Ought to Have Remained Hidden: Psychoanalytic Theory in Us (2019)

Or: Out of the tunnels and onto the moebius strip.

WARNING: Spoilers for Us (2019) and Psycho (1960)

In 1816, German writer Ernst Hoffmann published the short story “Der Sandmann”. The story revolves around a man named Nathanael who still lives with his childhood fear of having his eyes stolen by the titular Sandman, and in adulthood, meets a man who bears an eerie resemblance to the Sandman, thus plunging him into mania. The story was later cited in Sigmund Freud's 1919 essay "The Uncanny". In this essay, Freud elaborates on the uncanny (unheimlich in his native German), or that which is strangely familiar, a concept previously developed by philosopher F.W.J Schelling and psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch. Freud states in the essay that "According to (Schelling), everything that is unheimlich that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has been brought to light." 144 years later, in 1960, Alfred Hitchcock released arguably his most iconic film, Psycho, which was dubbed "the first psychoanalytic thriller" by Serge Kaganski in his 1997 book Hitchcock.

In director Jordan Peele's 2019 film Us, Adelaide Wilson is haunted by a childhood memory of having encountered her own doppelganger, before she and her family (along with seemingly everyone in the continental United States) are terrorized and murdered by doppelgangers known as "The Tethered". The Tethered live in tunnels, survive on raw rabbit for sustenance, and are forced to mimic the actions of their above-ground counterparts, whether they want to or not. For instance, Adelaide's doppelganger, "Red", states that she was forced to enter a relationship with Abraham, the Tethered counterpart of Adelaide's husband Gabe, and that "it did not matter if she loved him." Anytime someone above ground undergoes any kind of surgery, the Tethered are forced to self-mutilate in order to mimic the surgery; Red states that because Adelaide underwent a c-section, she was forced to cut her son, Pluto, out of herself. In the end, the film reveals that Adelaide's encounter with her doppelganger went deeper than she let on. It was Adelaide herself who was the Tethered, and who trapped Red (the original above-ground Adelaide) in the tunnels before escaping and stealing her life.

The concept of the doppelganger, the uncanny double, is inherently Freudian in and of itself, but psychoanalytic theory is seldom if ever brought up in discussions relating to Us. This is likely due to the fact that the majority of the films symbolism is related to social inequality in the United States, and therefore analysis of the themes present in the film focus on that. But the psychoanalytic themes run deeper than the concept at the heart of the film's premise. Many of them mirror psychoanalytic symbolism found in the original psychoanalytic thriller, Psycho.

