Shakespeare's London

How Elizabethan England Shaped His Plays

Background and Context:

I’m eventually going to stop explaining myself but here’s what it is for those of you who don’t know. I’ve found tons of essay ideas for essays that were never written on my laptop, in notebooks and on my notes application and I’ve decided to write them. So, check back for more soon and well, I’ve already written some so there’s that. You may notice that there are trends in terms of the reading and I implore you not to skip out on the secondary sources. There’s some good stuff in there!

Shakespeare’s London

How Elizabethan England Shaped His Plays

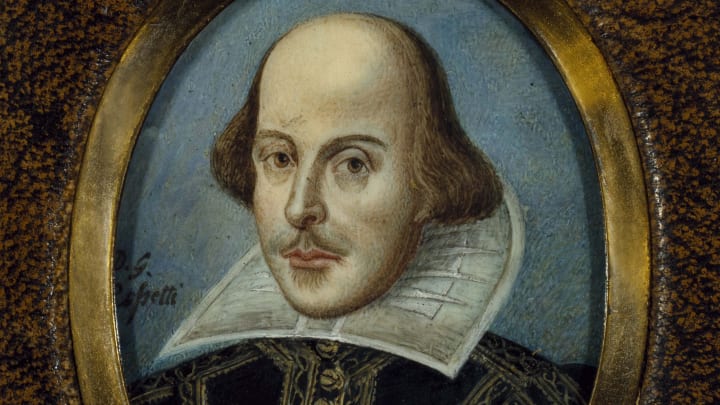

William Shakespeare was not only a masterful playwright but also a keen observer of the world around him. His works, spanning histories, tragedies and comedies, reflect the political, social, and cultural realities of Elizabethan London. Living and working in a rapidly expanding city, Shakespeare was immersed in an environment of political intrigue, economic change, and artistic flourishing. His plays therefore, were not created in isolation; they were deeply shaped by the concerns, beliefs, and tensions of his time.

Elizabethan London was a city of contrasts. While it was a hub of intellectual and artistic innovation, it was also rife with poverty, disease, and social unrest. London’s population had grown exponentially. It began attracting merchants, actors, and playwrights, while also suffering from overcrowding and outbreaks of plague (Ackroyd, 2006). Theatres such as The Globe became central to public entertainment, bringing together audiences from different social classes, from aristocrats to the ‘groundlings’ who stood in the pit (Gurr, 1996). This diverse audience meant that Shakespeare had to appeal to both the educated elite and the working poor, which is evident in his mixture of high poetry and bawdy humour.

Also, Shakespeare’s work was influenced by the political landscape of Elizabethan England. Under Queen Elizabeth I, England had established itself as a Protestant power following years of religious turmoil. The doctrine of the ‘divine right of kings’ was reinforced, shaping the themes of legitimacy, power, and treachery in plays such as Macbeth and Richard II (Greenblatt, 2004). At the same time, the fear of political conspiracies, fuelled by events such as the Babington Plot (1586), found echoes in Hamlet and Julius Caesar.

The Political Climate

Shakespeare’s plays were deeply influenced by the political landscape of Elizabethan England. The late 16th century was a time of relative stability under Queen Elizabeth I, but it was also a period marked by anxieties over succession, fears of political conspiracy, and strict government control over public discourse. Shakespeare, writing in this climate, had to navigate these tensions carefully, often using historical or foreign settings to explore themes of power, legitimacy, and rebellion.

Elizabeth I ascended the throne in 1558 following a period of intense religious and political turmoil under her predecessors, Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Mary I. Her reign, often celebrated as a ‘Golden Age’, brought a level of stability after years of Protestant-Catholic conflict, but the question of succession loomed large since Elizabeth never married or produced an heir (Guy, 2016). This uncertainty is reflected in Shakespeare’s history plays, where questions of rightful rule and the consequences of weak or disputed leadership are central themes. Richard II, for example, explores the deposition of a legitimate monarch, a subject that would have resonated in an era when stability depended on strong leadership.

The concept of the divine right of kings, which held that monarchs were God’s appointed rulers, was reinforced during Elizabeth’s reign and continued under James I. This ideology is powerfully interrogated in Shakespeare’s plays, particularly in Macbeth and Richard II. In Macbeth, the disruption of legitimate rule through regicide leads to chaos, famine, and unnatural occurrences, reinforcing the belief that rebellion against the monarch is an affront to divine order (Dollimore, 1984). Similarly, Richard II presents the downfall of a king who, though weak, still embodies the sacred authority of monarchy. These plays reflect contemporary fears of political instability while also subtly questioning the consequences of absolute power.

