Why Many of Your Favorite Redheaded Cartoon Characters Are Actually Black

How Animators Use Red Hair to Mask Black Characters in Animated Worlds

I recently had an epiphany over a friendly debate in a group chat about the race of the characters in A Goofy Movie. You might be thinking “what does it matter what race they are? They’re dogs.” And yes, you are right about them being dogs, but just like with most things in this world, race permeates throughout much of fictional media, including fictional media about cartoon dogs.

This debate started after my annual rewatch of this movie and asking my friends, “What race do y’all think Max is?” For me, the race of these beloved movie characters has always been clear. Goofy is a white man. Maybe the whitest of white men. But his son, Max? That is a biracial boy with a Black mom. As a biracial woman with a Black mom myself, this has been something that I always just intrinsically knew ever since I was a child, even though Max — with his skateboarding and “I hate you” attitude towards his dad — was vastly different from me. But I always just chalked it up to him being raised solely by his white father. And I listed my reasons out to my friends as if I were defending a college dissertation.

- Max’s favorite music artist in the movie is Powerline, an undisputed Black man, voiced by R&B singer Tevin Campbell, modeled after Black artists like Prince, Michael Jackson, and Bobby Brown, has a high top fade with lines etched into the side (a very Black haircut), and his skin is darker than most of the other characters.

- Max’s love interest is Roxanne, a girl who always gave off light-skinned or biracial Black girl vibes to me; she literally looks like my sister.

- We never see Max’s mom in the movie, but Goofy’s love interest in the sequel, Sylvia, is clearly supposed to be a Black woman as well. It may not be obvious in the beginning when she has her hair straightened and is wearing traditional librarian attire, but in the scene where they do the disco number and she’s rocking her afro puff, there’s no denying it. And if Goofy has a type, it’s not far-fetched to think Max’s mother was a Black woman as well.

And probably the most important bit of evidence:

4. Most Black people who are fans of the movie claim this to be an undisputed Black film. How can it be a Black film unless the main character is Black?

The Signs of Blackness In Animation

It’s possible that Max could just be a white boy with a love for Black music and Black women, but as I outlined my argument, I started thinking about the characters I had identified as Black in this movie besides Max (Roxanne and Sylvia) and I realized that the thing these two characters had in common besides their Blackness was that they are both depicted with red hair. And I began to realize that all of the women with red hair in this movie are very Black-coded (just the women because Max’s redheaded homeboy is clearly white). With the other example being Beret Girl, who PJ ends up falling for in the sequel. Beret Girl is depicted with dark red/burgundy hair and is quite Black-coded from her facial features (the full lips and almond-shaped eyes) to being portrayed as a Beatnik. Although a large portion of Beatniks were not Black, the Beatnik subculture was heavily influenced by Black American culture at the time (such as jazz, Black American literature, and lingo like “hip”, “cool”, and “dig”). This often results in Beatnik characters being very Black-coded.

And it is not a coincidence that these three Black-coded characters all share red hair. In fact, I realized that red hair is a semiotic tool that is commonly used when coding non-human cartoon characters as Black.

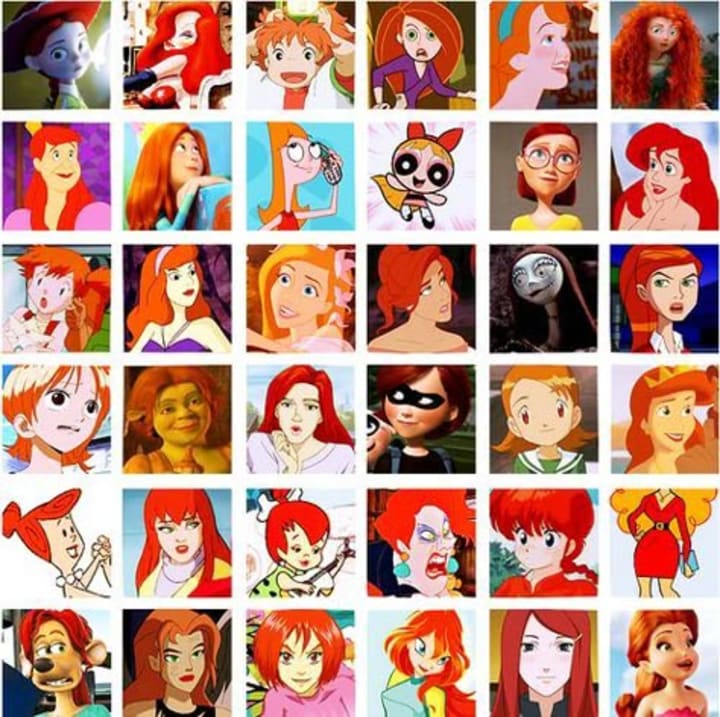

I say this is only really true for non-human cartoon characters because for human characters, red hair is almost always attached to whiteness. Examples like Chucky Finster from Rugrats, Kim Possible, Blossom from Powerpuff Girls, or Merida from Brave show that perfectly.