The New Psychoanalytic Horror

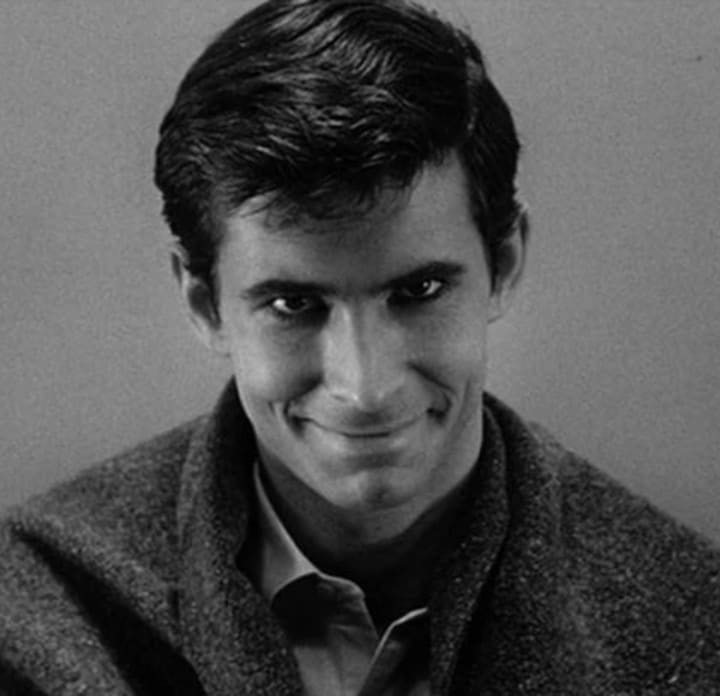

In the essay "In His Bold Gaze My Ruin Is Writ Large", Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek offers an interpretation of Alfred Hitchcok's 1960 film Psycho which posits that Norman Bates and Marion Crane are uncanny doubles of each other. Marion's story, Zizek says, is the world of contemporary American life, while Norman's world is its nocturnal reverse. Zizek states that their worlds are not separate, but in fact occupy two sides of a moebius strip, and that by progressing far enough on one side, one will suddenly find themselves on the other. This transition takes place, Zizek argues, as Marion drives from the used car dealership to the Bates Motel, and this is elaborated on by Margarita G. of plainflavouredenglish and the YouTube channel Is This Just Fantasy?. In her essay "Psycho's Moebius Strip (Or: How Marion got her uncanny lunch and ate it, too), Margarita argues that the turning point, the moment where the film takes us from the daylight of 1960s American life to its noir-ish mirror image "it is not the infamous shower scene, but occurs earlier on in the film, during Marion's drive to the Bates Motel." Marion stares ahead onto the road, imagining the voices of her employer and coworkers realizing that she has absconded with 40,000$ in cash. Cuts are frequent, the sky darker with each one, as Marion loses track of time, before looking into the camera, and offering an unnerving smile that foreshadows Norman's iconic grin at the end of the film. This is the moment Marion crosses the moebius strip, and enters Norman's reality, the subjective reality.

Like Psycho, Us can be understood as a film that takes place on a moebius strip, each side representing a different reality. On one side is middle-class American family life, and on the other is the world of the Tethered, its nightmarish flip side. Also like Psycho, Us moves us from the former to the latter, from objective reality to its subjective, insane counterpart, relatively early in the film. Earlier than may initially be believed, anyway. It is not when Adelaide ventures into the tunnels to save her son, nor is it Red and her brood first arrive on the Wilson's vacation property. Even prior to that, Adelaide expresses a sentiment of lingering unease and discomfort. She notices a series of strange coincidences, and tells Gabe "I don't feel like myself." This is not only foreshadowing for the twist ending of the film (in a way, she actually isn't herself), but it points to the fact that though she appears to be inhabiting the daylight side of the moebius strip, she's already on the other side. The moment of "rupture", as Margarita calls it, comes within the first twenty minutes of the film. Adelaide, as a child, wanders away from her parents at night on the Santa Cruz boardwalk. She ventures down to the beach, and, as the sky opens and it begins to pour, she slips into a hall of mirrors. Naturally, Adelaide's pathway becomes unclear, as the mirrors morph the room. A narrator (voiced by Peele himself) tells her "find yourself." After being frightened by an owl, and growing more unsure of herself by the second, the younger Adelaide backs into her doppelganger for the first time. She turns, meeting her own eyes, and her expression is one of terror. Though the scene cuts away before we're shown the ensuing altercation, we can be sure that Adelaide has been permanently altered by this confrontation. This marks the crossing from one side of reality to the other, the moment that the film crosses to the uncanny side of the moebius strip, into subjective reality.

This moment in Us also mirrors another shift that occurs in Psycho, albeit later. In this moment, when the doppelganger turns around and offers Adelaide that frightening grin, the focus of the narrative changes from Adelaide herself, to the doppelganger. Rather, the doppelganger, the "Tethered" version of Adelaide, forcibly removes the original Adelaide from the position of "protagonist", by violently attacking her and trapping her in the tunnels beneath. The original Adelaide is forced to re-assert her position in the narrative as Red, maniacal leader of the Tethered uprising, the primary antagonist. Similarly, in Psycho, 3/4ths of the way through the film, Norman (disguised as mother) usurps Marion's position as the focus of the narrative in an even more violent fashion. Marion, like Red, is banished from the light, though re emerges later as her car is pulled from the swamp on the Bates property.

