Why Gorky Park (1983) Feels So Cold — and Why That Coldness Matters

When Hollywood tried to translate Cold War dread from the page to the screen things turned cold in more ways than one.

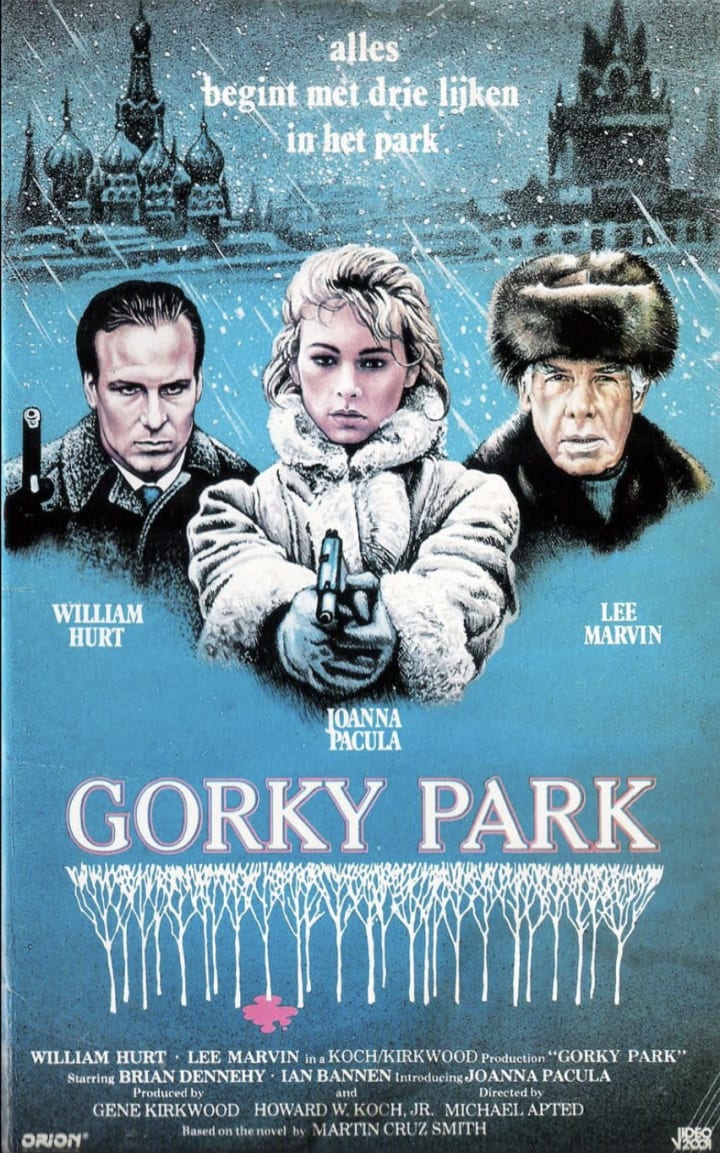

Gorky Park

Release Year: 1983

Director: Michael Apted

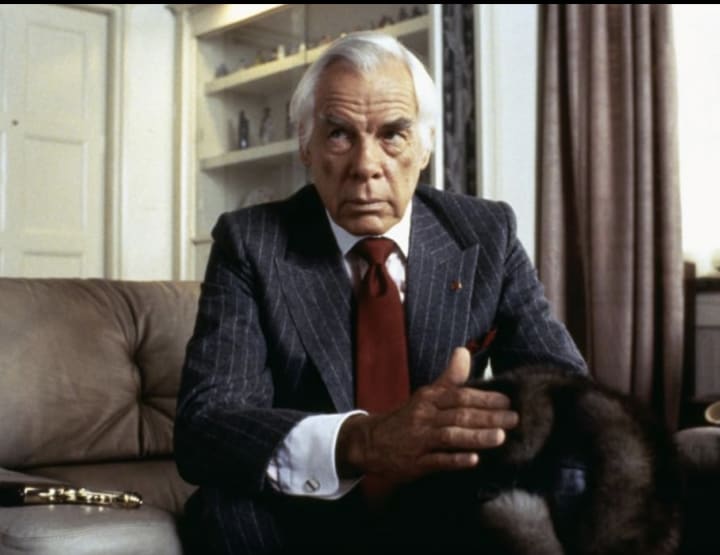

Starring: William Hurt, Lee Marvin, Joanna Pacuła

3 out of 5 stars

Rewatching Gorky Park now, what strikes me most isn’t the mystery, or even the politics. It’s the temperature.

