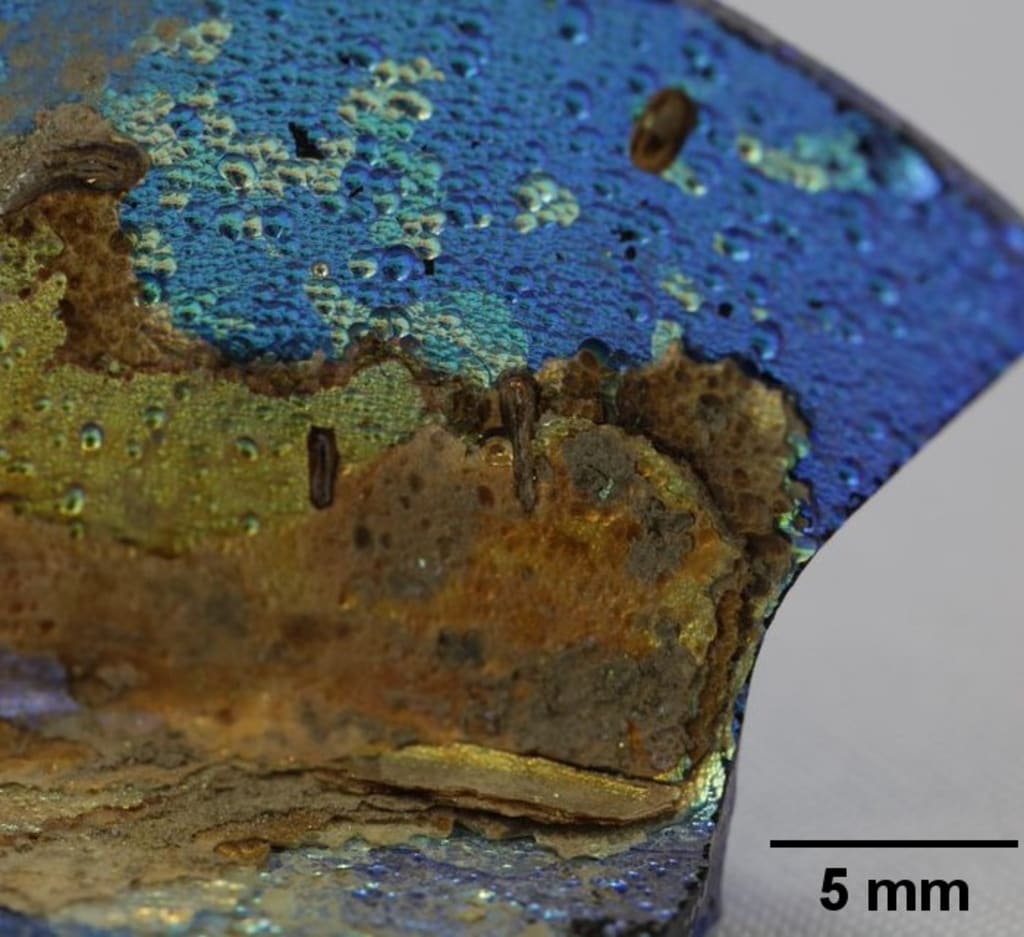

How a Fragment of Roman Glass Transformed into a Photonic Crystal.

The science

Multiple ancient civilizations across the globe, including the Romans. Aquileia, an ancient Roman city, experienced numerous challenges throughout its existence, yet remnants of its past have been revealed by dedicated archaeologists. Recently, an extraordinary discovery emerged in the form of a glass shard found on the outskirts of modern-day Aquileia. This shard, unearthed in 2012, boasts a captivating appearance, showcasing a lustrous blend of deep blue and shiny gold over a rich dark green foundation. Through a thorough examination involving chemical and physical tests, Giulia Guidetti and her colleagues from Tufts University, Massachusetts, have unraveled the mystery behind this remarkable find. The shard's stunning colors are the result of a chemical transformation of the amorphous glass into a nanolayered material, specifically a photonic crystal. This revelation sheds light on the ingenuity and artistic flair of ancient glassmakers, highlighting their ability to create visually mesmerizing pieces. Aquileia's rich history continues to captivate us through the remnants of its past, invigorating our appreciation for the ancient world and its remarkable contributions to human civilization

