I just finished watching, for what seems to be the hundredth time in my life, the 1974 grind house mega-classic, the horrific blockbuster, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, a film that has achieved a legendary cult status. It is a stark, ugly, brutal film, calling to mind that other film of the era with which it shares the most infamy--Wes Craven's social shocker cum medieval morality play Last House on the Left (1973). Both films seem, by the standard of mere "entertainment," to be grueling, morbid experiences, films calculated to bring about the most dire feelings of revulsion, if not titillation, on the part of eager but undeniably guilty viewers; morally guilty for indulging such "entertainment", but, with that same sense of morbid wonder at the graphic display of violence, sadism, mutilation and morally repugnant acts offered by each respective film. Last House is the kinkier, most sexual, most "human" and rational, if utterly grotesque and macabre, of the duo. Texas Chainsaw Massacre is, by contrast, like sticking the viewer's head in the mouth of a particularly grisly and mutated feral animal, a vomitus descent from an "idyllic summer afternoon drive" (as described by opening narrator John Larroquette) into what, indeed, is the depths of an actual cinematic nightmare; albeit, one that is based upon the real-life doings of such individuals as Ed Gein and the medieval Scottish "monster brood" known to history as the "Sawney Beane" clan. (The last inspired, incidentally, Wes Craven to later go on and make The Hills Have Eyes (1977), exploring similar themes as Texas Chainsaw.)

The film begins with an obese, unlikable, wheelchair-bound man urinating after the van he's in has pulled over to the side of the road. This is Franklin (the late Paul A. Partain), and an exhaust blast from a passing semi truck sends him rolling down the embankment. Next, we see him in a van with four good-looking, utterly "normal" teens of the era: Sally, his sister (the late actress Marilyn Burns, who was also famously in 1976's TV adaptation of the Manson killings, Helter Skelter), Jerry (Allen Danziger), Kirk (William Vail), and Pam (Terry McMinn); the latter seems the most stereotypical "Texan' for her film role.

We get the idea Franklin has been allowed to come along as a favor, or as a demand from Sally's parents; perhaps that they should "include" the disabled brother, in an era before the handicapped were often treated with a lot of consideration. It is an era of Vietnam, of course, of student turmoil, racial strife, sexual and drug excess and experimentation; and, interestingly enough, experimentation with the occult. The latter of which, in the form of an astrological subtext, will play an important role in the spirit of what is to follow.

Why they are driving and where to is, at first, rather a mystery. There is a certain lonely, doomed, "outing in Hell" (or even the weird, detached, Twilight Zone-type feeling) to their excursion. No one looks as if they are aware of, precisely, why they have come; no one looks as if they are enjoying things, or having a very good time. Franklin complains of the heat.

The sky is vast and blue, photographed above, looking as if it is baking the hot desolate highway. Pam reads from an astrology book, a forecast that "Saturn is malefic...is in retrograde. That means its malefice is increased." Beforehand, we have been treated, during the opening titles, to images of the sun and solar flares.

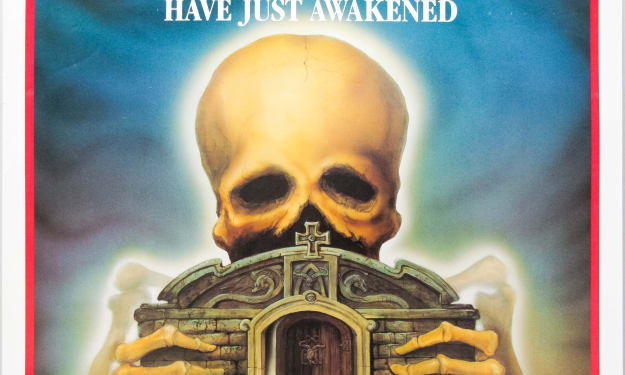

(The grim opener is a pull-away shot of a grisly, decomposing skull, wired atop a stone monument, in an awkward position, as if the corpse were thrusting its pelvis into the marble--or crawing up it as one crawl up a laddeer, to escape the grave. This has come after opening shots, complete with what sounds to be the high, unnerving grinding of metal and a radio news bulletin reporting grave robbing, has shown us flashbulb images of what seems to be decomposing hands and other extremities.)

