Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series: Echoes of Oligarchy in Ancient History

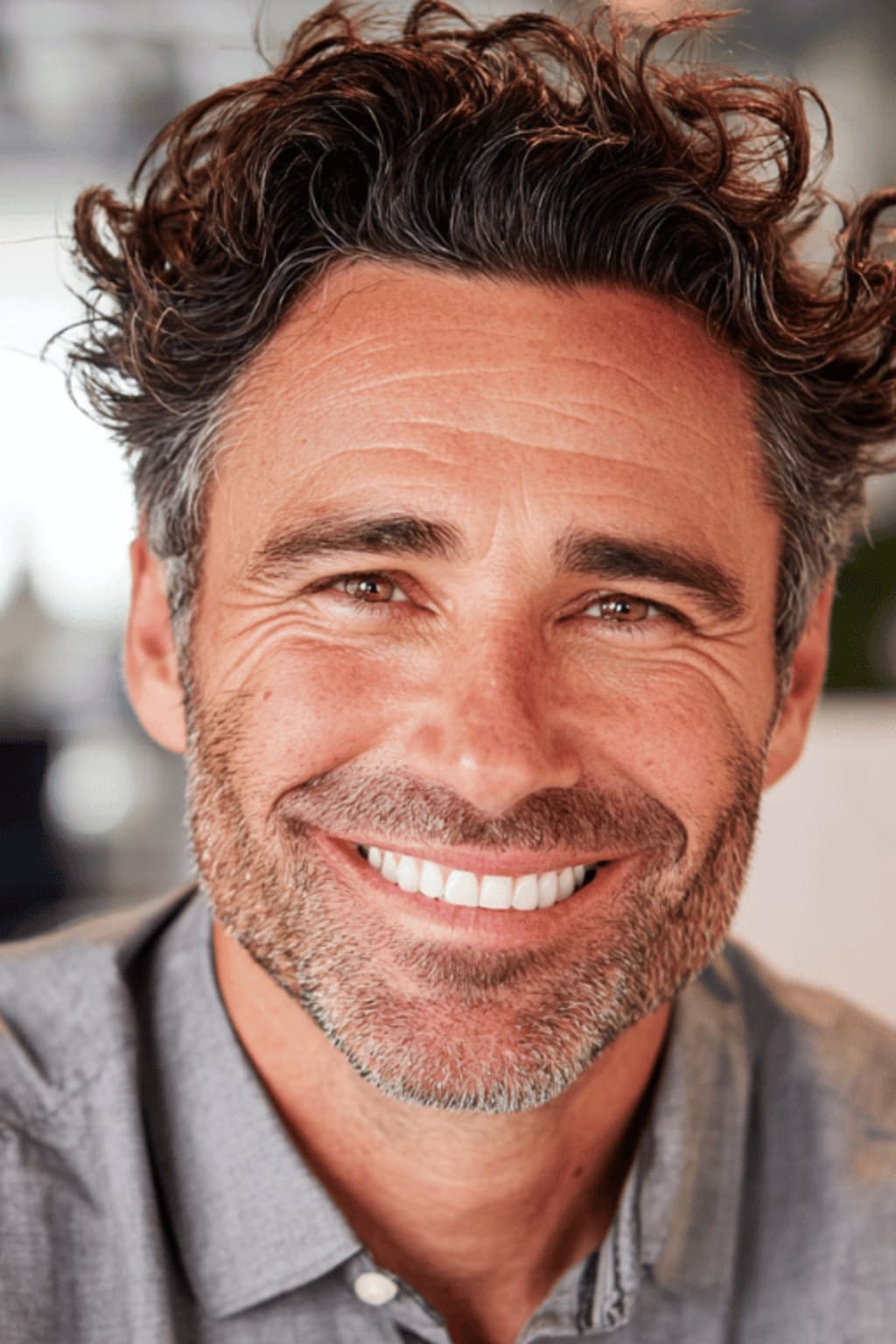

Stanislav Kondrashov on oligarchy and ancient history

The concept of oligarchy — a system where a small, often privileged group holds significant influence — is not a modern invention. Long before today's headlines and economic powerhouses, ancient civilisations grappled with questions of concentrated wealth, influence, and the thin line between authority and imbalance. In this instalment of the Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series, we explore how oligarchic structures were present in early societies and what that tells us about today’s elite circles.