Glassmaking was concocted freely by a few Bronze Age developments (3300 BCE to 1200 BCE), including those of old Egypt and the Indus Valley. Glass globules, vessels, and dolls remained extravagance things until the Romans concocted the method of glassblowing in the primary century CE. As blowing innovation spread, dishes became less expensive and quicker to create in a more noteworthy assortment of shapes. Things produced in the Roman Realm included containers for beauty care products, containers for sauces, and cups for wine.

Such countless instances of Roman china have endure that Guidetti and her colleagues — which included scientists from the Middle for Social Legacy Innovation in Italy — could assess the date of the Aquileia shard by contrasting its synthetic organization with those of different finds. Its high magnesium and titanium content proposed that the important fixing, sodium-rich sand, came from Egypt and that the glass was made between 100 BCE and 100 CE. The substrate's dull green tone is unique and emerged from the glassmaker's utilization of vegetable debris as a diminishing specialist. The blue and gold tones, nonetheless, emerged later during the debasement interaction.

Substituting layers of low-thickness (dark) and high-thickness (dim) silica are clear in this surface segment imaged with a filtering electron magnifying lens.

To comprehend the beginning of these varieties, Guidetti and her associates analyzed the shard with optical and electron magnifying instruments, finding structures on a few length scales. At the biggest scale are all inclusive inward spaces that are arbitrarily disseminated over the surface, similar to cavities on the Moon. Lined up with the surface are large number of slender layers, generally made of silica, that other in thickness — and consequently refractive file — among high and low. The thickness of the layers diminishes from 320 to 90 nm as the separation from the external surface increments.

The shard's layered design looks like that of a counterfeit photonic gem. In a photonic gem the refractive file is designed to differ occasionally on a length scale equivalent to the frequency of light — that is, two or three hundred nanometers. The periodicity makes obstruction impacts that drop a few frequencies from being reflected back out of the gem. With at least one of its parts hindered, white light that enters a photonic precious stone obtains variety on out.

Comparative impedance impacts produce the shades of the shard. The gleaming gold pieces of the shard's surface owe their reflectivity and variety to the peripheral layers, though the dark blue parts owe their variety to the deepest layers and to the deficiency of the furthest layers. The obstruction impacts depend on frequency as well as the place where light gleams off the surface, with the outcome that the noticed tint changes with survey point. This supposed glow impact is recognizable from butterfly wings and bird feathers (see Expressions and Culture: Pulling out all the stops with Butterfly Wings).

How did such a convoluted construction come to fruition? A critical element is the pH of the dirt that encompassed the shard for the beyond two centuries. Glass opposes acids, however when it's exposed to exceptionally soluble arrangements, the hydroxyl particles respond with the glass' silicon molecules, dissolving the surface to shape pits. The disintegration likewise happens when the arrangement is somewhat antacid, yet it continues gradually sufficient that silicon and oxygen iotas get the opportunity to reprecipitate to shape nanoparticles.

Exactly how those nanoparticles gather into layers was clarified in 2021 by Olivier Schalm of the College of Antwerp, Belgium, and partners [2]. Their urgent understanding was to distinguish the job of a substance input circle that changes the nearby pH of the dirt at the response front. The nearby pH cycles among high and low qualities, leaving afterward substituting layers of inexactly stuffed and thickly pressed silica nanoparticles.

Since the arrangement of the flimsy layers, or "nanolamellae," on the Aquileia shard was driven by their environmental factors, their last construction recommends they developed gradually and consistently without interference for a long time. At the point when Guidetti originally noticed the bunch layers, she was entranced by their magnificence and consistency. Finding so many nanolamellae, so ordinary, consequently very much squeezed is something that you don't see on your typical photonic test, let alone in a trademark photonic one. It appeared to be a disclosure!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.