Skull Trophies | World War 2

World War 2 Horror Story

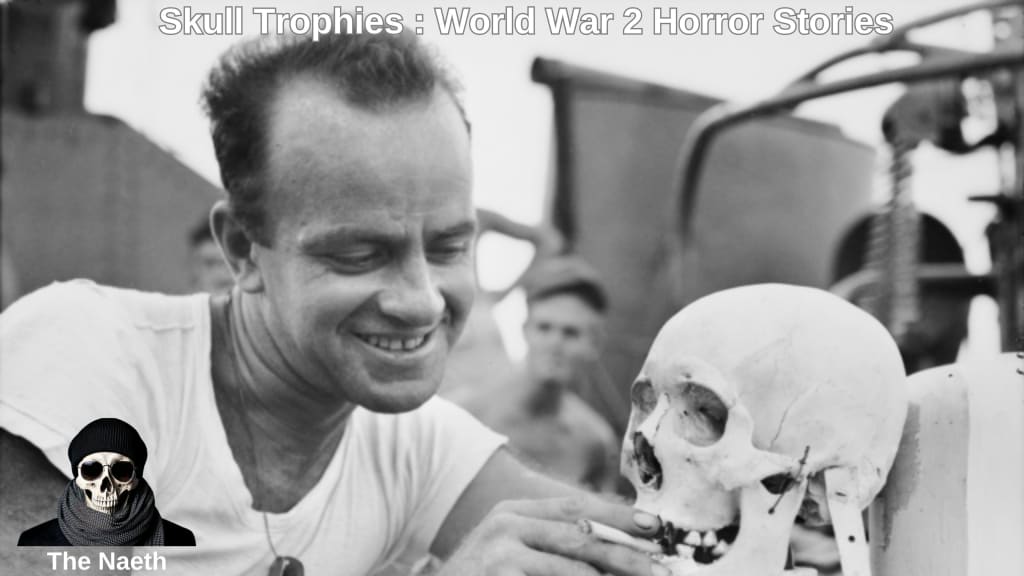

During World War II, members of the United States military who were stationed in the Pacific theater of operations mutilated Japanese service soldiers who were either dead or disabled (hors de combat). Body parts were taken from Japanese military men as "war souvenirs" and "war trophies" as part of the mutilation of Japanese service personnel. Teeth and skulls were the "trophies" that were taken the most often, while other parts of the body were also gathered.

There was such a broad prevalence of the habit known as "trophy-taking" that it was portrayed widely in publications such as magazines and newspapers. Representative Francis E. Walter of the United States of America is said to have presented Franklin D. Roosevelt with a letter opener fashioned of the arm of a Japanese soldier in the year 1944. Roosevelt subsequently issued an order for the letter opener to be returned and demanded that it be buried in the appropriate manner.

It was also extensively publicized to the Japanese public, where the Americans were represented as "deranged, primitive, racist, and inhuman." The Japanese people was particularly affected by the news. In addition to this, a prior photograph from Life magazine of a young lady holding a skull trophy was published in the Japanese media and portrayed as a symbol of American brutality, which resulted in widespread shock and indignation throughout the country.

This conduct was expressly condemned by the United States military, which gave supplementary guidelines as early as 1942, and it was formally outlawed by the United States military itself.

Despite this, the behavior was only occasionally prosecuted, and it persisted throughout the entire war in the Pacific theater. As a consequence, it led to the ongoing discovery of "trophy skulls" of Japanese combatants that were in the possession of the United States, as well as efforts by both the United States and Japan to repatriate the remains of Japanese soldiers who had been killed.

A number of first-hand testimonies, including those of American personnel, confirm to the fact that body parts were taken as "trophies" from the bodies of Imperial Japanese forces that were stationed in the Pacific Theater of Operations during World War II.

The phenomenon has been attributed by historians to a campaign of dehumanization of the Japanese in the media in the United States, to various racist tropes that are latent in American society, to the depravity of warfare under desperate circumstances, to the inhuman cruelty of the Imperial Japanese forces, to a desire for revenge, rage, outrage, or any combination of these factors.

There was such a common practice of taking so-called "trophies" that by September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet issued an order that said, "No part of the enemy's body may be used as a souvenir." He further stated that any American personnel who violated this policy would be subject to "stern disciplinary action."

Among the mementos, trophy skulls are the ones that have the greatest notoriety. Teeth, ears, and other such body parts were also stolen, and during certain instances, they were altered in some way, such as by having text written on them or by fashioning them into other artifacts or utility.

A image that was shot by Ralph Morse during the Guadalcanal battle had been published in Life magazine.

The photograph depicted a severed Japanese head that had been propped up by United States Marines underneath the gun turret of a Japanese tank that had been knocked out. Letters of criticism were received by Life from those who were "in disbelief that American soldiers were capable of such brutality toward the enemy." "War is unpleasant, cruel, and inhuman," the editors reacted to the editors' statement. Furthermore, it is more perilous to forget this than it is to be completely taken aback by reminders. However, the number of complaint letters received by the picture of the severed head was less than half of the number received by an image of a mistreated cat in the exact same issue. This suggests that the response from the United States was not considerable.

Years later, Morse said that when his battalion came across the tank with the head mounted on it, the sergeant cautioned his men not to approach it because it may have been put up by the Japanese in order to draw them in, and he worried that the Japanese could have a mortar tube that was focused in on it.

Morse mentioned that the sergeant's warning occurred after his unit came across the tank. The following is how Morse expressed his recollection of the event: "The sergeant tells everyone to stay away from there, and then he turns to me." What he says is, "You, go take your picture if you have to, and then get out of here as quickly as you can." After that, I went over, grabbed my photographs, and then rushed like a madman back to the location where the patrol had halted.

In the month of October 1943, the United States High Command voiced its concern on recent media stories that discussed the mutilation of the deceased by the United States. Some examples that were provided were one in which a soldier used Japanese teeth to make a string of beads, and another in which a soldier was shown with images demonstrating the stages involved in preparing a skull, which included boiling and scraping the skulls of Japanese people.

Winfield Townley Scott, an American poet, was working as a reporter in Rhode Island in 1944 when he saw a sailor displaying his skull trophy in the office of the newspaper. This resulted in the creation of the poem "The U.S. Sailor with the Japanese Skull," which detailed one process for the preparation of skulls for trophy-taking. According to this procedure, the head is skinned, then dragged in a net behind a ship in order to clean and polish it, and last, it is cleaned with caustic soda.

A number of cases of mutilations are mentioned in the notes that Charles Lindbergh documents in his journal. During the entry for the 14th of August, 1944, he makes a note of a conversation he had with a Marine officer who said that he had seen a large number of Japanese bodies that had either an ear or a nose severed.

The majority of the skulls, on the other hand, were not obtained from recently deceased Japanese individuals; rather, the majority of them were from corpses that had already undergone partial or complete decomposition and had been skeletonized.In addition, Lindbergh wrote in his notebook about his experiences when stationed at an aviation base in New Guinea. According to Lindbergh, the soldiers there executed the Japanese stragglers who were still alive "as a sort of hobby" and often used their leg bones to carve tools.

Comments (1)

Made me feel sick well written ♦️♦️♦️♦️