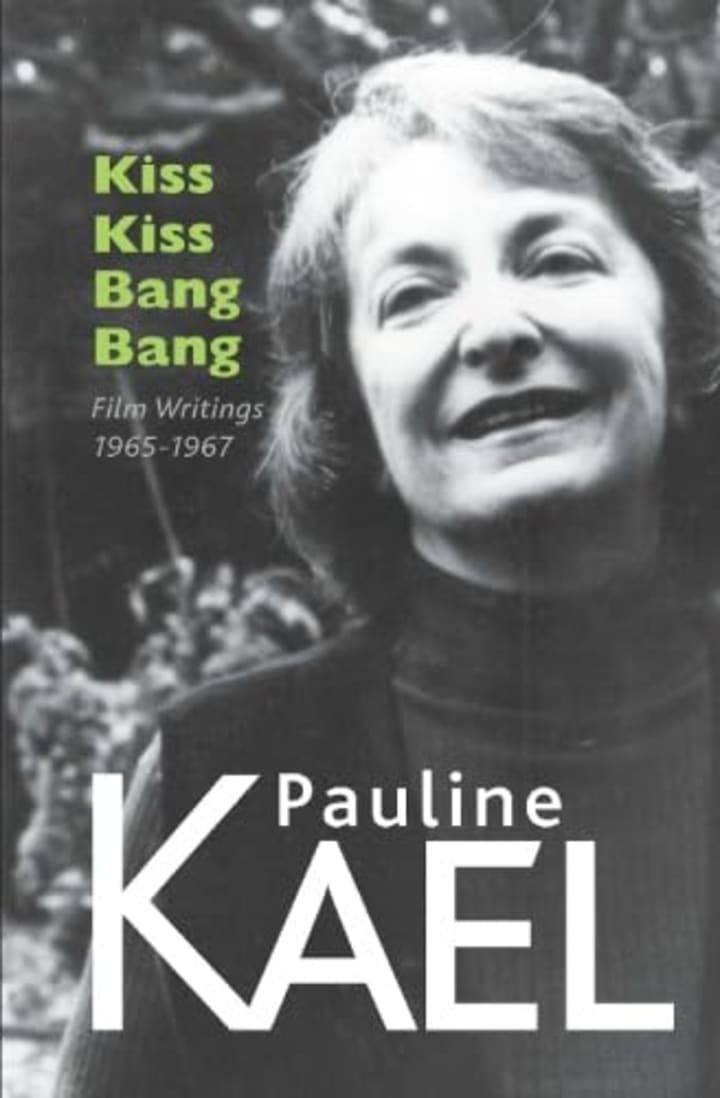

Pauline Kael

"Good movies make you care, make you believe in possibilities again."

Sometimes I pretend to be a 1940s screenwriter. My imaginary ego goes on a trip to tell people about the magic of cinema and the hard work that produces a movie. How you need a writer’s room, money, star power and a way to hoodwink studio executives, because all they care about is money and I’m trying to make art. In 1940s Hollywood, I’m trying to establish cinema as an American artform, with carefully crafted plots, new characters, and risk-taking directors.

I feel good about my work, until some jumped-up critic comes along to tear it all down. I age into the 1950s and 60s when cinema has to compete with rock and roll and TV, and I'm left wondering if we Hollywood types missed our chance to say something real, entertaining and poignant with our technology. The critics are just getting cleverer. Film Studies emerges in the universities. French words get co-opted and academia mangles the joy on screen into something aloof and elitist. All I wanted was to tell a new story, find something that touched people’s hearts, with images that lingered in dreams.

If there was one critic who got that, it was Pauline Kael.

Pauline Kael was born in 1919 to Polish immigrants in California and rose to becoming the most influential film critic of her generation. I could give you the whole back story from the chicken farm to the move East, the unconventional relationships, the forging of a career that could feed her and her daughter and the fandom with an almost cult-like following she had during her tenure at the New Yorker. Sure that’s the film story. And my imaginary screenwriter persona finds it hard to ignore. A proper rag to riches tale, centring a woman with influence.

However, that’s too easy. Here in the 21st century, trying to write about film, her influence is more than that story.

She once said:

"I worked to loosen my style—to get away from the term-paper pomposity that we learn at college. I wanted the sentences to breathe, to have the sound of a human voice.”

There have been two times in life, when I have needed to retrain my writing. The first was after being a manager and policy officer in a local authority. My writing was full of jargon and buzz words. It was applauded because it could fit a template or win grants. It was not good writing.