But for non-human characters, red hair serves a specific purpose. Since these characters don’t have a literal race, animators can play with cultural coding: red hair gives them a marker of difference or “otherness” — enough to signal minority status — allowing writers and actors to project Black-coded traits onto them, while simultaneously giving these characters enough ambiguity that viewers could still interpret them as white if they wanted to. It’s like a visual compromise: the character is visibly distinct, but not explicitly human, so the creators can imbue them with Black-coded behaviors, speech patterns, attitudes, or experiences without directly depicting a Black person.

Let’s look at some examples:

Simba & Mufasa (The Lion King)

This is probably the easiest example to justify. Mufasa is literally voiced by Black actor, James Earl Jones, and the movie is set in East Africa. And although Simba is voiced by white actors, both as a child and an adult, this isn’t anything new. Throughout history, Hollywood has often used white actors to depict non-white characters, and this is no exception. If Simba were a human, he would definitely look more like Daniel Kaluuya than Jonathan Taylor Thomas.

Elmo (Sesame Street)

Elmo being a Black character has become a very widely accepted idea by many Black people who grew up watching Sesame Street. Since the very beginning, Sesame Street was already a show that really worked to cater to Black and brown children, with the setting even being modeled after neighborhoods in Harlem, New York City (a largely Black and Latino area). And with Elmo being one of the original characters on the show, he took on a lot of very Black-coded attitudes and mannerisms.

His ongoing beef with the pet rock character, Rocco, is one that often reads as the kind of exasperated, comedic commentary you’d hear from a Black child who is tired of people gaslighting him. Elmo is also often seen dancing and doing things with music, something that is very important to many Black children. He has even been featured in musical numbers on the show with several Black artists like Usher, India Arie, Patti Labelle, and Destiny’s Child. And on Juneteenth of this year, Sesame Street basically confirmed that Elmo is Black when they posted a Happy Juneteenth picture on their official Instagram page, featuring canonically Black characters, Gabrielle and Tamir, and then including the characters Abby and finally, Elmo himself.

Aku Aku & Uka Uka (Crash Bandicoot games)

These twin brothers are the guiding forces behind the protagonist of the video game series (Crash Bandicoot) and the main antagonist (Dr. Neo Cortex) and are canonically the human spirits of two witch doctors who were placed inside of these voodoo masks. Aku Aku is depicted with multicolored feathers on his head and a green leaf goatee, but what color are his eyebrows? That’s right. Red. And his evil twin brother, Uka Uka? His beard and eyebrows are also red. Being that these two characters were designed to mirror the traditional masks of Aboriginal Australians, it is not hard to deduce that in their human lives, these brothers were themselves, Black Aboriginals.

Oliver & Dodger (Oliver and Company)

Based on the Charles Dickens novel, Oliver Twist, Oliver and Company is an underrated Disney classic from the 80s. Growing up, it was one of my all-time favorite movies and now I see that a big reason was probably because, much like with A Goofy Movie, it felt very Black.

The movie opens up with a wideshot of New York City and then we zoom in to a box of kittens being sold on the sidewalk. Most of the kittens in this box are typical neutral colors (brown, white, grey) but we see one kitten that is bright orange; Oliver. And surprise, surprise, he’s the only one who ends up not being adopted. This is very similar to how in the American foster system, Black children are the least likely to be adopted. We then have Oliver being forced into street survival and taken in by a group of dogs who get by through crime and he has to navigate a city that wasn’t built for him. This echoes themes seen in many stories about young Black boys or children of color who must find chosen family and survive systems that overlook them.

Not only is Oliver Black-coded, but his mentor, Dodger, is also Black-coded. Dodger is a dog whose fur is primarily white except for a patch on his back and the fur on the top half of his head. Can you guess what color that fur is? Ding ding ding! If you said red/orange, you’re correct. But Dodger is voiced by a white man, Billy Joel. However, Billy Joel plays Dodger as a street-wise, swaggering cool guy that Oliver is in awe of, and when he sings his song “Why Should I Worry?” he doesn’t sing it in typical Billy Joel “Piano Man” fashion; he sings it with a more gritty, soulful, even funky energy — more Ray Charles-esque than classic Billy Joel. The way he sings, the way he moves, even the cadence in which he talks, all give him the energy of a smooth-talking character that wouldn’t be out of place in a Blaxploitation film.

And we see with the other members of Dodger’s gang that the creators were okay with writing characters to be explicitly non-white: Tito is a chihuahua with a Chicano accent voiced by Cheech Marin and Rita is a brown soulful dog with blue eyeshadow voiced by Sheryl Lee Ralph. But these characters are not main characters, which means that making them explicitly Chicano or Black, does not mark the movie itself as a “Black movie,” the way that it would have if the main characters, Oliver and Dodger, were. This is why Oliver and Dodger (and many other characters) may not have been allowed to explicitly be Black, but are allowed to feel Black.