Jerry asks Kirk if he "believes the stuff his old lady is hawking me?" And then comes The Hitchhiker.

"My Family's Always Been in Meat!"

Franklin's quiet observation that "I think we just picked up Dracula..." is borne out by the weird, vagrant-like character played by actor Edwin Neal, the famous "Hitchhiker," whose wine-colored stain upon his face may be a birth mark; or, alternately, some type of primitive face paint.

His puce green army shirt suggests almost a veteran of the era's Vietnam conflict; however, there's a strange, pagan-like pouch hanging from a thong around his neck, and his long greasy locks, impaired, stuttering, halting speech, and screwed-up, dirty expression marks him as a mental case.

He explains he's "been at the slaughterhouse," and that his family's "always been in meat." His "daddy worked there," and his grandfather, too. In a foreshadowing of what is to come, Franklin mumbles to his friends that this man must be from a "whole family of Dracula's."

The following conversation proceeds between the two most backward and socially-impaired of the riders in the van:

Franklin : Hey man, you ever go in that slaughter room or whatever they call it? The place where they shoot cattle in the head with that big air gun?

Hitchhiker : Oh, that gun's no good.

Franklin : I was in there once with my uncle.

Hitchhiker : The old way... with a sledge! You see, that way's better. They die better that way.

Franklin : Well, how come? I thought the gun was better.

Hitchhiker : Oh, no. With the new way... people were put out of jobs.

Franklin : Did you do that?

Hitchhiker : [digs through pouch for a few pictures] Look!

[hands them to Franklin]

Hitchhiker : I was the killer!

Franklin : [looking at the pictures] Damn...

Right away, we have one of the subtexts that will haunt the rest of the film in subtle, albeit noticeable ways upon repeat viewing: the idea that industrialization leads to decline, that the economic and cultural bounty of the past has been subverted, allowed to decay, and so, by extension, anyone that was left in the dust by those changes, will be altered, too; and for the worse. Family life, of course, once decent, traditional, and prosperous, centered around an industry such as the slaughtering of cattle, might, in the sense of something out of H.P. Lovecraft, begin to decline and deteriorate; a cancer of familial degeneration and decay.

(And the theme of mutation and madness, perhaps brought about by incest, is not far off from that.)

The Hitchhiker is carrying around photographs of slaughtered cattle. Ordinarily, this would be enough to shock the rest of the passengers into defensively ejecting him. But what he does next is even worse than that. Grabbing Franklin's pocket knife, he exultantly slashes the palm of his hand, letting the blood flow down his wrist, while the shocked onlookers yell out. He then reaches into his boot and pulls out his own menacing straight razor. "I have this knife!" he taunts the other passengers. "It's a good knife!"

He then takes the ancient Polaroid camera he has been carrying all along, and takes Franklin's picture. There is a double meaning here, insomuch that, in primitive belief, the picture may "steal the soul." He gives the photo to Franklin, who complains that "It didn't turn out so good," before the Hitchhiker demands payment for his service. Kirk tells Franklin to give the Hitcher back the picture; after which, the child-like psychotic seems curiously offended.

He takes the photo, puts it on a piece of aluminum, and covers it with some sort of flammable powder or chemical agent. This unleashes a curious blast of air; he then reaches over with the straight razor and slashes Franklin's arm. The rest of the passengers erupt, finally forcibly ejecting the Hitchhiker as they slow, and he chases the van, kicking it...and somehow marking it with a strange, dripping red symbol. (Is it blood, or paint?)

It is as if he has completed three separate acts of a curse. This indeed, seems to finish the first act of the film.

"I Got Some Barbecue!"

The teens quickly recover (although, why, at this point, they don't just decide to head home is a mystery. The weird, doomed, dream-like quality of this "fun trip" lends it an even more foreboding quality), and stop for gas at a little out-of-the-way filling station, wherein the truculent owner, the late actor Jim Siedow, (and another man that could be mistaken for a Vietnam veteran of the period), wash the van's windows. Siedow informs the teens he "has no gas. Tank's empty. Transport won't be around till late this afternoon."

