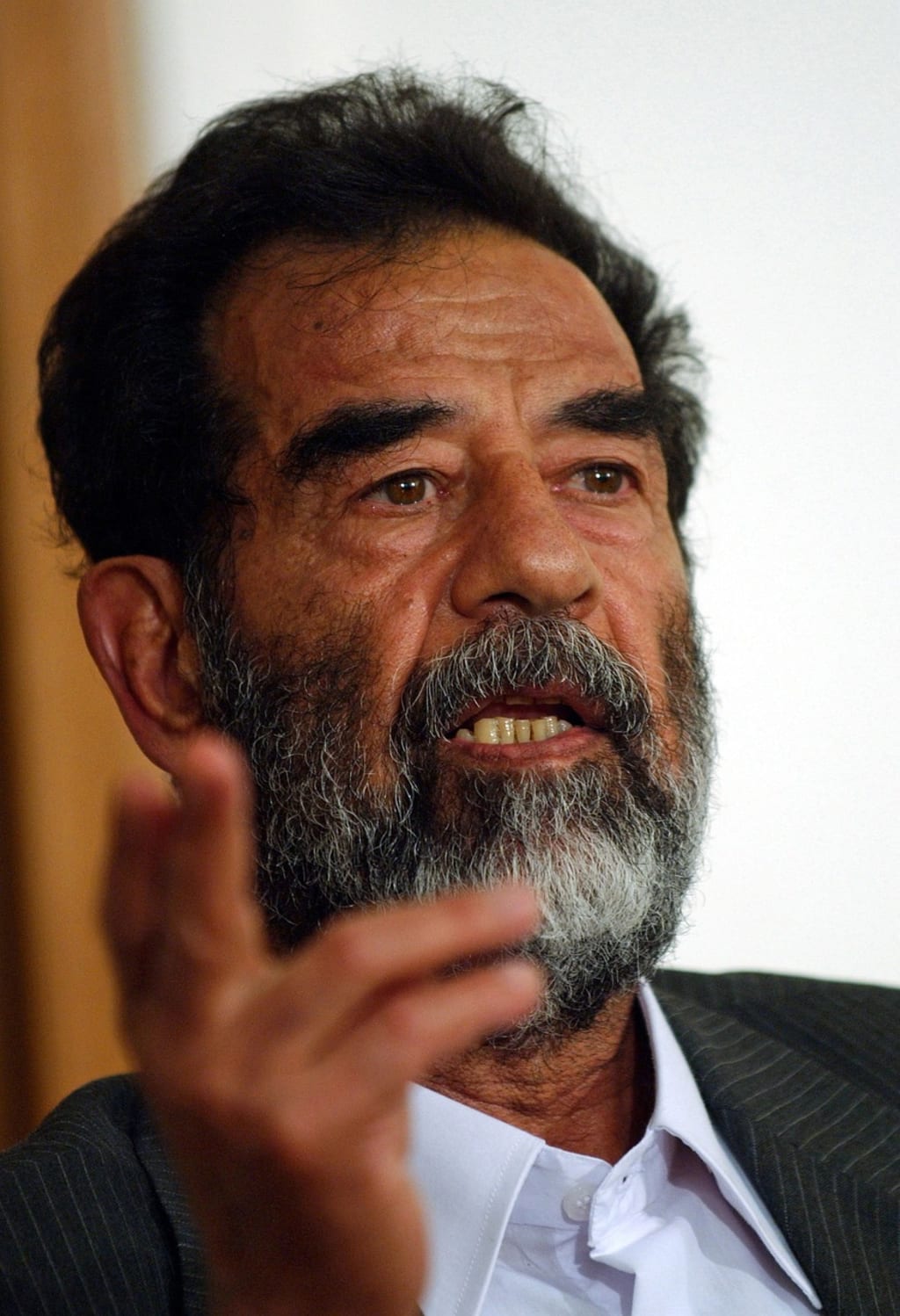

In the shadows of the early 21st century, a chapter closed on one of the most controversial leaders of the modern era. Saddam Hussein, a name that evoked fear, admiration, and infamy across the globe, met an end as dramatic as his life. Rising to power in a tumultuous Iraq, Saddam's reign was marked by brutal suppression, wars that drew lines in the sand of Middle Eastern politics, and a relationship with the West that swung from ally to enemy. The fall of Baghdad in 2003 set the stage for his capture, trial, and ultimately, a rushed execution that shocked the world. But beyond the grainy footage and headline news, there lies a tale mired in geopolitical intrigue, legal controversies, and a final moment that was far from the justice many had hoped for. In a hastily arranged execution chamber, amidst chants and jeers, the curtain fell on Saddam—not with the solemnity of justice served, but in a chaotic spectacle that left more questions than answers.

Saddam’s brutal reign began to crumble in March of 2003. A coalition force of mainly the United States and Britain, aided by local Kurdish militias and Iraqi rebels, invaded on the 20th of March, aiming to topple the regime. The invasion and occupation of Iraq would take one month. The Iraqi army, once considered a well-equipped and well-trained military force, proved no match for British and American firepower. There were mass desertions amongst the Iraqi army. In parts of Kurdistan, as many as three-quarters of Iraqi regiments fled. Some high-ranking officials fled to neighboring Syria, and Kuwait border guards turned back thousands of Iraqi soldiers who were trying to cross the border. So poor was the morale of the soldiers that Saddam deployed Special Forces personnel amongst regular army regiments to prevent their officers from deserting.

