How a Rolex Speedking Linked WWII POWs to Hollywood's Great Escape

Swiss steel behind barbed wire A Gleam

One of the things that the many captured Allied airmen first noticed after the Luftwaffe guards had ransacked their luggage was the complete, practically physical phenomenon of time lack--and in front of the gates wristwatches were seized. But within months packets with the discreet Geneva postmark of Rolex SA began to slither through Red Cross routes into Stalag Luft III and other dozens of camps. New Oyster dials gave something to look forward to and hope: to men who marked their captivity with endless roll calls, the glint of that dial was a reminder that somebody behind the wire still believed they will be free (A Watchful Eye: Rolex and the Allied POWs, 2023).

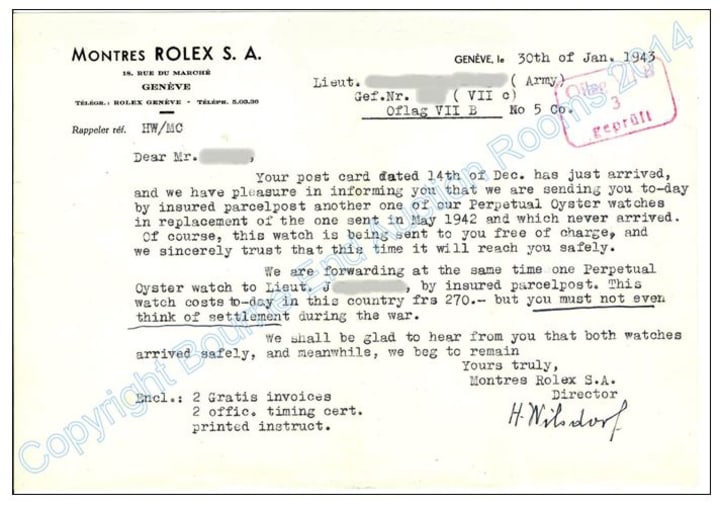

Wartime Gamble of Hans Wilsdorf

The founder of Rolex was neither a soldier nor a saboteur but he knew morale as he knew marketing. In 1940 he made an outstanding promise: any Allied officer was able to order a watch now and pay the bill once the war was won. Delivery was plausible because of Swiss neutrality but not fewer than 3,000 applications followed and all were a possible write-off in case the Reich was able to last. Wilsdorf wrote and signed them, writing, You must not even think of settlement during the war, and this line was soon found on the camp noticeboards (Imperial War Museums Archive, 2024).

Camp Paper Written Promises

In camp newspapers like The Kriegie Times, there could be small boxed advertisements, like the one, found next to chess-problem columns: Rolex Oyster, antimagnetic, pay later. Red cross survivor records reveal entire canvas sacks of parcels marked with the word Horlogerie being taken on to Geneva, to Dulag Luft and by train to individual Stalags. A watch was not the only thing in each parcel, however, there were other things such as replacement mainsprings and any extra screws with a letter of personal enlightenment by Wilsdorf saying that the recipient might have forgotten that in the struggle to find what he was looking for it is worthwhile noting that precision is indeed the enemy of despair. It was quite as good as a pep-talk by London to the prisoners who had to get the rhythm of shifting of tunnels down to the minute (Swiss Federal Postal Records, 1946).

Blueprints of Freedom under the Sand

By the spring of 1943 these borrowed seconds were being hoarded in Hut 104. The repetitiveness echoing like a metronome of the microphones as diggers inched below was described by Paul Brickhill an Australian flier who later became a chronicler as: a watch with it faint beat echoing time and again as a reminder of rebellion. His diaries, in the Imperial War Museums, also mention light discipline: at the stroke of twelve on the second hand of the Oyster, lanterns had to be extinguished so that the watchman above was never aware of the clink of milk-tins during that number of precisely ten breaths (Brickhill Papers, Imperial War Museums, 1945).

