Margarete sighed, and rested the graver on the bench for a moment.

Remember, this is for your son.

She stretched, but not too far. The leather apron she wore to collect any gold dust from the engraving process was nailed to the bench corners. Crumbs must be collected. No waste in what was left of this guild house!

Which, in the Year of Our Lord 1352, was mostly women.

Plague took the men, and the few that were left were very feeble. Very much not well enough to sit steady at a jeweler's bench for hours on end.

She prayed prayers full of gratitude every day that the horrible sickness that took her husband did not take her last child. They had all gotten sick, but nothing like what she saw happen to her husband. She had nursed all, even when she herself got sick. She had to drag her husband's body from their rooms in the guild hall to the collection cart outside, when it rolled around. At least she'd thought to quickly sew him into their bedsheet. It was from her trousseau that she brought into the marriage, but she could not bear to use it ever again. She would make another, eventually.

The communal kitchen ensured that those who were left still had food to eat. They were very careful with stores now. Farmers were dead by the scores as well, and the least they could do was be good stewards of what remained.

She hadn't eaten well when there was plenty. Too busy taking care of the children, helping her husband, making clothing, buying household supplies. No one remarked upon the wives who helped their husbands with the work, but it happened all the time. Some women would take care of their littles, some would grind glass powder for enamel work. Or work on the wax molds for casting. Her husband is - was - better at the casting, but she had a deft hand for finishing the waxes properly and doing the fine graving work in patterns to set the enamel. They had joked that she should have gotten the Guild Master mark, for her detailed work was much finer than his.

She wasn't laughing now. Three of her children were hopefully in the same unmarked grave with her husband, and the only one left stared at her out of hollowed eyes when they shared the evening meal together in the great hall. He saw what had happened to his father and siblings.

She would never be able to achieve her own personal guild mark, being born a female, but she could hold her husband's in trust for the son that remained. He was young, but in a few years, if he showed some promise, she'd apprentice him herself to show him the joys of working with gold. It was an easy metal, unlike finicky tin or even silver. Heating up the grains and powder she so carefully collected, watching it till it got that particular glow in the crucible, pulling it out with tongs. Pouring it into the lost wax mold, that had been prepared with a mud / manure ratio around the wax they'd carved and and attached wax sprues to, to allow gases to vent out to prevent gaps in the pour. That mold had been dried and turned upside down in the furnace, to allow the wax to melt out.

She'd heard you could carve lead as well, but the wax blend she prepared worked well for her. She would stick with what she knew.

Or maybe her son would take to the enameling. Grinding glass, sifting it, sorting it by how fine it was, filling in the channels and trays they carved and filed into the soft metal.

Or perhaps chasing and repoussé? Using her husband's gravers and chisels, that he had been given by his own father. Carving the gold like it was wax, or scraping details into petals and leaves. Or hammering it from the inside to make details stand out, like grapes and vines.

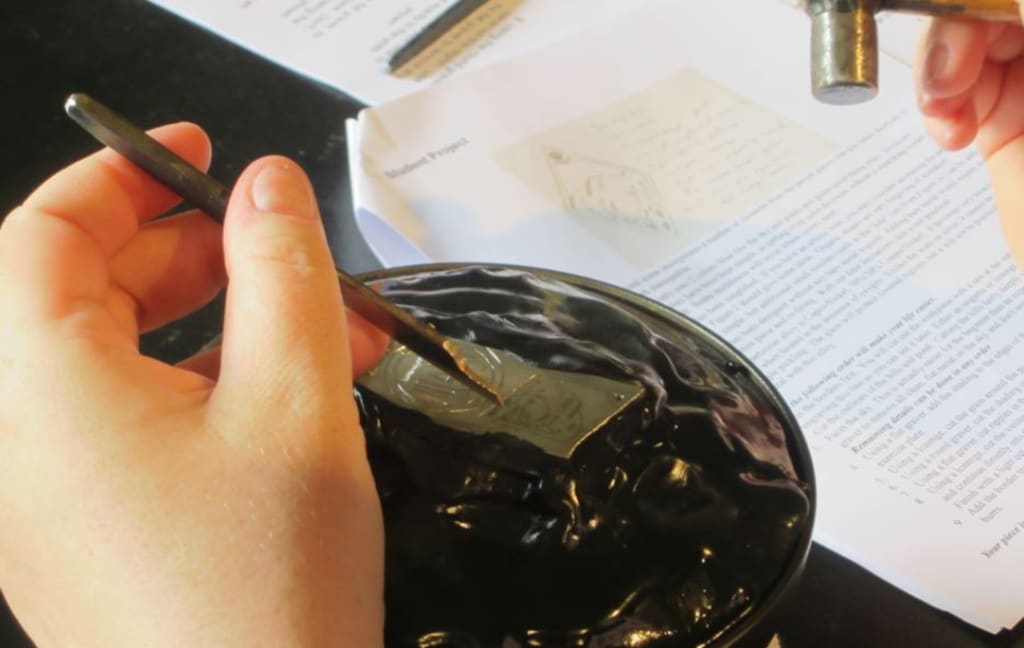

But that was for the future. This belt placket wasn't getting any closer to finishing while she ruminated. The shield element were already in place from the casting, but she wanted to give a pleasing design to the background where she would place the enamel. The colors were transparent, so the pattern would show through.