(The man washing the windows, the "veteran," has first been seen to be staring up at what appears to be the sun through drifting smoke. Another shade of meaning, perhaps, giving the cruel, stark and brutal events below a greater context. In point of fact, one of the frequently employed techniques here seems to be a sort of "worm's eye view," wherein the shot is angled upward from the ground below, to make the actors appear gigantic. The obsession is on the comely bodies of the desirable actresses, of course; but, the sort of "boxed angle" camerawork [i.e., rendering just the head and arms, or a section of same], is employed also in the short scene wherein the kids stop to make sure the spate of grave robbing being perpetrated across East Texas has not been done to their grandparents' graves. An ancient drunken man is shown, lying on the ground, holding a bottle; from this vantage point, he is simply a head and arms and part of a torso. He complains that they "laugh at an old man," but that, "them that laughs, knows better." He serves the purpose, in this early scene, as a sort of "ancient mariner"; or a guidepost, warning of the descent into Hell that is to come.)

After being warned by the old man to stay "away from old houses," (we finally learn they are going to the Franklin family's abandoned Texas farmhouse), they buy some "barbecue," and head on their way. Finally making it to the place, they realize they have a terrible problem ahead of them with getting enough gas for the return trip, but head into the house anyway, laughing and giggling and stomping about the ruins as if they are high. The house has been baking like a derelict, peeling and deteriorating like the lonely remains of the dead, amidst tall weeds and prickly brush, for years it seems.

Sally takes her friends on what was once a tour of her room as a child. She is apparently eager to show off, exclaiming about her childhood fascination with zebras, whilst the bitter, unlovable Franklin rolls around downstairs in his wheel chair.

Giving a "Bronx Cheer" to the young and sexy and joyous people above, he exclaims, mockingly, "C'mon Franklin, it's going to be a fun trip. Well, If I have any more fun, I don't think I'm gonna be able to take it!" He then spies a curious thing that looks like a piece of bone, hanging from a string in the archway of a door.

Girl on a Meat Hook

Pam and Kirk go out to the "swimming hole" (presumably to do a little more than just skinny dip), and find that it is, unfortunately, completely dry. Hearing the workings of a generator, Kirk and an increasingly nervous Pam walk across a field to the neighboring house, which has a run-to-riot yard and weird assortments of tin cans and other detritus tied to barren, sun-bleached branches. Pam sits on a nearby wooden swing, and Kirk goes inside the house to see if he can trade his guitar and a few bucks for some gas by the presumable occupants.

Going inside, he spies beyond a long hall by the staircase, highly polished, and walls of peeling paper. Beyond this, the doorway opens onto a red wall filled with what appear to be...hunting trophies. He hears something, moves forward, seems to trip as he enters the door.

It is then we are introduced to the horror beyond. Leatherface, the iconic monstrous splatter-movie ogre, comes charging out, erupting full-blown from the recesses of our subconscious collective nightmare of the bestial, the grotesque (because degenerate and gone back to a semi-human state).

Leatherface, so named because of the ragged, gruesome mask of tanned human flesh he covers his face with, is a semi-retarded, subhuman monster from a fairy tale, perhaps; inspired by Wisconsin grave robber and necrophiliac ghoul Ed Gein (who kept human flesh face masks in furtherance of his goal of sewing together a full-body "woman suit" from pieces of cadavers he rifled from Plainfield Cemetery), Leatherface, in contrast to Gein, who was at least verbal, cannot speak in any coherent manner. He seems to, instead, emit a sickening, pig-like squeal, and a gobbling and clucking worthy of a turkey or chicken. His dress is de riguer for Texas "Good 'Ol Boys": a short-sleeved button-up shirt, and a tie. Over this, an apron bespeaks the fact that he is laboring at the preparation of...food.

Kirk is dispatched with one blow of a huge hammer (no one being "put out of a job" here), and, after having what appears to be a seizure on the floor, is dragged back by Leatherface to be exsanguinated, dismembered, and turned into barbecue.

End of Kirk.

Pam, exhausted at waiting for Kirk, (who is next seen in a wonderful shot from the back of her thighs, up the swell of her butt, and commencing up her long sleek waist and back), walks up to the porch slowly. Coming up to the front door, she is shocked to see what appears to be a human tooth come tumbling out after she knocks. She goes inside, finds the infamous back room immediately.

