There's something of a stigma that comes with PG-13 movies, and rightfully so. It's an extremely fruitful audience–attracting teenagers not yet seventeen, the heart of profit. PG-13 horror is practically a riskless market, and thus, houses some of the most passionless, terrible, cash-grab films of their respective years. And it works.Truth or Dare, a movie with a 15% on Rotten Tomatoes and an even more dismal average audience reaction, grossed almost a hundred million dollars worldwide. A hundred million. Ouija, sporting an even lower 6% on RT, made over a hundred million. You'll find similar examples littered through the past decade: Slender Man, Wish Upon (what is it with Joey King and these movies?), The Lazarus Effect—it happens incessantly. As much as I want to fault these filmmakers for their unending heartless production, I understand where they're coming from. It's a profitable market.

But there are some amazing PG-13 horror movies, too. The Sixth Sense. Insidious. The Ring. So how are you meant to tell the difference?

I don't know if this is just me or not, but I feel like bad movies give off a certain vibe. A technical manufactured-ness. I'm sure you knew as soon as you saw the poster that Truth or Dare and Slender Man weren't going to be good. Initially, I thought I knew that Escape Room, Columbia's first film of the new year, was going to be terrible. It hit every single marker of a bad movie—it had a gimmick, a vast and therefore massively relatable cast of characters, shallowness, an element of current culture, and probably a dozen more. It almost felt intentional.

I was expecting a terrible movie, so of course, I bought tickets opening day.

Escape Room might have one of the worst opening scenes of all time. The movie opens with Logan Miller's character, Ben, falling through the ceiling of an ornate room. He stands up instantly and starts speaking his thoughts aloud, like a children's character on a cartoon would do when trying to solve a puzzle. It felt extremely juvenile, almost like a judgment of the audience. It assumed viewers to be incapable of assumption or context clues, instead of laying everything out in pointless dialogue, dialogue that made little in-universe sense and was undeniably only there to explain the situation to the viewer. I elbowed the boy I went with and said, two minutes in, "I told you it would suck."

Although the first scene by far is the worst, the entire exposition is comparatively bad. It's formulaic. It runs through a "slice of life" for three of the six main players, Taylor Russell's character Zoey first to be introduced and thus set to be the main. It's poorly done, generally. It's devoid of art, of style, of anything. Imagine a textbook as a movie.

It's a bad start, and it stays bad until the game starts.

I remember being pleasantly surprised at this point. I've never been good at guessing movie twists, but the room you're meant to believe is the waiting room actually turns out to be the first room of the game. It was a clever start to something that would go on to be creative in the way Cube is creative—not as well, but, definitely something.

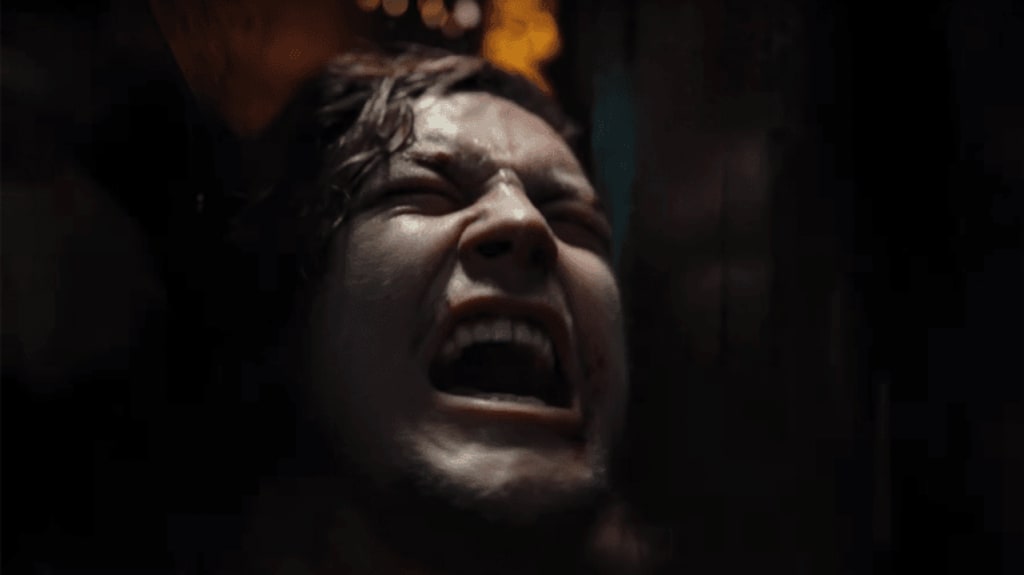

It gets dark quickly. It is revealed that a badly scarred Amanda (played by Deborah Ann Woll) has gone through fire-related trauma, first subtly and then all too obviously when the room becomes a giant oven. Yeah, giant oven. Still sounds juvenile, but it's executed better than it sounds. In particular, the characters discover an attendant they believed they were speaking with turns out to be a mannequin–and shots of the smiling, plastic woman melting are interspersed as time goes on. It's a little detail that goes a long way.

The movie reminded me of Saw in its execution of creativeness. It's that same breed of disturbed, executable versatility that is just so freaking entertaining, regardless of a film's actual goodness. But I guess it depends on the individual's idea of what a film should be.

Anyway, the movie continued to be clever (clever, not smart. This is not a smart movie). It connected the characters to their environment well, it created authentic relationships, and it had a subtlety that was, at certain points, close to flawless.

My point is, the movie had clear ups and downs. It had good action scenes, good pacing, and decent staging. But for every compliment, there's a flaw–from an over-suspension of disbelief to Taylor Russell's mediocre at best performance. An average film, it would seem.

But it isn't average, it isn't mediocre, for one reason alone: audience expectation.

I expected it to be a 3/10, so when it turned out to be a 6/10, it essentially exceeded my initial perception by twofold. That's never a bad thing for a movie to do.

This technique is manipulative, risky, dishonest, and not the way film should be handled. It's against the art of it all. I can see that, anyone can see that. But it works. It works well, and it's hard for me to fault any director for that.

Escape Room is not artful, it's by no means a good movie, but it gets away with not being one. I feel the need to talk about it because of how pleasantly surprised I was, and this type of movie is pretty much the only kind that could pull off this expectation tactic. Normally, when a movie looks bad, people don't buy tickets. It makes sense. But bad horror is so fun. Ask anyone who went to see The Bye-Bye Man (myself included)–I can guarantee not one person went into that thinking it was going to be any good. So it's real easy to get people to come, which in of itself is half the battle–but making it not suck when you could get away with it? That's clever enough to trick people into thinking you can actually make a movie.

Look low and aim high, I suppose. Cheers to this ridiculous movie.

About the Creator

hannah brostrom

movies!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.