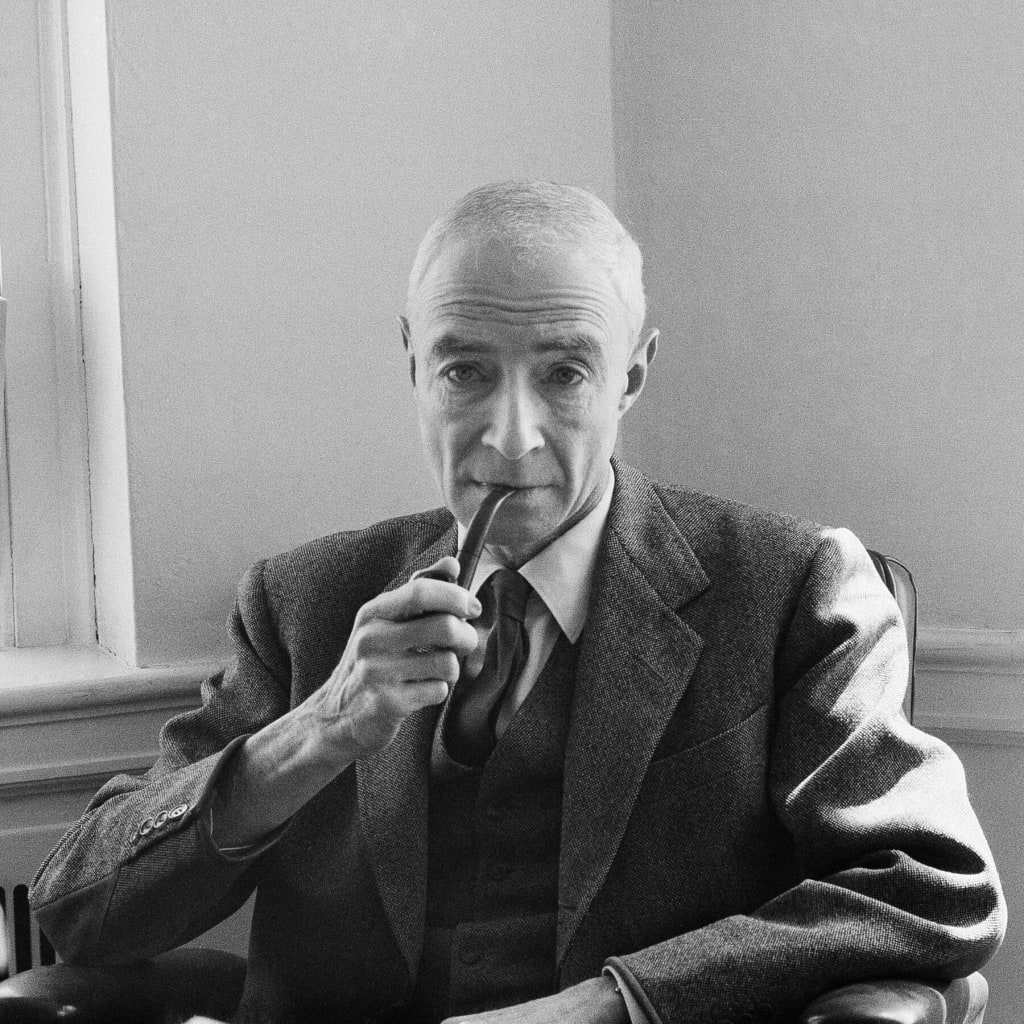

Oppenheimer Why He Deserves a Movie

Oppenheimer was one of the most influential and controversial scientists of the 20th century - and he had a hand in some of history's most important moments.

An introduction to J. Robert Oppenheimer and his lasting influence on the world.

J. Robert Oppenheimer was a brilliant physicist who changed the world more than most Nobel Prize winners. Under his leadership, the best physicists of the 20th century built the atomic bomb, and this led to World War II and the possibility of another world war.

Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize, but he is still considered one of the most important and influential physicists in history. He is responsible for changing the course of history and is likely responsible for all of the wars that have been fought since World War II.

Exploring Oppenheimer's tenure at the University of Göttingen and his flourishing within the realm of theoretical physics.

When J. Robert Oppenheimer was 21, he put an apple laced with toxic chemicals on the desk of his physics tutor. The tutor, Patrick Blackett, was an experimentalist and he had been harassing Robert to do more experimental work. Robert had already been spending his days in a corner of JJ Thompson's basement laboratory, attempting to make thin films of beryllium which were used to study electrons.

Oppenheimer's early engagement in his work appeared to be accompanied by a certain level of uncertainty and avoidance of lab responsibilities. He found himself increasingly drawn to attending lectures and delving into physics journals rather than focusing on his assigned tasks. This occurred around 1925, when Oppenheimer was just 21 years old. During this time, he developed a strong fascination with the emerging realm of quantum mechanics. Despite being in the company of distinguished physicists like Rutherford and Chadwick, Oppenheimer's state of mind was marked by a profound sense of unhappiness.

