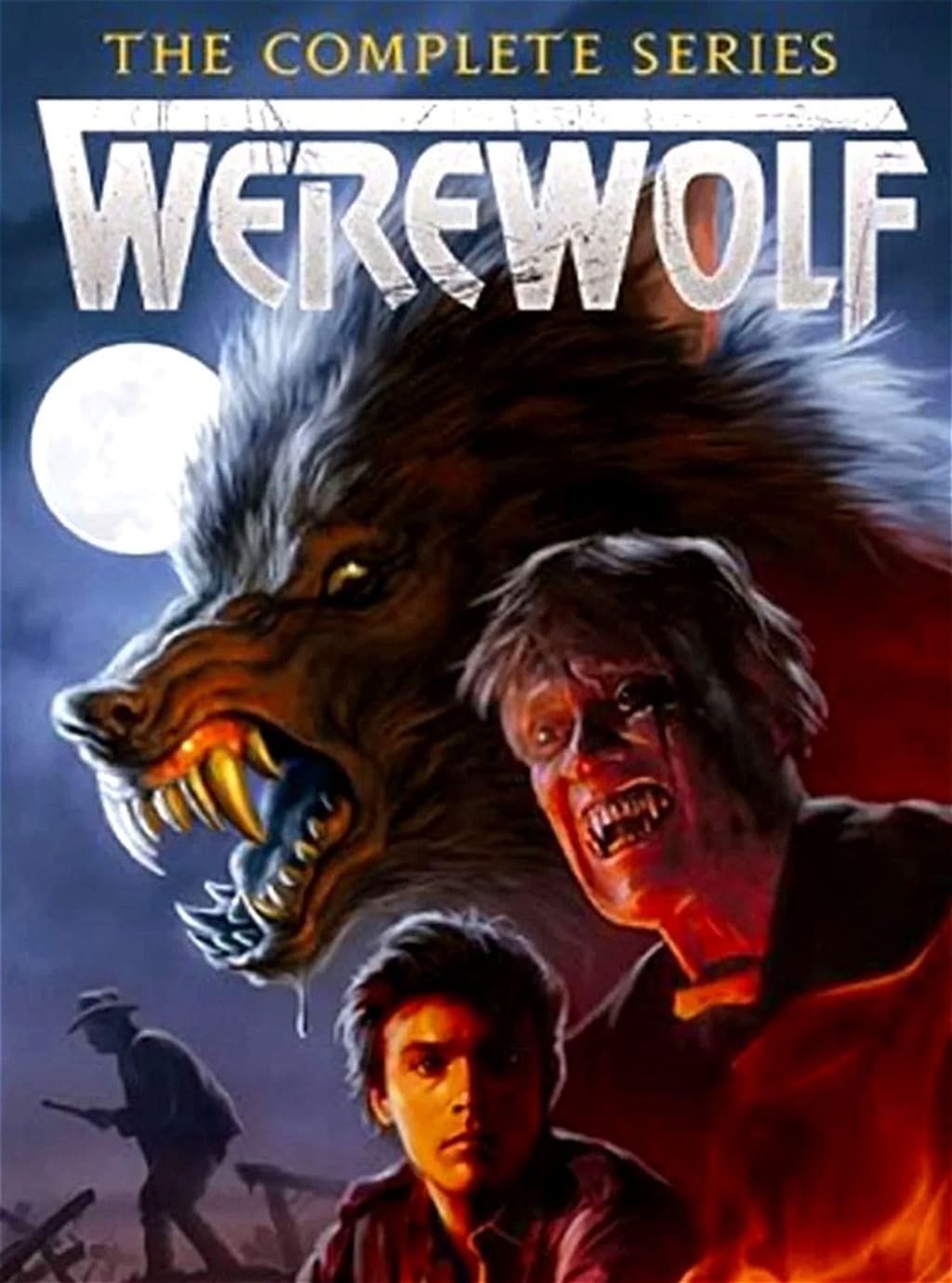

Werewolf: The Tragic Journey of Eric Cord

The Quintessential Werewolf TV Show

One of the greatest forgotten horror gems of 1980s television is Werewolf, starring Chuck Connors and John J. York. York plays Eric Cord, the wandering Bruce Banner of lycanthropy, who, episode by episode, drifts through towns full of hostile yokels and shady characters, inevitably finding himself backed into a corner. It usually takes about fifteen minutes before Eric's predicament forces the beast within to emerge. The next fifteen minutes are spent on his struggle to regain control, with his transformation from man to monster central to both his survival and the series' ongoing narrative.

