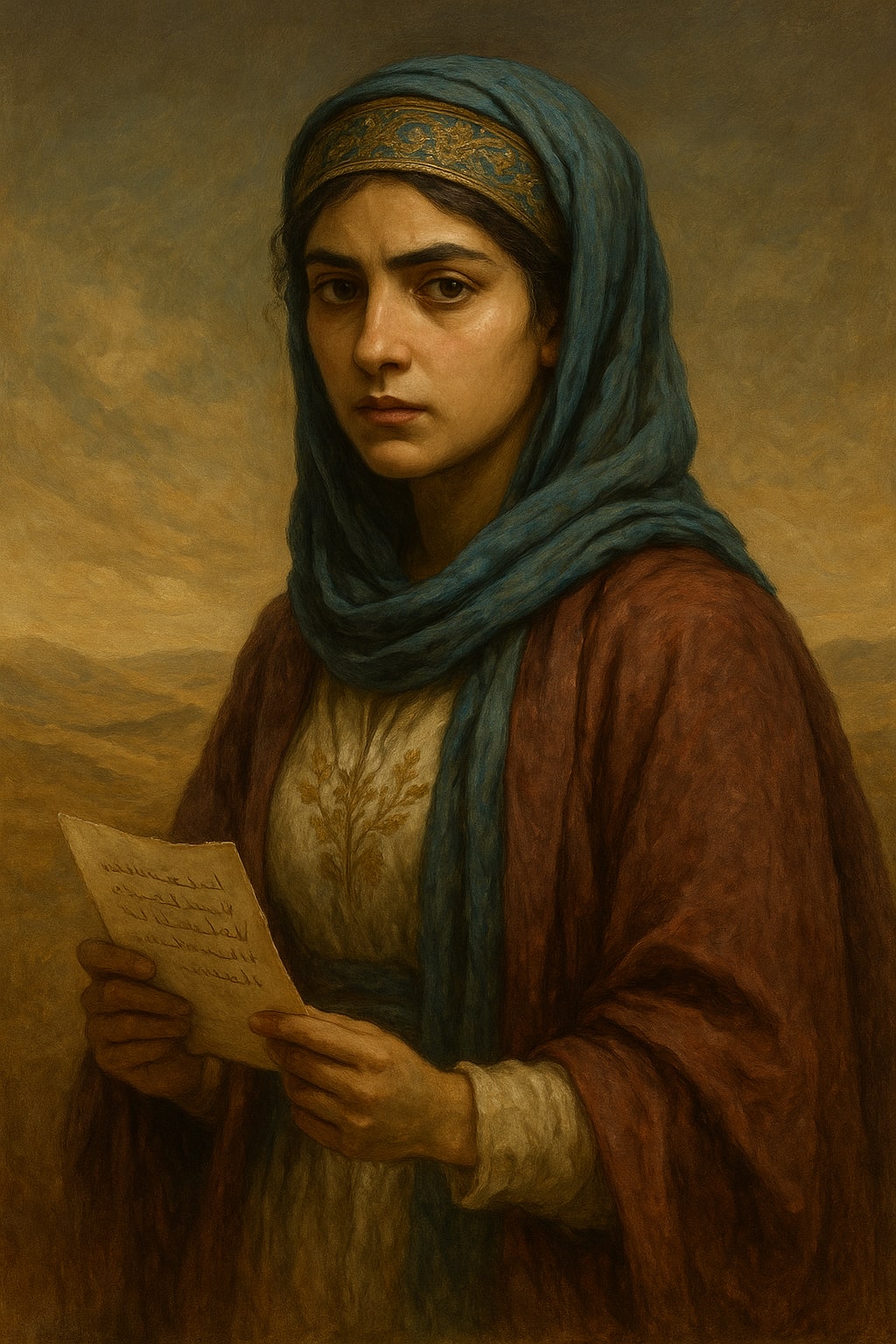

The Forgotten Flame: The Life and Legacy of Soraya al-Din

History

In the dusty archives of Cairo’s old libraries, tucked behind shelves of colonial records and royal decrees, lies a weathered leather-bound journal dated 1873. Inside, penned in both Arabic and French, is the testimony of a woman named Soraya al-Din—once a revolutionary, a poet, and a feminist before her time. Her name does not appear in most history books, though her impact shimmered briefly through Egypt’s early feminist movement before vanishing into silence.

Soraya was born in Alexandria in 1849 to a family of merchants who traded spices and books between Egypt and southern France. Unlike many girls of her time, she was educated at home by a French tutor who taught her to read Voltaire and Rousseau. But it wasn’t French philosophy that stirred her heart—it was her grandmother’s stories, told at night in whispered Arabic, about ancient Egyptian queens and warrior women erased by time.

By 17, Soraya had written her first collection of poems titled Voices Beneath the Nile, a passionate plea for women’s freedom in a society that bound them in both fabric and silence. Her writing was fierce, elegant, and filled with metaphor: women as the desert winds, men as the walls of ancient tombs trying to contain them. The collection was published in secret through a small French press, and within months, it was banned in Cairo.

Rather than silencing her, the ban emboldened her. Soraya began organizing quiet gatherings in her family’s courtyard—what she called Circles of Fire—where women shared stories, read poetry, and studied law, history, and the Qur'an not through the lens of male interpretation, but through the spirit of self-liberation. These gatherings soon grew too bold for the authorities. By the time Soraya turned 24, she was under constant surveillance.

Her political activism deepened when she met Jamila al-Hakim, a seamstress-turned-unionist from Cairo’s textile district. Together, they drafted The Petition of Daughters, demanding legal rights to education, divorce, and property—ideas deemed treacherous even by many progressive men of the era. They gathered over 600 signatures from women across Egypt and submitted it to the Khedive. The petition was never acknowledged, but the two women were.

In 1876, Soraya and Jamila were arrested under charges of inciting rebellion. Jamila was sentenced to forced labor in a textile mill. Soraya—due to her family’s wealth—was offered a deal: public renunciation in exchange for freedom. She refused. Instead, she was confined in a convent-turned-prison for “women of scandal.” There, she continued to write, hiding poems inside the seams of her robes, and smuggling them out through sympathetic nuns.

She disappeared from public record in 1881. Some say she died of illness, others whisper of an escape to Marseille, where she lived under a false name. Her journal—the one in Cairo’s library—was discovered in 1927 by a French-Egyptian historian, Amal Darwish, who tried to publish its contents. But publishers told her the story was “too obscure” and lacked “verifiable impact.”

Decades later, Soraya’s legacy lives only in fragments. A single stanza of her poetry survived in a 1930 anthology. One of her Circles of Fire notebooks was rediscovered in 2004 during renovations of a home in Alexandria. And yet, ask a history student today about early Egyptian feminists, and you’ll hear names like Huda Sha'arawi or Doria Shafik—powerful women, certainly, but ones who followed long after Soraya’s spark was first struck.

Why was she forgotten?

Perhaps because she didn’t write in institutions, or marry men of influence. Because her resistance was poetic rather than political. Because her voice was too early, too loud, and too feminine. Because history, for centuries, has had no patience for women who chose both rebellion and grace.

But that changes now.

By telling Soraya’s story, we write the page they never wanted us to read. And in doing so, we return her voice to the wind.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.