The Hearth of Habiganj

A Medieval Bengali Village Story

A Medieval Bengali Village Story

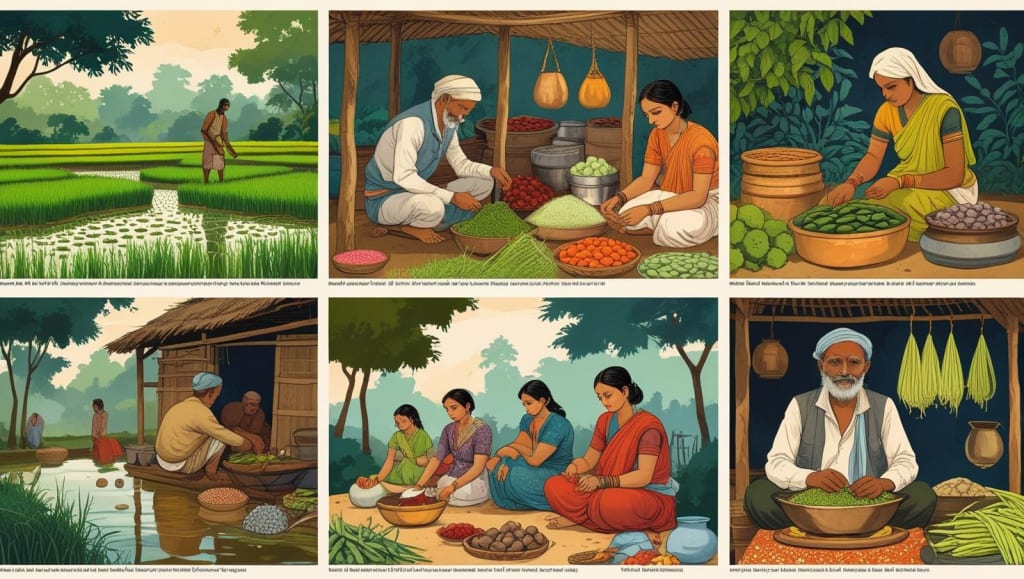

In the heart of medieval Bengal, where the Meghna River curved like a silver thread through endless green, lay the village of Habiganj. It wasn’t a place of kings or conquests, but of muddy paths, straw roofs, and lives woven into the seasons’ rhythm. I’m Shyamal, a potter’s son, and this is my tale of a year in our village—our food, our struggles, our small joys. It’s no epic, but it’s ours, told as if we’re sitting by the fire, passing a clay plate of rice and stories.

Spring: The Season of Sowing

Spring arrived with a warm breeze, waking the fields. My father, Baba, shaped pots by the riverbank, his hands slick with clay, while Ma tended our small rice paddy. Food was simple but deliberate. Breakfast was bhaat—rice boiled soft in an earthen pot, paired with shak we foraged from the forest’s edge. The greens—bitter kalmi or tender water spinach—were free for those who knew where to look. My sister, Lila, and I would wander before dawn, baskets swinging, hunting for kathal seeds or wild amra fruit. The forest was generous but tricky; one wrong root could sicken you. Ma taught us the old ways—her mother’s knowledge of which leaves soothed and which poisoned.

We didn’t hunt much. Deer or boar were for the zamindar’s men, who rode through with bows and loud voices. Instead, we trapped small fish in woven nets or bartered with fishermen for ilish or rui. A good catch meant a feast: fish curry with green chilies, the scent rising from Ma’s clay oven. But most days, it was rice and dal—lentils simmered with a pinch of turmeric if we had it. Spices were rare; only the headman’s family could afford cumin or coriander from the distant market in Sylhet.

Preserving food was a village art. After a good harvest, we’d dry fish in the sun, stringing them like garlands to hang under the eaves. Rice was pounded into chira—flattened flakes that lasted months. Lila and I helped Ma bury yams in cool earth to keep them through the heat. Barter was our currency. Baba traded pots for a neighbor’s extra rice or a basket of kochur loti. Once, he swapped a wide-mouthed matka for a goat kid, which we named Kalo and raised for milk. Every bite tied us to the land and each other.

Summer: The Heat and the River

Summer scorched Habiganj. The river shrank, and the paddies cracked under the sun. Food grew scarce, and we leaned on what we’d stored. Breakfast might be chira soaked in water, mixed with a few jujube fruits Lila found. Foraging became a hunt. We’d trek deeper into the forest, dodging snakes, to dig for wild tubers or pluck thankuni leaves for a bitter salad. The women led these trips, their chatter filling the air as they shared stories of spirits in the banyan trees or the time a tiger stole a cow.