Chuck Connors, playing the eyepatch-wearing Skorzeny (a name borrowed from a Nazi general), serves as the driving force behind Eric’s journey. Skorzeny is the progenitor of Eric’s curse—kill him, and Eric will be free. But the pursuit of that goal is anything but simple. Lance LeGault’s “Alamo Joe” is a bounty hunter, supposedly from Brooklyn but inexplicably sporting a cowboy hat and Texas accent. After the pilot episode, Joe’s origins are never mentioned again. Likewise, Eric’s girlfriend from the first episode vanishes without explanation.

Werewolf 1987 Episodes 1-14

So, Eric chases Skorzeny, Alamo Joe chases Eric, and along the way, our reluctant werewolf encounters abusive boyfriends, ex-prize fighters (played by Twin Peaks' Everett McGill), skeptical professors, thugs, hoodlums, rednecks—you name it. He even faces off against punks in an abandoned shopping mall.

The standout episode, in this author’s opinion, is "Nightmare at the Braine Hotel" (Season 1, Episode 16). It features Richard Lynch as a revenant wolfman with an octopus tattoo on his scalp, adding layers to the show's mythology with hints of an ancient past tied to medieval France. The episode blurs the line between reality and dream, plunging the viewer into a world where shifting perspectives mirror the uncertainty of Eric’s transformation. The decrepit flophouse setting feels like an extension of the subconscious—a dark, forgotten corner of the mind where the beast, that slavering, and hideous thing of superhuman size and strength, lurks. Lynch’s tattoo, depicting a tentacled horror stretched across his bald head, serves as a striking visual metaphor for the insidious nature of Eric’s curse.

Another unforgettable episode, "The Black Ship," plays on the horror trope of external settings mirroring inner turmoil. Eric arrives at a grimy waterfront, possibly in New England, searching for Skorzeny. A grotesque barkeep (Claude Earl Jones) sets the tone before Eric meets Otto Renfield (Steven Gierasch), a mad old man missing a leg—an eerie symbol of a life eroded by servitude to the lurking beast. Renfield lures Eric aboard a rusted, derelict boat, promising information, but the ship is a trap, a liminal space neither here nor there, a vessel incapable of motion, much like Eric’s stalled pursuit of freedom.

Locked behind iron bars, Eric faces his predicament: will he let the beast within claim dominance to escape, or remain imprisoned, a prisoner to both his human restraint and his inner monster? The answer is inevitable (the series continued for twenty episodes), but the execution is masterful. This episode also features one of the most disturbing man-to-monster transformations in TV horror history—Skorzeny, with a grotesque grin, places his fingers in the corners of his mouth and... rips. Once seen, never forgotten.

Of course, Eric escapes, waking up naked in a new town, echoing Page Fletcher in The Hitchhiker—a lone drifter on an endless, lonely road. Later episodes tackle themes of consumerism and the spiritual emptiness of Reagan-era America. In "A Material Girl" (Season 2, Episode 16), a Madonna-like werewolf (Lisanne Falk) squats in the remains of a shopping mall, a relic of American capitalism that, nearly forty years later, mirrors the abandoned husks of real malls left to rot in the wake of the internet age. Beneath her glamorous veneer lies the hideous Beast Within—yet another exploration of Werewolf’s central theme.

Unfortunately, the final episode is a letdown, with Eric confronting the cruel caretakers of an abusive nursing home—a weak conclusion to an otherwise stellar series. However, it maintains the recurring motif of Eric as an avenger of the marginalized, from drifters and punks to the elderly, a protector against unseen evils lurking in the shadows of everyday life.

Werewolf had a dark, brooding atmosphere, theatrical transformations, and a haunting score that set the stage for later genre-defining shows like Twin Peaks and The X-Files. Its blend of horror, existential dread, and slow-burn suspense made it a standout among its contemporaries—Monsters, Tales from the Darkside, Tales from the Crypt, Ray Bradbury Theater, Friday the 13th: The Series, Max Headroom, and The Hitchhiker.

Few shows of the era captured the horror of the Beast Within quite like Werewolf. It reflected the primal fears lurking beneath the glossy exterior of 1980s America, proving that even the most all-American heartthrob could be one bad moment away from revealing the monster inside.

Werewolf 1987 Episodes 15-29

Connect with me on Facebook

My book: Cult Films and Midnight Movies; From High Art to Low Trash Volume 1.

Print:

Ebook

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments (1)

Sounds like a lot of fun for which I'm not sure I'll find the time. I remember it from my early twenties but never watched it. Another enticing review, Tom.