Even characters without hair or fur can be subject to this color coding. When they have no hair to be colored red, animators will often settle for making the whole character red or orange instead. These characters aren’t technically redheads, yet they visually occupy the same color space, reinforcing the link between fiery tones and Blackness. Think Mushu from Mulan, a red dragon who is not just voiced by Eddie Murphy but whose entire characterization is modeled after his comedy. Or Darwin from The Amazing World of Gumball, an orange fish who is voiced by a Black actor and is clearly adopted, being that he is an entirely different color and species than the rest of his family. Or Sebastian from The Little Mermaid, a bright red singing crab who speaks in metaphors and has a Jamaican accent. Or even Wilt from Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends: the red basketball-playing imaginary friend, named after Black NBA legend, Wilt Chamberlain.

Black People & Redheads: Two Sides of the Same Coin

The connection between Black people and redheads has always been prevalent in the media and is something that has been analyzed for years. Many people have dissected the Black protagonist and redheaded best friend trope in media (and vice versa). Think Raven & Chelsea from That’s So Raven, Kim & Monique from Kim Possible, Penny Proud & Zoey from The Proud Family, Rocky Blue & Cece Jones from Shake It Up, Kim & Stevie from The Parkers, even Barbara Howard & Melissa Schemmenti from Abbott Elementary. More recently, there’s even been the trending idea online that gingers are the “Black people of the white community.”

Then there’s the phenomenon where redheaded cartoon characters are race-bent to be portrayed by Black characters in live-action versions. This most likely occurs because redheads have always sat at the edge of whiteness: culturally white, yes, but often marked as different. Red hair is extremely rare, with only about 1% to 2% of people possessing it naturally. It is also often associated with people of Irish descent, and historically, the Irish were often discriminated against in the United States — having once been indentured servants, persecuted for their Catholic faith, and being overlooked for jobs for a good chunk of American history. And in the twenty-first century, we still see remnants of this otherness that redheads are embedded with through things like jokes about gingers having no souls.

In other words, redheads are one of the closest things to a minority within whiteness. So when Hollywood wants to diversify a story without touching characters that are too core white, who usually gets chosen first? The white characters who were already depicted as slightly outside the norm i.e., the redheads.

There are plenty of examples:

- Little Orphan Annie (white in both the comic strip and original movie adaptation) → played by Quvenzhané Wallis in the 2014 version

- Mary Jane “MJ” Watson from Spiderman (white in the comics and most movie adaptations) → portrayed by Zendaya in recent movie adaptations

- Ariel from The Little Mermaid (white in the 1989 Disney animated movie) → portrayed by Halle Bailey in the 2023 live-action remake

Whenever this happens, some fans lose their minds. But the irony is this: The important part of the redheaded characters they’re gatekeeping was never their whiteness, but their otherness. The red hair is often just a means of showing their difference, outsider status, misunderstood identity, or social marginalization.

This is why, when swarms of people get bent out of shape about a redheaded cartoon mermaid being played by a Black actress in the live-action remake, they have missed the point entirely. Ariel’s whiteness was never the core of her character. She was always meant to stand out, to be marked as different, as rare, as an outsider. And if “visibly other” is the goal, who better to embody that than a Black actress in a cast that primarily consists of white people?

Conclusion

At the end of the day, none of this is about proving that a cartoon cat or puppet or lion is literally Black. It’s about recognizing how race coding has always shaped the way we create and interpret stories, even when those stories are told through animals, mermaids, monsters, or talking masks. Animators rely on shorthand to signal identity, and audiences pick up on those signals whether they realize it or not. So when you start noticing the patterns — the red hair, the orange fur, the soulful voice, the cultural references — it becomes obvious that these characters were never raceless; they were just coded in ways subtle enough to slip under the radar.

And that’s what makes the uproar around race-bent adaptations so ironic. People insist they’re “just staying true to the original,” but half the time, the original character was already drawing from minority experiences to begin with. What we’re really seeing is a discomfort with acknowledging the Blackness that was always there, hidden in plain sight. Because once you recognize how often “redhead” has functioned as a stand-in for “other,” it becomes impossible to unsee how naturally and how seamlessly Blackness fits into these roles. And honestly? The stories are richer, truer, and far more interesting once you finally name the thing the media has been winking at for decades.

-------------------------------------------

If you found this to be interesting, go ahead and hit the follow button.

Are there any other Black-coded characters you can think of that follow this red/orange color scheme? Let me know in the comments.

And before you get in the comments saying something along the lines of “it’s not that deep,” ask yourself if it’s truly not that deep, or if you’re just not that deep.

Thanks for reading!

About the Creator

C.R. Hughes

I write things sometimes. Tips are always appreciated.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.