There are clues sprinkled throughout the film that Adelaide is different from other people. These clues seem innocuous at first, she snaps out of rhythm with Luniz's "I Got 5 On It", a hip-hop classic whose haunting melody provides the bones for the film's score. While the rest of her family eats fast food, she eats a relatively insubstantial lunch consisting solely of strawberries. On the beach, she tells family friend Kitty Tyler "I have a hard time just... talking". But as the narrative progresses, and the Tethered wreak their biblical vengeance, Adelaide reveals herself to be decidedly uncanny; most notably, while killing the Tethered. Both after killing the double of one of the Tyler children, and ultimately defeating Red, Adelaide grunts, clicks her teeth, making noises similar to the ones we hear the Tethered make.

Conversely, Red is the most heimlich of the Tethered, most notably in her capacity to speak English, which no other Tethered are able to do. Of course, the reason why Red can speak English, and why Adelaide snaps out of rhythm is revealed in the final minutes of the film. Adelaide is Norman disguised as Marion, whereas Red is Marion being mistaken for Norman. Not only are they uncanny doubles of each other, but each is occupying the others side of the moebius strip.

The Three Levels of Santa Cruz

In "The Pervert's Guide to Cinema", Zizek makes a comparison between the three levels of the Bates house and Freud's three levels of awareness. The three levels of awareness, as anyone who's taken any psychology courses knows, refers to the conscious, unconscious, and preconscious, identified with the id, ego, and superego respectively. The main floor of the house represents ego, or the conscious. The ego, according to Freud, is the level which organizes conscious thought. The top floor represent superego. The superego is more concerned with morals and ethics, learned from figures of authority, like our parents. For example, "Mother" berates Norman for his attraction to Marion. The cellar, where Lila Crane discovers the corpse of Norman's mother at the climax of the film, represents the id. The id is the most basic level of the human personality, the "reservoir of illicit drives" in Zizeks words. As Daniel Brennan points out in his paper "The Lady In The Van and the challenge of Psycho", the id "constantly communicates its need for pleasure." The id knows no morality, only the basic carnal drive for pleasure and survival. Like the Bates cellar, it is devoid of human furnishings beyond the most basic level, and it is where Norman banishes the evidence of his heinous crime, matricide. It is kept out of his conscious mind, and away from the authoritarian gaze of his "mother" personality.

Us takes place primarily in three locations, which themselves can be understood as representations of Freuds three levels of personality. Though they are not literally one on top of the other like the levels of the Bates house, what they each represent symbolically mirrors that.

The beach house where the Wilson family stay for their vacation is symbolic of the Superego. It is here where the gaze of authority is felt, where morals and ethics are enforced, specifically by maternal authority. It is Adelaide who tells Jason to eat his lunch after they arrive, who (sympathetically) chastises him for playing in the closet that cannot be opened from the inside, and who tells Zora to turn off her phone at bedtime. This trend of maternal authority reigning supreme in the beach house continues when the Tethered arrive. As soon as the "boogieman's family", as Jason puts it, enters the house, Red is in charge. She sits, as if occupying a throne, telling the Wilsons the story of the girl and her shadow, before dolling out orders to the Wilsons as well as her own family. This sequence calls to mind another scene in Psycho. After Marion arrives at the Bates motel, Norman initially invites her for dinner in the house. However, Marion overhears "Mother" forbidding Norman from bringing Marion into the home, subjecting him to a tirade of abuse. Both Red and the "Mother" personality set out the rules of conduct in their homes, and both subject those under their control to terrifying diatribes. Zizek contends that the commands of the superego metaphor in Psycho are unethical. The same can be said of Red's commands in the beach house, though they may be in some way morally justified in her mind, the actions she and her people take to right the perceived wrongs are unethical. To quote Zizek directly, "There is always some aspect of an obscene madman in the agency of the superego". As is the function of the superego, in the beach house, morality is enforced through parental (maternal) authority.