The Elizabethan government exercised strict control over public speech and theatrical productions, particularly when it came to politically sensitive subjects. The Master of the Revels, an official responsible for approving plays, could censor works that were seen as seditious or disrespectful to the monarchy (Dutton, 1991). Shakespeare, like his contemporaries, had to tread carefully, especially when depicting the overthrow of rulers or political conspiracies.

To avoid direct criticism of the English monarchy, Shakespeare often set his plays in the distant past or foreign lands. Julius Caesar, for instance, explores the assassination of a ruler and the chaos that follows, mirroring Elizabethan fears about political rebellion, but safely contained within ancient Rome (Greenblatt, 2004). Similarly, Hamlet addresses themes of corruption and the abuse of power in the Danish court, rather than an English one, allowing Shakespeare to explore contemporary anxieties without inviting royal censure.

Although there were these constraints, Shakespeare’s plays offer profound insights into power and governance, reflecting the political concerns of his time while engaging audiences in debates that remain relevant today.

The Social Landscape

Shakespeare’s London was a city of rapid expansion, social contrasts, and recurring outbreaks of disease. The urban landscape was shaped by a widening gap between rich and poor, an ever-present threat of plague, and the thriving world of theatre. These social realities found their way into Shakespeare’s plays, where he explored themes of social hierarchy, human suffering, and the communal experience of theatre.

By the late 16th century, London’s population had surged to nearly 200,000, making it one of the largest cities in Europe (Porter, 2000). This growth brought economic opportunities but also extreme poverty, crime, and overcrowding. The city was home to both aristocrats and destitute beggars, a contrast that Shakespeare frequently dramatised. King Lear, for instance, powerfully exposes the divide between wealth and poverty; Lear, once a king, is reduced to a state of wretchedness, realising too late the plight of the poor: “Poor naked wretches, whereso'er you are, / That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm” (Shakespeare, King Lear, 3.4.28–29). Shakespeare’s plays also reflect the tensions between the rising middle class, the nobility, and those on the fringes of society. Characters such as Malvolio in Twelfth Night embody the ambitions of social climbers, while figures like Falstaff in Henry IV Part 1 celebrate the rowdy, rebellious spirit of the lower classes.

London’s rapid expansion made it particularly vulnerable to disease, and outbreaks of the plague were frequent and devastating. Theatres were often the first public spaces to be closed during epidemics, including significant closures in 1592–1594 and again in 1603 (Bellingham, 2018). During these periods, Shakespeare and his company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, had to find alternative ways to earn a living, often touring the provinces. The instability caused by the plague influenced Shakespeare’s writing, with recurring themes of fate, death, and the fragility of human life appearing in plays such as Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet.

Despite these hardships, the theatre remained at the heart of London’s cultural life. The Globe Theatre, where many of Shakespeare’s plays were performed, attracted a diverse audience. The wealthier elite could pay for seating in the galleries, while the ‘groundlings’ (ordinary citizens who paid a penny for standing space) filled the pit (Gurr, 1996). This mix of social classes meant that Shakespeare had to craft his plays to appeal to all levels of society. His works combined poetic soliloquies and political intrigue for educated audiences with bawdy humour and action-packed scenes for the common people. Theatre was not just a form of entertainment but a shared social experience, one that reflected the concerns and aspirations of its audience. Shakespeare, as both a playwright and businessman, understood how to engage this diverse public, ensuring that his works resonated with both the elite and the everyday Londoner.

Religious Partition

Shakespeare lived in a period of intense religious upheaval and widespread belief in the supernatural. England’s shift from Catholicism to Protestantism under Henry VIII and the continuing tensions under Elizabeth I and James I created a world in which religious allegiances were both politically dangerous and socially divisive. At the same time, superstition played a significant role in everyday life, with widespread belief in witches, ghosts, and omens. Shakespeare’s plays reflect these preoccupations, subtly engaging with religious tensions and exploring the supernatural as a means of questioning fate, morality, and human agency.

Although England was officially Protestant under Elizabeth I, many Catholics remained loyal to the old faith, leading to government suspicion, persecution, and rebellion (Haigh, 1993). Shakespeare himself came from a Catholic family; his father, John Shakespeare, was fined for not attending Protestant services, but he carefully avoided overtly religious polemics in his plays (Greenblatt, 2004). Nevertheless, the anxieties of religious conflict permeate his work.