The impractical tendencies of Oppenheimer and his political associations.

Oppenheimer's lack of prior experience in overseeing such a sizable project became evident. Furthermore, being a theoretical physicist, as highlighted by Isidor Rabi, he was deemed "remarkably impractical" and had limited knowledge about equipment, as stated earlier. The issue of Oppenheimer's political affiliations added another layer of complexity, given his connections to the Communist Party, which also extended to his wife, Catherine, who was a party member. Nevertheless, Groves was deeply impressed by Oppenheimer, placing high value on his unyielding ambition. Groves was aware that Oppenheimer's capacity to comprehend challenges extended beyond the realm of physics, encompassing chemistry, engineering, and metallurgy. This multifaceted ability led Groves to consider Oppenheimer a "genuine genius." Groves noted that Oppenheimer's knowledge spanned a diverse array of subjects, although sports remained an exception. In a lighthearted manner, it was acknowledged that Oppenheimer might not be well-versed in sports. The stark differences between the two men were unmistakable.

The decision to choose Los Alamos as the site for the Manhattan Project.

Oppenheimer's assessment of the forthcoming logistical challenge proved to be significantly underestimated. In 1943, his initial estimation suggested that around six scientists, along with a small team of engineers and technicians, would suffice to develop the bomb. This prediction fell short by a staggering factor of two. The actual workforce for the Manhattan Project would encompass 764 scientists, with 302 of them stationed at the Los Alamos facility.

The magnitude of the endeavor expanded even further when considering that over 600,000 individuals were ultimately involved in the intricate process of crafting the atomic bomb.

Apprehensions surrounding the functionality of the bomb or its potential to exceed expectations.

Around 1942, Oppenheimer and Arthur Compton engaged in discussions concerning a disturbing prospect—a nuclear test with the potential to trigger global catastrophe. The concern stemmed from the possibility that the intense heat generated by the nuclear bomb could lead to fusion, specifically the fusion of hydrogen gas—a minuscule fraction of the atmosphere—due to high temperatures and pressures. This fusion chain reaction could propagate, encompassing not only atmospheric hydrogen but also destabilizing atmospheric nitrogen. Compton recalled these conversations with Oppenheimer in 1959, illustrating Oppenheimer's multifaceted apprehensions.

Most scientists involved recognized the improbability of this scenario, allowing the project to proceed without overly serious consideration of these concerns. However, the idea of initiating fusion through a fission weapon gained significance post-war.

The Trinity test, originally scheduled for 4:00 AM, faced a delay due to adverse weather conditions. Ultimately, at 5:29 and 21 seconds, the world's inaugural nuclear bomb, codenamed "the gadget," detonated. The explosion was ignited by high explosives compressing the plutonium core, generating a shockwave that mixed beryllium and polonium, resulting in a surge of neutrons. This urchin mechanism catalyzed a nuclear reaction, producing an unstoppable explosion. A mere six kilograms of plutonium led to an explosion equivalent to nearly 25,000 tons of TNT. The mountains of New Mexico illuminated, a shockwave reverberated for over 160 kilometers, and a mushroom cloud soared 12 kilometers into the sky. Remarkably hot temperatures fused desert sand into a glassy substance, trinitite. Fortunately, the explosion did not ignite the atmosphere.

On August 6, 1945, the Boeing B29 Flying Fortress dropped "Little Boy," a gun-type nuclear bomb with 64 kilograms of enriched uranium. The nitrocellulose igniting caused uranium-235 slugs to reach their critical mass, resulting in an explosion equivalent to 15,000 tons of TNT. Approximately 70,000 people were killed instantly, and an additional 70,000 suffered from burns and radiation poisoning in the ensuing months. Three days later, an implosion-type bomb similar to "the gadget" was dropped on Nagasaki, causing approximately 80,000 more casualties.

Of the 225,000 lives claimed by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, over 95% were civilians, predominantly women and children. In 1965, reminiscing about the Trinity test, Oppenheimer reflected on a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, expressing a sentiment shared by many involved in the project: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

Following the war, Oppenheimer attained national hero status, his portrait adorning the cover of Time Magazine. In 1947, he assumed the directorship of the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton and chaired the General Advisory Committee, advocating arms control. Despite his opposition, the U.S. developed the hydrogen bomb, triggering an arms race. Oppenheimer's objections led to a security clearance trial, where he was scrutinized for his Communist Party associations and alleged espionage. In 1953, his security clearance was suspended, resulting in media coverage.

In 1964, a play about Oppenheimer's life sparked his displeasure, especially a scene depicting his realization of the sinister nature of his work. Oppenheimer's thoughts on the bombings remained nuanced, acknowledging the complexities of those times. His efforts for nuclear disarmament continued. He passed away in 1967 due to throat cancer, a lifelong smoker.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.