What follows is one of the most chilling of all scenes in the picture. Pam slips in the blood on the floor, falling face first into a room that is like the psychological outgrowth of some primitive, surreal fantasy of slaughter: the floor is littered with fragments of bone, a live chicken clucking in a cage that is far too small for it. It is hanging suspended, like tortoise shells, finger bones, horns and other macabre relics, from strings on the ceiling. There is what appears to be a macabre, primitive altar made of human and animal skulls, draped with tanned hide. The entire place seems a charnal torture chamber of feathers and bleached skeletal remains, the workroom of some psychopathic supplicant in the Temple of Butchery.

Then the gabbling, mewling hideous satire on man, Leatherface, chases her back out the front door, capturing her like a child in his massive arms, before hauling her back inside and placing her rather indelicately on a literal meat hook. She hangs suspended for a few moments, reaching in vain behind her to try and free herself from being pinned to death, like an oversized insect.

End of Pam.

The afro-sporting Jerry is next. He goes over to look for the other two, finds the lonely farmhouse of the damned, and proceeds inside to investigate. Going into the "Meat Hook Room," he sees the locked freezer. Hearing something from within, he opens the top. Pam rests within, the musique concrete soundtrack suddenly squealing and grinding as her eyes pop open and she, zombie-like, (perhaps because of the muscle reaction of dying nerves), shoots upward in a frightening jump. (It is as if she has some ghastly, spring-like mechanism inside her; bringing to mind the spring-driven cadaver in Poe's classic tale, Thou Art the Man.)

Leatherface emerges once more.

End of Jerry.

The soundtrack continus to rattle on, with audio slices and rumbles and grinds, like a rusted machine. Leatherface sits, staring from the window in contemplation. We note he, unsurprisingly, has bad teeth.

End of Act 2.

"Look What Your Brother Did to the Door!"

Marking out Act 3 of Texas Chainsaw Massacre is, tellingly, a shot of the full moon; keeping, of course, with the quietly implied astrological subtext that has already marked the movie since the opening. Franklin and Sally are panicked now, Jerry, Kirk and Pam seemingly having vanished. They wander around the van, yelling in futility into the darkness for their friends.

Seen only in the van's headlights, their increasing desperation can be felt. With no reply to their constant yelling, Sally and Franklin argue over the flashlight, Sally wanting to go off and look for them, and Franklin realizing that they weren't even left the keys to the van; there is no leaving this place. Finally, Sally complaining that she can't push Franklin's wheelchair "down that hill," she does so anyway, Franklin holding the flashlight, and both of them calling out for their vanished friends. Finally, deep in the woods, Franklin says he hears something. "Sally, wait!"

Leatherface appears in the flashlight glow, hefting his ever-ready saw, and ...sawing Franklin in half as he sits in his chair.

End of Franklin.

What follows is Sally being chased, running and tripping and screaming, through the dark trees, across, overgrown paths, bloodied and in a state of sheer terror, with Leatherface always hot on her heels (though why he never manages to catch her makes it seem, almost, as if he is just toying, cat-like, with his prey).

She makes her way to the shockingly, brightly-lit murder house. Charging upstairs, she finds, to her amazement and horror, one cadaverous old man, and the literal corpse of an old woman, sat, side-by-side in a sickening tableaux. Cobwebs seem to have grown between the decaying duo, and, Sally can no longer approximate any of what she has seen tonight with anything she has experienced before. What is going on here? It is baffling and surreal. The dead and decrepit given prominence; ressurected, as it were, in a place and on a night that reveals the world to be one wherein madness and death lie, exalted, beneath a gibbous moon.

Hearing Leatherface on the stairs, she jumps from a second-story window. How it is she manages to still be moving after this is a mystery, but she then makes her miraculous way to the little gas station, whose owner, actor Jim Siedow, "has no gas." She goes inside, collapses on the floor, and the old man tries to, seemingly, calm her down. Leaving for a moment, while she sits there eyeing the glass counter with barbecue suspended from forks, she realizes instinctively, suddenly, that something here is also wrong. Siedow returns, begins to hit her with a broom handle, and puts a sack over her head. The audience then realizes that he was, from th ebeginning, "one of them."