In Hamlet, the ghost of King Hamlet is a striking reference to Catholic doctrine. The ghost describes himself as trapped in purgatory, a Catholic belief that Protestants rejected: “I am thy father’s spirit, / Doomed for a certain term to walk the night” (Hamlet, 1.5.9–10). This moment reflects the religious uncertainty of the time, if purgatory does not exist, then what is the ghost? Is it a genuine spirit or a demonic deception? Hamlet’s struggle with doubt and inaction mirrors the theological confusion of an age caught between two competing faiths.

Similar to this, Measure for Measure explores issues of morality and sin through a distinctly religious lens. The play’s themes of justice, mercy, and sexual transgression echo contemporary debates about Protestant strictness versus Catholic forgiveness (Dutton, 2016). Duke Vincentio’s disguise as a friar, and the play’s focus on confession and repentance, suggest a Catholic framework, yet the resolution leans towards Protestant ideals of state-controlled morality.

The Elizabethans believed in supernatural forces, and this belief shaped Shakespeare’s portrayal of fate, destiny, and human folly. In Macbeth, the witches embody contemporary fears about witchcraft, which was considered a real and dangerous force. The play was written in the early years of James I’s reign, a king notorious for his obsession with witches; his book Daemonologie (1597) reinforced the idea that witches conspired with the devil to manipulate human affairs (Purkiss, 2007). The witches’ cryptic prophecies: “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” (Macbeth, 1.1.12), lead Macbeth to believe he is fated for greatness, but their ambiguity ultimately leads to his downfall, reinforcing the notion that tampering with supernatural knowledge is perilous.

However, A Midsummer Night’s Dream presents the supernatural in a playful, enchanting manner. The fairies, led by Oberon and Titania, interfere with human lives, causing confusion and chaos. Yet, unlike Macbeth, their magic is ultimately benign, reflecting the lighter side of Elizabethan superstition, the belief in spirits who could bless or trouble human affairs. Through both religious and supernatural themes, Shakespeare engaged with his audience’s deepest anxieties and beliefs, creating plays that resonate with the tensions of his time while exploring universal questions about morality, fate, and the unknown.

Global Ambition

During Shakespeare’s lifetime, England was emerging as a significant player on the global stage. The late 16th and early 17th centuries, often referred to as the Age of Exploration, saw the expansion of English naval power, increased trade with distant lands, and the beginnings of colonial ambitions. These developments shaped English attitudes towards foreign cultures, race, and national identity, attitudes that Shakespeare reflected and interrogated in his plays. Works such as The Tempest, Othello, and The Merchant of Venice engage with themes of exploration, colonialism, and xenophobia, revealing both admiration for the wider world and deep-seated anxieties about cultural difference.

England’s growing interest in overseas exploration was driven by figures such as Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Francis Drake, who led expeditions to the Americas and challenged Spanish dominance at sea (Armitage, 2000). The fascination with new lands and peoples is reflected in The Tempest, which many scholars interpret as Shakespeare’s response to England’s colonial ambitions. Prospero’s arrival on the island, his dominance over the native Caliban, and his claim to rule reflect the attitudes of European explorers who viewed indigenous peoples as subjects to be controlled and ‘civilised’ (Vaughan and Vaughan, 1991). Caliban’s bitter words: “This island’s mine, by Sycorax my mother, / Which thou tak’st from me” (The Tempest, 1.2.331–332), echo the real-world tensions between European settlers and indigenous populations.

In Othello, the theme of global expansion is reflected through the play’s setting in Venice and Cyprus, both key trading centres in the Mediterranean. Othello himself, a Moor in Venetian service, represents the complex role of foreign individuals in European society, valued for their military skill yet viewed with suspicion and racial prejudice (Bartels, 2008). His status as an outsider in Venetian society parallels England’s own cautious engagement with foreign cultures in an era of expanding trade networks.

Shakespeare’s portrayal of foreign characters often reflects the tensions of an increasingly interconnected world. Othello is perhaps his most striking exploration of racial identity, depicting a Black protagonist who rises to prominence in a white-dominated society. However, despite his military success and noble character, Othello is persistently othered, referred to as “the Moor” rather than by his name, and subjected to racist slurs such as Iago’s description of him as “an old black ram” (Othello, 1.1.88). His ultimate downfall at the hands of Iago can be read as an indictment of a society that, despite his achievements, never fully accepts him.