This is a cold movie. Emotionally distant. Quiet. Restrained to the point of discomfort. And it’s easy to see why that chill left audiences uncertain back in 1983, when American movies about the Cold War tended to be loud, declarative, and morally certain.

Gorky Park isn’t interested in certainty. It doesn’t reach out to reassure you. It watches from a distance and expects you to lean in.

That quality has often been mistaken for failure. Revisiting it today, it feels more like intent.

What Struck Me This Time

The film opens with a grotesque image — three mutilated bodies discovered in Moscow’s most famous park — yet the direction immediately undercuts any expectation of a conventional thriller.

There’s no rush. No procedural snap. No charismatic detective laying out the rules of the game.

Instead, Michael Apted lets the moment sit in silence, surrounded by snow, concrete, and bureaucracy. The horror isn’t stylized. It’s bureaucratic. The crime doesn’t feel shocking so much as inevitable.

That tone never really changes.

What stayed with me on this viewing was how often Gorky Park resists giving the audience emotional access. Scenes end early. Conversations trail off. Important moments happen offscreen or are treated with deliberate understatement.

This is not an accident. It’s the film’s defining choice.

A Hero Who Keeps Everything Inside

William Hurt’s Arkady Renko is one of the most withholding protagonists of the decade.

He doesn’t explain himself. He doesn’t give speeches. He rarely lets emotion surface in ways an American audience might expect. Hurt plays Renko as a man who has learned that visibility is dangerous.

Watching him now, I was struck by how little the film asks us to like him — and how much it asks us to observe him.

Renko doesn’t chase justice in the traditional sense. He endures. He navigates power structures he doesn’t control. He survives by being patient, careful, and inward.

In another era, that might read as passivity. In the context of the film, it feels like realism.

A Studio Film Afraid of Absolutes

One reason Gorky Park feels so restrained is that it’s clearly a studio film wrestling with uncomfortable material.

Set deep inside the Soviet Union, the movie refuses to reduce its world to easy villains or patriotic shorthand. Corruption exists everywhere. Power is fluid. Morality bends depending on who is watching.

At the same time, the film never fully commits to outright cynicism. It gestures toward moral ambiguity, then pulls back.

Watching it now, that tension feels less like cowardice and more like the limits of what a mainstream American release could openly say in 1983.

The Cold War is present in every frame, but it’s rarely spoken aloud. It hangs in the air instead — an unspoken pressure shaping every interaction.

Mood as Meaning

James Horner’s score and Apted’s visual control do a lot of the film’s heavy lifting.

Snow-covered streets. Stark interiors. Faces framed at a distance. The camera rarely invites intimacy. When it does, it feels earned — and fleeting.

The result is a movie that communicates theme through atmosphere rather than dialogue. You don’t need to be told that truth is dangerous here. You feel it.

That approach may explain why Gorky Park has never been a comfort watch. It doesn’t build toward catharsis. It builds toward acceptance.

Why the Ending Doesn’t Comfort

By the time the film reaches its conclusion, it becomes clear that Gorky Park isn’t interested in triumph.

There is resolution, but not relief. Survival replaces victory. The system remains intact. The damage lingers.

What struck me most this time was how little the film tries to soften that reality. It offers just enough closure to end the story, then steps away.

In the context of early-’80s American cinema, that restraint feels almost defiant.

Final Thoughts: A Film Out of Step — On Purpose

Gorky Park didn’t fail because it misunderstood its audience.

It failed because it refused to meet that audience halfway.

In a decade defined by clarity and conviction, this was a film built on doubt, distance, and quiet endurance. Its coldness wasn’t a flaw — it was the point.

Revisiting it now, that chill feels less like a problem and more like a warning.

Some stories aren’t meant to reassure.

They’re meant to linger.

Subscribe to Movies of the 80s here on Vocal and on YouTube for more 80s Movie Nostalgia.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.