Spiriting her out to his truck, he torments her with the broom handle, poking her and prodding her sadistically, while smiling a malicious grin, and bizarrely trying to reassure her (this weird, conflicting dichotomy seems to be apart of his character, perhaps because, unlike the other two killers, he spends a part of his life disguised among "normal" society).

Driving up to the house, he sees the Hitchhiker at the side of the road, holding up a piece of roadkill, his arms raised in the air, again exultantly. He beats him viciously with the broom handle, complaining he "almost got caught," and that he warned the Hitchhiker to "stay away from that graveyard!" The Hitchhiker grovels, like a wretched, semi-human creature, perhaps a stand-in for Gollum, during the beating.

They proceed to the house, where Sally is hustled in, a rag tied in her mouth with a piece of rope, and Siedow erupts in fury because of "what your brother did to the door!" (Leatherface sawed lines in it chasing his victim.)

The Hitchhiker seems oblivious to this, poking Sally in the mouth with his forefinger, and mockingly saying to her her, "I thought you was in a hurry!" (One can't help, at this stage of the picture, to see the trio of macabre ghouls as a sort-of parody on the Three Stooges, with Siedow taking the place of a very degenerate and psychotically sick Moe Howard. He yells and screams curses at the other two, although if they are brothers, cousins, nephews, it is never made quite clear.)

"Hey Granpa, We Gonna Let You Have This One!"

Sally wakes up at a dinner table in Hell, her arms tied to the arms (in the literal and figurative sense) of a chair that has been fortified with the remains of murdered and exhumed humans--presumably some of her friends. The family (we learn in subsequent films that their last name is "Sawyer. " Get it?), begin immediately to howl and laugh at her awakening. Leatherface is dressed in a shabby, too-small suit, sporting a "pretty woman" mask now, a tanned human skin mask with blush and blue coloring around the eyes. (Shades, again, of Ed Gein, whose "face mask" collection were comprised exclusively of the skin of exhumed female cadavers.)

Sally begs them to stop. The Hitchhiker mocks her. She is taunted. The stark wooden table is festooned with the remains of what appears to be rotted meat and sickening stuff. A light hangs above; amidst its glow, can be seen the contours of a human face, like a shrunken head. (Actor Edwin Neal has stated in an interview that the smell reeking from the location as they were filming this scene, with the rotting meat, was beyond sickening.)

Siedow and the Hitchhiker argue over "torturing the poor girl," Siedow being, bizarrely, against what he perceives to be cruelty or sadism in excess; and Neal's character finally rebuffs him, telling him, "You're just a cook, and me and him do all the work!"

Then comes the most puzzling occurrence, the literal "climax" of the picture, if you will. The Hitchhiker says, "I been thinking of letting Grandpa have a whack...you always said he was the best!"

Neal stands and points one long, bony arm at Sally. Siedow agrees, "Yep. Grandpa is the best killer that ever was," referring to their family occupation at slaughtering cattle. Further commenting that Grandpa could have killed more "if the hook-and-pull gang had gotten the beaves out of the way fast enough!", Neal/Hitchhiker finally stands and exclaims, "Hey Grandpa, we gonna let you have this one!"

The soundtrack instantly rumbles upward loudly, and there are quick montage cuts of Sally's bulging, terror-stricken eyes and tormented face at the suggestion; which is puzzling, in that we aren't sure exactly why the phrase should elicit more terror than anything else that has occurred. Granpa (who has previously, in his vampire-like way, been offered the blood from Sally's cut finger to suck on) is wheeled over. A hammer is placed in his hand, and a bucket under Sally's head, as Siedow, Hitchiker, and Leatherface delight in the fun pastime of "Hit the Girl on the Skull and Brain Her." Grandpa, so aged and withered he is veritably dead himself, keeps dropping the hammer. In a moment of distraction, Sally frees herself, and jumps from yet another window. (Note: Is it possible the phrase, "Hey Granpa, we gonna let you have this one?" refers, in some oblique way to a sexual act. perhaps symbolically incestuous?; but, at the very least, a sort of double-entendre hinting at the past consuming the future int he form of the rape of youth?)

The Texas Terror Two-Step

Completely driven insane by the mad torture and hideous sights she has endured, Sally lands on the hard-baked Texas sol below, the camera sweeping her blood-streaked face as she screams in frenzy, casting her gaze about like a wild animal; or the escapee, perhaps, from a lunatic asylum.