Also, The Merchant of Venice examines xenophobia through the character of Shylock, a Jewish moneylender in a deeply anti-Semitic society. While Shylock is presented with negative stereotypes, Shakespeare also gives him a voice to challenge discrimination, most famously in his speech: “Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions?” (The Merchant of Venice, 3.1.49–51). This dual portrayal, both reinforcing and critiquing stereotypes, reflects England’s conflicted attitudes towards outsiders, shaped by religious intolerance and economic rivalry.

Through these plays, Shakespeare captured the anxieties and aspirations of an England increasingly engaged with the wider world. His works both reflect and challenge contemporary attitudes towards exploration, colonialism, and cultural difference, making them deeply relevant to discussions of global identity and power.

Literary Influences

Shakespeare’s works played a pivotal role in shaping the English language and literary tradition. Writing at a time when English was gaining prominence as a literary language, Shakespeare expanded its expressive possibilities, introducing new words, phrases, and poetic techniques. His engagement with classical sources and contemporary playwrights further enriched his work, blending inherited traditions with innovative storytelling.

During the late 16th and early 17th centuries, English was evolving into a more complex and flexible literary medium. Unlike Latin, which had long been the dominant language for serious writing, English was still establishing itself as suitable for poetry and drama (Crystal, 2004). Shakespeare, alongside his contemporaries, demonstrated its richness, coining over 1,700 words and phrases that remain in use today, such as “break the ice” (The Taming of the Shrew, 5.1) and “wild-goose chase” (Romeo and Juliet, 2.4). His inventive use of metaphor, wordplay, and blank verse transformed English drama and influenced generations of writers.

Shakespeare’s works reveal deep engagement with classical literature, particularly Roman texts. He drew extensively from Ovid’s Metamorphoses for his mythological references, seen in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and from Plutarch’s Parallel Lives for his Roman plays, such as Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra (Bate, 1993). In addition, fellow Elizabethan playwrights like Christopher Marlowe influenced his early tragedies, evident in the rhetorical grandeur of Richard III and Titus Andronicus (Hopkins, 2008). By blending classical themes with the dynamic, evolving English language, Shakespeare solidified his status as one of the most innovative writers of his time.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s plays were profoundly shaped by the world in which he lived. The political climate of Elizabethan and Jacobean England, the social and economic realities of London, religious tensions, global exploration, and the evolution of the English language all influenced his writing. He absorbed the complexities of his time and transformed them into compelling drama, using history, mythology, and contemporary events to craft narratives that continue to resonate with audiences today.

His genius lay in his ability to take issues specific to his era, such as power struggles, class divides, and cultural anxieties, and elevate them into universal themes. Plays like Macbeth, Othello, and The Tempest explore ambition, prejudice, and colonialism in ways that remain strikingly relevant in modern society. His deep understanding of human nature, coupled with his linguistic creativity, ensured that his works transcended their historical moment.

Works Cited

- Ackroyd, P. (2006) Shakespeare: The Biography. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Armitage, D. (2000) The Ideological Origins of the British Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bartels, E.C. (2008) Speaking of the Moor: From Alcazar to Othello. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bate, J. (1993) Shakespeare and Ovid. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bellingham, D. (2018) Plague and the Playhouse: Shakespeare’s Theatre in a Time of Epidemic. London: Bloomsbury.

- Crystal, D. (2004) The Stories of English. London: Penguin.

- Dollimore, J. (1984) Radical Tragedy: Religion, Ideology and Power in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. Brighton: Harvester Press.

- Dutton, R. (1991) Mastering the Revels: The Regulation and Censorship of English Renaissance Drama. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dutton, R. (2016) Shakespeare, Politics, and Religion. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Greenblatt, S. (2004) Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Gurr, A. (1996) The Shakespearean Stage, 1574–1642. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guy, J. (2016) Elizabeth: The Forgotten Years. London: Viking.

- Haigh, C. (1993) English Reformations: Religion, Politics, and Society under the Tudors. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hopkins, L. (2008) Christopher Marlowe: A Literary Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Porter, S. (2000) London: A Social History. London: Hambledon and London.

- Purkiss, D. (2007) The Witch in History: Early Modern and Twentieth-Century Representations. London: Routledge.

- Shakespeare, W. (2008). The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. UK: Wordsworth Editions

- Vaughan, A.T. and Vaughan, V.M. (1991) Shakespeare’s Caliban: A Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 300K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.