Midday meals were light—a handful of rice with a thin dal or a shak bhaji of whatever greens we had. Fish were harder to come by; the river’s low waters made netting tricky. Sometimes, a neighbor would share a chingri prawn curry, and we’d sit in their courtyard, eating from banana leaves, the spice stinging our tongues. We repaid them with Baba’s pots or Ma’s woven mats. In summer, the village was a web of give-and-take; no one survived alone.

Evenings brought relief. We’d gather under the stars, cooking over a shared fire. Ma might fry kumro flowers in a batter of rice flour, crisp and golden. If Kalo gave enough milk, we’d boil it with rice for kheer, a rare treat. The elders told stories—tales of forgotten kings or the river’s moods. I remember one night, old Dadi Rupa spoke of a famine long ago, when the village ate only boiled roots for weeks. Her voice was low, but it held us all, reminding us how fragile our plenty was.

Monsoon: The Flood’s Bounty and Burden

The rains came, and Habiganj transformed. The river swelled, flooding fields but bringing fish—koi, magur, even slippery eels. We’d wade in, laughing, to set traps or cast nets. A good catch meant a feast: fish stewed with green mango, sour and rich, shared among neighbors. But the rains could betray us. One year, the river breached its banks, drowning our paddy. We salvaged what we could, eating half-rotted yams and chira softened in rainwater.

Foraging stopped; the forest paths were mud. Instead, we gathered keshur—water chestnuts—floating in the flooded fields. Ma would boil them, their nutty sweetness a small comfort. Rice was rationed, mixed with wild greens to stretch it. Dal became a luxury, replaced by watery soups of kolmi shak. We preserved what we could, drying fish or pickling mangoes when the trees were heavy. Baba’s pots were in demand—big ones for storing grain, small ones for pickling. He worked late, the wheel spinning under a thatched shed, while Lila and I carried clay from the riverbank.

Evenings were loud with rain and stories. We’d crowd into the headman’s hut, the only one with a raised floor, and share a pot of rice and fish curry. The children listened wide-eyed as the men spoke of battles far away or the goddess who guarded the river. Food bound us—every shared meal a promise to face the next storm together.

Winter: The Harvest’s Hope

Winter was kind. The fields dried, and the rice grew tall. We harvested together, singing as we cut the stalks. The first meal after the harvest was a celebration: rice piled high, dal thick with ghee bartered from a trader, and fish curry with fresh coriander from Ma’s garden. We ate on the ground, legs crossed, the air sharp with winter’s chill.

Foraging eased; the forest offered mushrooms and ber fruits. Lila and I competed to find the ripest ones, our fingers stained red. We still bartered—pots for vegetables, rice for milk. Once, a traveling merchant brought salt, and we traded two of Baba’s finest pots for a handful. Ma sprinkled it into a shak bhaji, and we savored every bite.

Winter evenings were for feasting. The village gathered for poush parbon, a harvest festival. We cooked pithe—rice cakes stuffed with coconut or jaggery—over open fires. The women sang, their voices rising above the crackling flames. Baba told me of his father, who’d seen a Mughal soldier once, his sword gleaming like the river. These stories, like our food, were plain but vital, rooting us to Habiganj.

The Cycle of Survival

Life in Habiganj wasn’t easy. Hunger was a shadow, always near. We ate what the land gave—rice, greens, fish, roots—and stretched it with care. Foraging was our skill, barter our wealth, preservation our shield. Every meal was a victory, every shared plate a bond. The forest, the river, the fields—they weren’t just places but partners, giving and taking in turn.

I remember one night, after a long day of pot-making, Baba looked at me and said, “Shyamal, the earth feeds us, but we feed each other.” That was Habiganj’s truth. Our food wasn’t rich, but it was honest. Our stories weren’t grand, but they were ours. And as I tell this by the fire, the clay plate warm in my hands, I hope you feel it too—the heartbeat of a village, simple and alive.

About the Creator

Shohel Rana

As a professional article writer for Vocal Media, I craft engaging, high-quality content tailored to diverse audiences. My expertise ensures well-researched, compelling articles that inform, inspire, and captivate readers effectively.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.