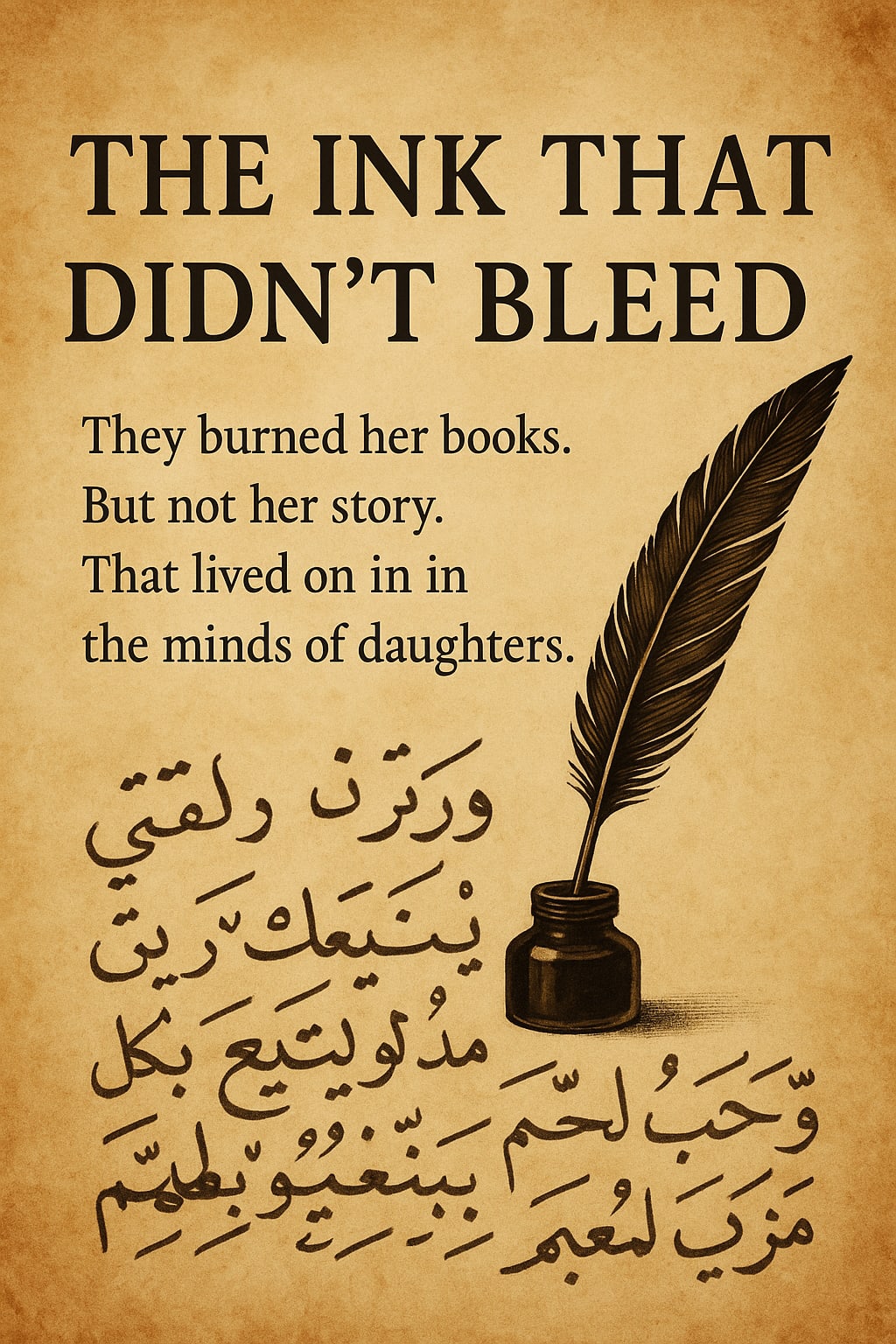

The Ink That Didn’t Bleed

They burned her books. But not her story. That lived on in the minds of daughters

In 1637, a woman named Safiya al-Basri disappeared from every official record in the Ottoman Empire.

Her crime wasn’t theft.

It wasn’t treason.

It was something far more dangerous.

She taught women how to read.

---

Safiya lived in the back alleys of Aleppo, behind a tailor’s shop that smelled of rose oil and burning coal. She had once been the wife of a court scribe, a man who died suddenly—poisoned, some whispered—after accusing a governor of corruption in a public letter.

After his death, Safiya never remarried. She turned their home into a quiet school.

She taught in secret.

Taught under candlelight.

Taught girls with calloused hands and eyes full of questions.

She wrote lesson scrolls by hand. Not just in Arabic, but also in Persian and Greek. She believed women needed more than religion. She believed they needed history, medicine, poetry—power.

---

They came for her one spring night.

Men with polished boots and names no one dared to repeat. They found the hidden scrolls, the scratched wooden slates, the ink-stained hands of her youngest student—a baker’s daughter named Yara.

They burned it all.

The scrolls.

The walls.

The smell of ash and paper lingered for weeks.

And Safiya?

She was never seen again.

---

Her name was removed from tax records.

Her husband’s death was reclassified as “natural.”

Her home was leveled and replaced with a guard station.

To history, she had never existed.

---

But history forgets one thing:

Mothers whisper.

Daughters remember.

Ink burns, but memory resists.

---

Yara, now seventeen, carried Safiya’s teachings in her spine.

She copied every poem she could recall from memory, using crushed berries and cloth scraps.

She taught her younger cousins how to sign their names, even if only in sand.

She married a stonecutter. Had five children. Two of them girls.

Each one taught the next.

---

By 1721, a group of women began passing hand-stitched books between the dye markets and the olive groves. They called them Black Petals—small, dark-bound books that looked like recipe journals, but held verses by Rumi, diagrams of healing herbs, and questions like:

No one knew where the first of these books came from.

But one bore the initials “S.A.B.” on the back page, almost too faded to see.

And a line, carefully written in the margin:

Centuries passed.

Borders changed.

Names of emperors faded from stone.

But the name Safiya al-Basri survived in whisper.

She became myth.

A warning.

A symbol.

Mothers told their daughters to be careful—but also to be clever.

To learn, but in secret.

To write, but in codes.

To carry ink like it was sacred.

---

In 1910, an Armenian librarian in Beirut found a half-burned scroll inside the walls of a collapsing house.

It had no date. No clear author.

But the calligraphy was unmistakably elegant.

On the back, in Ottoman Turkish:

The librarian published excerpts in a journal under the title “Letters from the Smoke.”

Scholars debated its origin.

Some dismissed it as literary fiction.

Others saw it as the missing voice of a century that had too few women’s names.

But among Arab feminists, one name quietly resurfaced:

Safiya al-Basri.

---

She never had a monument.

No statue.

No portrait.

But in 2021, a group of schoolgirls in Aleppo painted her name in violet across a crumbling wall, beside a drawing of an open book.

The paint was removed by morning.

But someone photographed it.

It was shared online under the hashtag

The post went viral.

Not because it was flashy.

Not because it had music.

But because people recognized her.

Not her face. Not her voice.

But her fire.

The same fire that lives in women who teach quietly, who smuggle books in lunchboxes, who write poems in exile, who whisper answers behind closed doors.

The same fire that never learned to obey.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.