Covered in blood, she races away, the Hitchhiker and Leatherface close at her heels. She makes it to the road, the Hitchhiker following (again, cat-and-mouse-like) at her hills, "snipping at her," swiping with his straight razor. Unfortunately for him, he is not looking as he makes his way out to the road, and is crushed under the wheels of a huge eighteen-wheeler driven by an obese black man. Leatherface is still in pursuit, as well, and the driver, Sally and he all have a chase around the truck before, for some reason, abandoning it. Sally runs ahead; the truck driver turns and throwas a wrench or some other object at Leatherface, causing him to fall with his chainsaw coming to rest across one leg.

Quickly pulling this away as it starts to saw into his flesh (actor Gunnar Hansen performed this stunt himself, with a hidden metal plate beneath his pants), Leatherface limps upward. The semi having been abandoned, the driver having run away and vanished to be seen no more, Sally jumps into the bed of a pickup truck that does a U-Turn to come to her aid. Driving away, finally clinging desperately to the vehicle that has "saved" her, we realize that the nightmare she has just endured has destroyed her mind. Her ceaseless screams become peals of laughter, as her blood-streaked face ripples joyously into uncomprehending lunatic glee.

But this is not the final scene.

The final scene is a rage-filled, bizarre "dance" by Leatherface, flinging his chainsaw about wildly under the blazing, setting Texas sun. And then we suddenly stop.

Return of the Dead

So what does all of this mean? Clearly there is a subtext here, a submerged metaphorical meaning, wherein the fresh-faced future is lured, like a bevy of unsuspecting mice, into the hideous maw of a murderous trap. Devouring the future, the necro worshipers of the Texas Chainsaw "Death Family" have succumbed to the deterioration inherent in the social conditions that have seen their lineage decay, Lovecraft-like, from the staid, conservative and Victorian (albeit Texan) past, to something more akin to bestial, primitive blood sacrifice. It is as if the opening scenes of solar flares projected over the title sequence and credits hints at the dark, bloody practices of cannibalistic sun worship and human slaughter--but surely not. Is it that these natural cosmic forces have conspired to derange the senses of the hideous, bloodthirsty, anthropophagus clan? The hidden idea of submerged sin, of death being forestalled (Grandpa being an excellent example of this), of the past and the death-force being the cause of exaltation; the ghoulish sacrament of cannibalized flesh; the ritualized slaughter of humans taking the place of the butchering of livestock; this seems the allegorical meaning, even if unintentional. The family reaches back toward the grave, and even further, to an ancient observance that they truly can never comprehend.

And this is, perhaps, because being "put out of jobs" by the progress of industrialization, they have slipped from the perch of civilization; their incestuous, degraded line reverting to the primitive state lurking, always there, beneath the surface, like the degraded, cursed blood of the Usher's in Poe's Fall of the House of Usher.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was written and directed by Tobe Hooper, whose other most famous film, Poltergeist (1982), a supernatural horror blockbuster, featured the story of a new, modern home in the suburbs being built over a cemetary, to horrific results. In that film, the spirits of the dead, the transgressing against the past, is rewarded (or rather, punished) by the literal "bursting forth" of caskets and corpses hidden below the earth, those unquiet dead reeking vengeance on the modern world that has sought to subsume them below. They are the crepitating ghost of something bad, something incestuous and evil, something from the past that is coming calling; the dead rocked in their graves, cosmic and astrological forces driving their mendicants, thir worshipers to more vile, primitive and atavistic acts, in the orgiastic bloodletting that is The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

It is a ritualized human sacrifice, to propitiate the unquiet spirits of the ancestors, by a fallen line that has been betrayed by a world that has left them in the dust, to decay, and moved on without ever looking back.

The past devours--in this case literally--the present, the bodies of the young and beautiful; amidst a house of horror and decay and death. It is Grandpa being offered Sally's blood from her sliced finger, in a vampiric ritual that makes little sense in relation to anything else in the film--except as a metaphorical instance.

And that, a much as anything else, is at the great, dark heart of this seemingly deathless celluloid shocker.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) Trailer

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.