She had a bit of time. This commission wasn't due for another month, but she always liked to work ahead in case of failure. The enamel could crack, the piece itself could melt as she added the layers of glass paste to melt with the rest. The enamel could chip if not heated and cooled just right as other layers were added. But, God willing, she would be done with the engraving in time for Vespers. They didn't dare venture out into the city yet, and no one was yet allowed in, but they had a decent chapel inside, and could make do without proper services till people stopped dying in waves.

She caught a whiff of the bowl of vinegar she'd set near the fire. It was welcome, unlike the sweet horrid stench of death coming from the entire town. Like the insides of the masks that the plague doctors wore, the bowl contained strong herbs - lavender, rue, wormwood, rosemary. The garlic she should have added was in the kitchen, and would stay for their food. The apothecary suggested the mix, along with staying near fire. If it would keep her and her remaining child safe, she would do it. No one wanted those herbs anyway, though the little meat they got tasted a bit better with some rosemary. The herb garden in the courtyard was looking more than a bit ragged, since so few servants survived. Those few were cooking and cleaning, not tending to useless extra supplies.

They had gruel, with dried fruits, most days, and they were grateful for it. Too many were without even that. And if a chicken wandered in from their pitiful gardens now and again, no one complained. The rest gave eggs occasionally, and only the scrawny ones went in the pot. There were fewer to feed by far, so their stores would last longer.

How anyone of means had the money for the commissions that were still coming, she had no idea. But she was not the only wife of a guild master that helped in the processes, so the women left were assisting each other's work. One would cast, another would engrave, others would watch children or cook or clean. They would trade off the smaller parts, like filing and mold making. Sales from commissions were being held by the guild itself, for a time, till they could figure out a better way.

Anna, their appointed Guildmistress, was sharp. She had helped with the books till her husband, the old Guildmaster, died. There was turmoil as master after master fell to the disease, usually with wives and children following them to the unmarked pits outside the city gates. So many grabbed for the title, only to die soon after. Scarcely had the proper scrolls been inked and sealed, and they were gone. Pretending there was no disease and continuing to host feasts in their hall only led to more deaths than should have happened. Anna put a stop to that, and closed the hall to outsiders. Locked the doors. Now commissions were taken by letter or through a grilled door, and that grille was covered in a double thickness of linen soaked in vinegar with the same herbs that steeped on Margarete's hearth.

Anna kept meticulous notes. Who was left, who did what parts of the labors, how much money was collected, how it was spent. There was plenty of clothing, with all the dead no longer needing them. And everyone was much thinner while recovering from the sickness; not much of an appetite with the memories so fresh. No one cared if they were wearing men's clothing in the work yards, and there were no outsiders to observe.

If felt better to wear linen trousers and shirts, anyway. Even if Margarete ever decided to marry again, she'd already decided it would be on her terms. Her living son would not be pushed away like some reverse-gender Aschenputtel, sitting in the cinders. Little Heinrich would inherit his father's maker's mark, not her new husband, not her new children.

Or - maybe - she would just stay unmarried, and keep it, till her son chose his occupation.

He did show some aptitude for the casting. She taught classes in the morning, for those well enough to learn the craft. A few of the girls were better than the boys; perhaps she should have a talk with Anna about quietly making sure they also had a future in the guild. Anna's goddaughter still lived, and was fair bidding to be just like her. Perhaps they should use all the resources God chose to leave alive. Perhaps she should rethink all of her old thoughts, for the world was completely different now.

She glanced at the sky. The town's church did not have a bell tower, though there had been talk about building one before the sickness came. But the sun's angle told her that it was time to stop woolgathering and get back to work.

She inspected her work. The cross hatching was fine and even. It would look good under the green transparent enamel. She wondered who ordered it, who it was for. It was a lady's girdle placket, but the shield shape was that of a man's. She wondered who might be getting married. She didn't recognize the shield's design, but with so many gone, a strategic marriage would bring many new people into the area. Frankfurt wasn't that far away, and many customers came from all over. Distance gave them a semblence of anonymity sometimes, though the guild master would know all. She wondered if Anna knew.

But, as her late husband said often, "es gut genug." It's good enough. Perfection was for angels, and fussing with a piece would soon lead to disaster. Better to let Anna examine it and approve than to ruin all the work already there. If it needed extra, the others would let her know.

She carefully collected the gold filings from apron and bench, and put them in a waiting crucible. The gravers were gently put back in the proper spots, and the rough belt mounts were brought out with the files. They were cast last week; they'd build a fire hot enough to cast every ten days or so to save wood. Sprue ends and a slight bubbly surface needed to be smoothed. She hated this part, but there were no skilled apprentices left to take the work from her. She felt a sharp pang for what was, and would never be again. She would say an extra prayer for her husband tonight, for all he taught her, to continue.

Like the pieces of gold on her bench, she would survive. For her son.

About the Creator

Meredith Harmon

Mix equal parts anthropologist, biologist, geologist, and artisan, stir and heat in the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch country, sprinkle with a heaping pile of odd life experiences. Half-baked.

Comments (1)

The way you transport us into a different time & place, experiencing it through the thoughts of one particular individual simply doing what they do & knowing what they know, is amazing to me. You recreate entire worlds for us & set us within them. Your skills are remarkable & incredibly well-honed.