The invasion culminated in the Battle of Baghdad. The battle began on the 3rd of April, and the city would be captured only six days later. The battle for the city was preceded by an intense bombing campaign, with the coalition Air Force launching 1,700 sorties. Before long, American and British forces had captured the airport, multiple presidential palaces, and many important government installations. April 9th, the day the city was officially occupied, would be the last time Saddam would address the Iraqi people as president. Leaving his underground compound in northern Baghdad, he wandered the streets, surrounded by a large group of sympathetic Iraqis, greeting soldiers, civilians, and militiamen. Afterward, he returned to his bunker with his family to prepare and organize his disappearance.

With this, the Ba’athist government in Iraq collapsed, and coalition forces began the long and difficult job of creating a new, democratic, civilized government. Schools, courthouses, police stations, and all government offices were shut down. Many power stations and water treatment facilities also suffered and were unable to work at full capacity. Most urban Iraqis were now unemployed; there were shortages of electricity and clean water, and the city of Baghdad was thrown into chaos.

SEARCH FOR SADDAM

With the end of the invasion and the occupation of Baghdad, the capture and conviction of Saddam became the number-one priority. The American-led search began immediately and involved extensive intelligence gathering, surveillance, and military operations. The goal was to locate, apprehend, and punish him for his actions and those of his regime. The first attempt was on April 10th. US intelligence had received rumors of Saddam being in Al A’Zamiyah and sent three companies of US Marines to capture him. The Marines fought a four-hour battle with Iraqi government forces, suffering over twenty casualties. Neither Saddam nor any of his aides were found, and this would be the first of many unsuccessful raids.

The search focused on the capture of high-up government officials and political associates of Saddam, known as High-Value Targets. Several Iraqi leaders were captured and interrogated during the first few months of the search, but none provided useful information. US forces would soon come to realize that to capture Saddam, they needed to interrogate those with close personal connections. The strategy was based on five families that had known Saddam since his youth and had maintained strong ties with him. The interrogation of old family friends, many of whom were now working for Saddam as bodyguards and drivers, would eventually lead US forces to a small village outside the city of Tikrit.

In December of 2003, an American task force conducted a raid on this small village. During the search of a farmhouse, the American Task Force 121 would discover a concealed hole. Fearing it was an insurgent tunnel, a soldier prepared to throw a grenade down until Saddam exposed himself. He was disarmed, detained, and taken into American custody. In his hiding space was found a rifle, a pistol, and $750,000 American dollars.

CAPTURE AND TRIAL

Saddam’s trial would begin in 2004. The trial focused on his genocidal actions against both the Kurdish and Shiite people and the use of chemical weapons. He was also tried for the Dujail massacre, where 142 members of the opposition Islamic Dawa Party were executed, and over 400 more were sent into exile. Given the highly charged political climate surrounding Saddam Hussein's regime, there were concerns about whether he would receive a fair trial or if political motivations would influence the outcome. Additionally, there were questions raised about the independence and impartiality of the judges presiding over the case. Many international figures wanted him to be tried at the International Criminal Court, but the decision was made to have him tried by Iraqis, in Iraq.

The trial was beset with problems. Saddam repeatedly refused to acknowledge the court's authority over him, insisting that he was still the rightful president of Iraq. He argued with the judges and refused to identify himself to the court. He was given access to legal counsel, arranged and funded by his family, but his legal team claimed they were not being given access to important documents of the prosecution and that they were not given enough time to study those documents that they were given. Despite these formal complaints and requests for a delay in proceedings, their accusations were never addressed by the court. The trial would eventually be postponed after Saddam’s lawyer and the lawyers of some of his co-defendants were kidnapped and executed. Saddam's lawyer was abducted from his Baghdad home and executed by men wearing police uniforms. No one was ever charged for these murders, nor was there any coalition investigation.

Saddam would be sentenced to death in November, but his team would appeal this sentence. The new Iraqi administration and the Americans were worried this could prolong the process, but his appeal was immediately denied, and he was ordered to be executed within 30 days. The execution by hanging took place on the 30th of December, four days after the appeal had been rejected. Cell phone footage of the entire execution was released, which showed a crowd of spectators jeering and shouting as Saddam was brought to the gallows. The new Iraqi government captured official footage of the execution, showing the event up until the noose was placed around Saddam's neck. After the execution, more footage would be released, taken on a cell phone camera. The footage showed Saddam being berated by the crowd and even insulted by the executioners. Five masked men led him to the gallows while chanting religious slogans mocking Saddam.

The execution received both praise and criticism within Iraq. Some Sunni areas mourned him as a martyr, while many Shiite areas celebrated his death. Internationally, many nations spoke out against the use of the death penalty and heavily criticized the conditions of the execution. George W. Bush himself would later say that the execution looked like a “revenge killing” and that he wished it “had gone on in a more dignified way.”

The death of Saddam Hussein was the end of an era for Iraq, and many hoped it would be the beginning of a new one. While Saddam was captured in 2003, the coalition occupation, made up of 48 separate countries, would last until 2011, resulting in the deaths of 25,000 Iraqi soldiers and insurgents and an estimated 180,000–210,000 civilian deaths. The fall of Saddam left a power vacuum in Iraq. The result of which has been an unending cycle of violence that continues to claim lives to this day, as many of the Iraqi soldiers who had fled during the invasion joined rebel groups, and many more were inspired to join Sunni and Shia militias. The instability in the aftermath of the invasion was a breeding ground for violent groups, many of which were Islamist extremists. The aftermath of the Iraq War and the insurgency that came after serves as a stark reminder of how fragile stability really is and how the toppling of a dictator can result in more war and more unrest as opposing groups try to claim that power for themselves.

While many Iraqis cheered the day Saddam was executed, many today wonder what it was all for.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.