The second was after completing my PhD. My PhD taught me how to learn at a higher level, how to think, to analyse, to develop argument. It also taught me to doubt. Doubt has its place in thinking. One of the problems we have in the world today is the number of people who do not take the time to doubt their own conclusions. But doubt can make for terrible writing. Every sentence becomes convoluted with caveats. In an attempt to avoid accusations of generalisations, all opinions start with an apology. Facts cannot be simply stated.

Like Pauline I have had to find my voice to produce a different kind of writing.

I get the problems academics have with Pauline Kael.

They don’t doubt her intelligence. In fact, it confounds them. They want it to be used in a particular way – to produce a method of analysis, a systematic approach to viewing and writing about a film. Instead, she is utterly scathing of the big theoretic approach of her day – auteur theory. Auteur theory posits that a film's central creative impetus comes from the director, that directors are the voice behind a movie. Pauline Kael, however, argues that film is great precisely because it is collaborative and that to attribute authorship ignores the beauty of the process.

Instead Kael writes about her experiences of the film. She famously wrote this review of Shoeshine (1946)

I saw the film after one of those terrible lovers' quarrels that leave one in a state of incomprehensible despair. I came out of the theatre, tears streaming, and overheard the petulant voice of a college girl complaining to her boyfriend, "Well I don't see what was so special about that movie." I walked up the street, crying blindly, no longer certain whether my tears were for the tragedy on the screen, the hopelessness I felt for myself, or the alienation I felt from those who could not experience the radiance of Shoeshine. For if people cannot feel Shoeshine, what can they feel?

She writes with wit:

Top Gun (1986) is a recruiting poster that isn't concerned with recruiting but with being a poster.

I get more from her excellent sentences than I do from the mangled, caveated statements of academia. I get something human. As we move away from the human in writing, I get something irreplaceable.

Kael had a sort of untheorized manifesto about cinema, that was asking it to be art, but not obnoxiously pretentious.

As Nathan Heller wrote:

She cared about audiences’ raw responses—amazement, laughter, recognition—because those responses indicated whether a movie could speak for itself in the long run.

So, here is my movie manifesto. I will bring my intelligence and wit to the cinema too. I will write about what resonates, what lingers and the sidelined stories that haven’t made the mainstream, backed by big money. Because as Pauline said:

"In the arts, the critic is the only independent source of information. The rest is advertising."

And I’ll do it my way. Theory will stray into the pages, because I’ve been trained to see and discuss context and my feminism is central to who I am. But I’ll try to keep it accessible. And if something doesn’t make me smile or feel something, I’ll warn others of its lack of heart.

My 1940s imaginary screenwriter pours a slug of whisky and toasts Pauline – thank you for keeping the dream alive that a woman can have power and influence in movie land.

If you've enjoyed what you have read, consider subscribing to my writing on Vocal. If you'd like to support my writing, you can do so by leaving a one-time tip or a regular pledge. Thank you.

About the Creator

Rachel Robbins

Writer-Performer based in the North of England. A joyous, flawed mess.

Please read my stories and enjoy. And if you can, please leave a tip. Money raised will be used towards funding a one-woman story-telling, comedy show.

Comments (11)

Nicely written. Congrats on the TS!!

That line about _Top Gun_ was lethal! This is a fascinating comparative analysis of the evolution of Kael's writing and your own.

This was a love letter to cinema and to voice — bold, witty, and deeply felt. Thank you for channeling Kael’s spirit while making space for your own. I’ll be toasting her too. 🎬

This was such a compelling tribute, not just to Pauline Kael but to the ongoing effort to preserve voice and authenticity in film writing. I really appreciated how you tied your personal journey to hers, especially the challenge of unlearning institutional writing habits. It felt honest, insightful, and inspiring. Your manifesto has heart, and I’d love to read more of your perspective.

Wonderfully written and I loved how you introduced yourself as the imaginary screenwriter of the 40s. Very educational as well, Congrats, Rachel!

What a stunning tribute, and a powerful personal manifesto. Huge congrats on your Top Story!

Thank you for introducing me to Ms. Kael! Such heartfelt, charming writing Rachel! I thoroughly enjoyed this piece! ☺️

Great read! I like how you spoke from the viewpoint of an imaginary 1940s screenwriter. That’s a great angle which gives some imaginary credence to what you’re writing here. Pauline Karl sounds interesting. I will have to read up on her. I would love it if you did a series of reviews on 1940s films.

Very good! I didn't always agree with he, but her writing was/is utterly engaging - very much like your own written voice!

Now this is an article I am going to share far and wide! I began reading her as an undergrad, and even though I have problems with her style and certain weaknesses (she's often readable without being rereadable, and she began to overpraise at the end of her career), I keep her voice in my head. And have you seen the documentary on her life?

Great story that blends art, history, personal anecdote and wit. You have a great voice and it is always a pleasure to read your writing