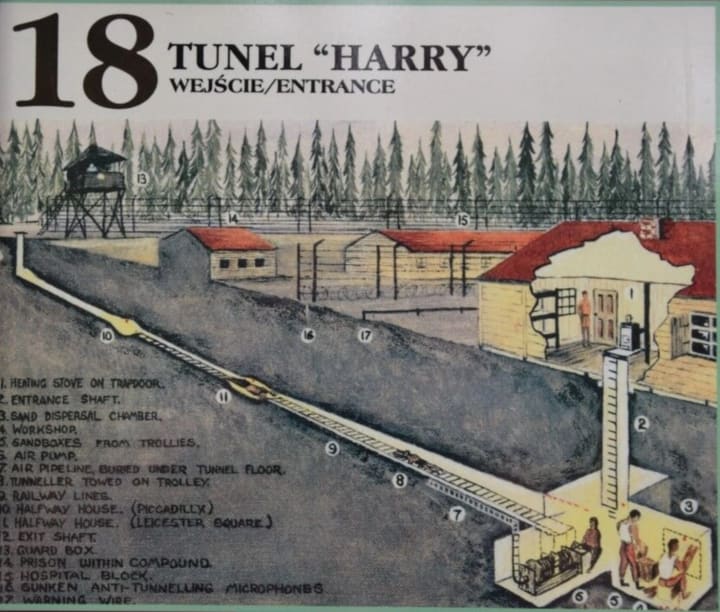

Tunnel Harry Mechanics

Precision mattered. Sand at 30 feet down had at times the power to crush timber in a few seconds and chronographs, as to the duration braces would permit their being sawn out of the bunk slats before their relief was called. Over 1,400 of the Klim milk cans were turned into vent-pipes; 4,000 bed boards were stamped with their numbers and set in position like the ribs of a ship; 1,700 blankets cushioned and muffled every stroke. The Rolexes were both stopwatches and secret payroll: when an engineer had so many shoring feet after 2100 hours he or she received a bonus ration of chocolate (Stalag Luft III Engineering Logs, 1944).

Hitler Fury and Midnight Break

At 22.30, 24 March 1944, the first escapee made the surface short of the treeline--Harry was eight metres short. The rhythm once more was given by watches: one man in 90 seconds until the early morning. Seventy-six crawled to a point when they were observed by a sentry by means of footprints in the frost (The Real Great Escape, 2024). In just 2 weeks the Kripo and Gestapo had retaken seventy-three; fifty were liquidated on the personal order of Hitler, a reprisal which was later condemned at the Nuremberg Trials ( British War Crimes Tribunal Reports, 1947).

A War-Surviving Oyster

The stainless-steel version of the Oyster, referred to as the 3525, which RAF Corporal Clive James Nutting had ordered as a half-finished kit because he wanted the very long strap so that he could conceal the watch in a boot heel during a search as he was a shoemaker. Before Nutting had a chance to test his idea, tunnel Tom collapsed and the reprisal shootings never came. Letters indicate that he wrote to Wilsdorf in 1948 apologising for late payment of as he put it, six years overdue! Rolex responded with a receipt bearing the inscriptions, namely, Paid: gratitudination duly accepted (Rolex Heritage Office, 1948).

Auction Blocks and Afterlives

The Nutting watch reappeared at Antiquorum in 2007 hammering out at 66,000. Since then, the market has picked up: an Oyster 3525, ordered by Wing Cmdr. Douglas Dickins in 1942, sold at Phillips Geneva Watch Auction XVII in 2023 to bring CHF 60,960; with all accompanying POW paper-work, and his flight logs intact (Phillips Geneva Catalog, 2023). What collectors value as much as horology is the provenance of illegally brought in items: the rust to which the dealers refer, as one dealer says, as the patina of barbed wire, adds a fifty grand to the price.

For collectors seeking historically inspired pieces, explore our selection of kaufen uhren that capture the spirit of these iconic timepieces.

When Hollywood kept the legend going

A couple of decades after, Steve McQueen was in need of a period-accurate prop during The Great Escape. He buckled on a rather ordinary Rolex Speedking rather than the more glitzy Submariner worn off-screen, and that was precisely the kind of thing many POWs had ordered, due to the fact that it was low profile and thus easy to conceal. It was just the type of watch that surviving veterans attending the movie premiere in 1963 hoped was displayed (one source related that particular motion picture was squeeky-clean: only that watch was right about the movie) (Los Angeles Times Archive, 1963).

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.