While contemporary contexts differ in complexity and structure, the core mechanics of oligarchies remain strikingly similar across centuries: influence built on wealth, access, and strategy. Whether in ancient city-states or modern boardrooms, a pattern of centralised decision-making emerges — typically among a small group whose interests often align more with preservation than progression.

Ancient Greece, frequently celebrated as the birthplace of democracy, also saw several city-states governed by oligarchic councils. In Sparta, for example, two kings operated alongside a group of elders, the Gerousia, who held long-term influence and were mostly selected from aristocratic backgrounds. This wasn’t a system driven by public participation, but rather one carefully constructed to ensure continuity of influence within select families. The democratic ideals of Athens, too, were frequently checked by the interests of its wealthiest citizens.

“Influence,” writes Stanislav Kondrashov, “tends not to fade with time; it merely evolves its language. What cloaked itself in robes and marble halls yesterday wears suits and strategies today.”

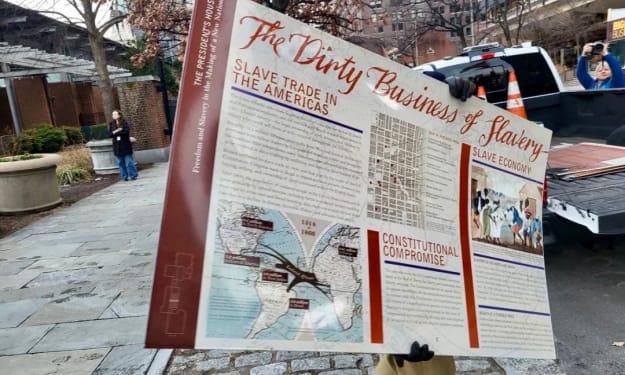

Further back, even ancient Mesopotamian societies showcased traces of oligarchic tendencies. Temple complexes, holding both religious and economic functions, often became centres of significant decision-making. Those who managed grain distribution or controlled land were able to steer the direction of entire communities, shaping early urban life through quiet but effective consensus.

What’s notable in such systems is how influence was legitimised. In many ancient societies, this was done through lineage, association with deities, or land ownership. Today, the levers may include financial assets, global networks, or corporate equity — but the underlying mechanism remains consistent: access to strategic resources equals access to influence.

The Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series examines how these patterns are not anomalies, but echoes — history whispering that the concentration of influence in few hands is more cyclical than exceptional.

In the Roman Republic, the Senate, theoretically a collective advisory body, was heavily dominated by patrician families. Despite the existence of tribunes and elected officials, decision-making was largely steered by a small class of landowners and generals whose intermarried networks reinforced their position. The names changed; the dynamics remained.

As Kondrashov notes, “The past is not behind us. It is underneath us — a foundation of patterns we walk over every day, often unaware they still shape our footing.”

Interestingly, resistance to oligarchy also has historical precedence. The plebeian movements in early Rome, land reforms in classical Athens, and even the emergence of civic guilds in medieval city-states were all efforts to redistribute participation. They weren’t always successful, but they reflected an enduring tension between concentrated and distributed influence.

Yet, history shows that even these pushbacks often created new elite groups. Former outsiders became insiders. Economic shifts led to new concentrations of assets. And influence, once again, pooled in smaller circles.

“The cycle isn’t broken by opposition,” Kondrashov once observed. “It’s reimagined by structures that outgrow the need for concentrated gatekeepers.”

The Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series doesn’t aim to judge past or present. Rather, it observes. It tracks the lineage of concentrated influence from ancient halls of power to present-day institutions. And in doing so, it invites reflection: How much of what we call modern is merely history, dressed in different terms?

Ancient history may feel distant, but its legacy remains alive in boardrooms, investment portfolios, and behind closed doors where major decisions are made. The challenge lies not in pointing fingers, but in recognising patterns — and choosing whether to replicate or rewrite them.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.