The middle of Freud's tripartite personality is the ego, which is represented by the Santa Cruz boardwalk in Us. Just as the ego is the intermediary between the desires of the id and the morals of the superego, the boardwalk serves as the bridge between the world of the Tethered and those above ground. The ego, as Freud proposed it, seeks pleasure, yet is still ruled by reason. The Santa Cruz boardwalk is a tourist destination, somewhere people go to experience pleasure. Yet, as it is above ground, it is still governed by the morality established in the superego, in the beach house. Adelaide sets out expectations for her family's conduct on the boardwalk ("we leave before dark"), which is informed by trauma she encountered as a child. In Psycho, Norman is berated from the superego level of his home for not meeting the ideal his ego has created, while still being subjected to the whims of his id (Brennan). According to Id, Ego, and Superego from the website Simply Psychology, though the ego is often charged with regulating the id, it sometimes proves to be weaker. In Us, the boardwalk fails to contain the Tethered uprising, despite this being the apparent purpose of the hall of mirrors. Just like the main floor of the Bates house, the Santa Cruz boardwalk exists under the authority of the superego while trying (and failing) to contain the carnal aggression of the id.

Lastly, the tunnels which house the doppelgangers is symbolic of the id. The id is the most primal level of the human personality, driven by basic carnal desires, and remains unchanged by experience. It is unconscious, and unaffected by the outer world. In Us, Red asks Adelaide "How it must have been, to grow up with the sun?" Those in the tunnels, though they mimic the actions of those above, are completely detached from the above world, until they force their way up. Furnishing wise, the tunnels are sparse, emphasizing both the metaphor of poverty in the film's social themes, and the idea of the id as primitive; it is devoid of the embellishments that come from experience. This is also true of the Bates fruit cellar. Both spaces are untouched by natural light, not built for comfort, with concrete walls and imposing, sinister artificial light. As Red described when she is first introduced, the tunnels are without any of the comforts of the world above, yet the Tethered still hunger, and still reproduce (in tandem with their surface-dwelling counterparts). The basic desires for survival and pleasure are present in the tunnels, but these are fulfilled in incredibly carnal and chaotic fashions. The world of the Tethered, the id, is ruled by chaos.

The Itsy Bitsy Spider

In "Psycho's Moebius Strip", Margarita explores how Marion's fantasy of domestic respectability is fulfilled in a twisted way by her experience at the Bates Motel. And just as Norman, as Marion's uncanny double, consumed and then replaced her, the narrative reaches back around. The film returns the viewer to subjective reality, to the original side of the moebius strip. Marion emerges in the trunk of her car, pulled from the swamp, Norman is consumed by his mother persona, "like Marion, a neurotic woman concealing a crime". Us ends in a similar way, bringing the events full circle, and leaving the viewer wondering which side of the strip is which.

In the tunnels, Adelaide impales Red with the fire poker she has been armed with for the majority of the film. Red, choking on her own blood, whistles "the itsy bitsy spider", before Adelaide snaps her neck, bringing the violence to an end. Adelaide was shown whistling the same melody in the hall of mirrors as a child. Adelaide then finally tracks down her son, who Red had taken in a moment of confusion, but Jason seems to know things still aren't normal. Finally, as the family drive away from Santa Cruz, the audience learns the truth. Adelaide's flashback reveals that she was the Tethered one, and trapped Red in the tunnels as a child. Like Marion Crane, Adelaide had spent the majority of the film trying to conceal a crime. Her neurosis concerning the boardwalk revealed to be guilt. Though Red is no longer alive (also like Marion), she re-emerges as the protagonist, not as an aggressor but as the victim of two terrible crimes. Adelaide turns to Jason, and as she realizes what he knows, smiles. She is once again the Norman of the story, who has committed and is successfully concealing horrible secrets. The film has returned to subjective reality through this revelation. As Margarita wrote, "the uncanny night ends", and the Wilsons drive away into the light, but the shadows of the uncanny will never fully dissipate.

About the Creator

jenny

all hail the universal friend

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.