Ob-Scene and In-Scene: Sex and Blood on Screen

Playing with fire on film, and the decline of reality

Taboo: from the Tongan tabu — set apart, forbidden.”

Fire, Flesh, and the Forbidden

In Bone Tomahawk (2015), S. Craig Zahler opens with a brutal desert murder: two drifters silently slit throats and rob sleeping travellers. In the same year, Gaspar Noé’s Love begins with something entirely different but equally taboo: a scene of mutual masturbation. The protagonist’s face is unflattering, contorted, and real. Actually real! The sex in the film was unsimulated.

“I want to make a film that’s like a flame, like a storm, full of blood, sperm, and tears.”

— Murphy, *Love* (2015)

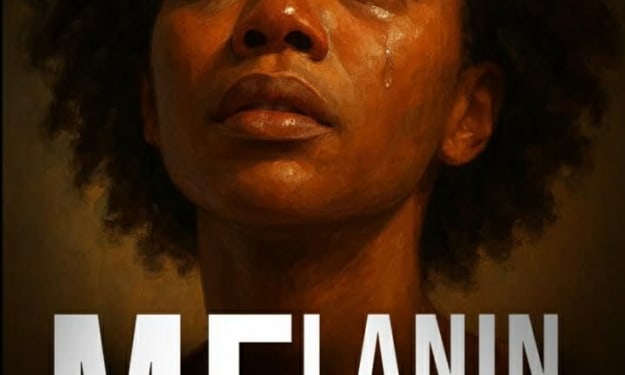

Taboo subjects — especially those rooted in realism, like blood, death, and sex — have long been rare in mainstream cinema. Less so today, perhaps, but since the dawn of the moving image (and long before, in literature), unapologetically human material has stirred controversy.

Some say certain things should not be seen. They do not belong in polite conversation. They should remain hidden, private, and unspoken, so we can continue to deny the pull of eros and thanatos: sex and death.

Many people avoid certain films or books entirely. I, for one, avoid A Little Life because I know I simply couldn’t handle it. Others abandon novels halfway through or struggle for months to finish them. Whether it’s trauma, avoidance, escapism, or denial, there are things we simply do not want to confront.

At the same time, subjects like consensual sex and sexual exploration are often belittled or feared in the public imagination, even though many of us desire and fantasise about them more than we admit.

A Bloody Mess

Some works are considered almost impossible to adapt because of their violence. Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is often described as “unfilmable.”

Several filmmakers have tried. Tommy Lee Jones once secured the rights and even collaborated with McCarthy, but studios baulked at the brutality. Ridley Scott showed interest but never moved forward. Todd Field and Scott Rudin also failed. James Franco filmed test footage in 2016. Now, John Hillcoat — who directed The Road — may attempt another adaptation.

Set in the lawless borderlands of 1849, Blood Meridian follows a teenage runaway known only as “the kid,” who joins a gang of scalp hunters slaughtering Native Americans and civilians alike. At the centre stands Judge Holden, a pale, hairless giant with a brilliant mind and a taste for domination; a character based on a real historical figure.

His violence is what makes the book so unforgettable, and perhaps so difficult to film.

Bone Tomahawk may lack McCarthy’s philosophical depth, but some of its scenes are equally confronting. In one moment, a captive is scalped alive, mutilated, and killed in a ritualistic display of brutality. It is hard to watch, but it functions as a kind of memento mori; a reminder that we are, at the end of the day, mortal animals.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain (1973) suggests that, while we are animalistic, we may also be capable of something more transcendent. The film mixes violence, sexuality, spirituality, and surrealism, using shocking imagery to push viewers toward existential reflection.

Yet for many viewers, such images become barriers rather than gateways.

Cinema has always offered escapism. Even the most realistic films contain elements of fantasy. Real people don’t speak in perfectly structured dialogue. And certain realities, if shown directly, would cross into ethical territory that even documentaries hesitate to approach.

Still, modern cinema often avoids realism altogether. Medical dramas become love stories. Historical films soften their atrocities. We reshape the past into something more comfortable.

Some blood and sex are gratuitous. But sometimes, refusing to show them is equally dishonest.

Even Saltburn (2023) caused public debate not because it was especially violent or graphic, but because it dealt with taboo intimacy and humiliation. Its most discussed scenes were less about explicitness than about psychological discomfort.

Which raises a question: what is happening to sex in cinema?

Too Much or Too Little Skin

Sex scenes have long been controversial. Exploitation — especially of women — has troubled both viewers and performers. And understandably so.

Some actors have spoken out against unnecessary sex scenes. Others describe discomfort or even predatory conditions during filming. These concerns are real and important.

At the same time, sex scenes are disappearing from mainstream films. Television still carries some of that territory, but the mid-budget adult drama — once a staple of cinema — is fading.

It’s a strange paradox: audiences often tolerate extreme violence more easily than consensual sex on screen.

Sex is natural. It is the reason we exist. And many great films rely on it to tell their stories.

Happy Together (1997) opens with a desperate, intimate encounter that colours the emotional tone of the entire film. In Lust, Caution (2007), the sex scenes are essential, revealing shifting power dynamics and emotional complexity under wartime occupation.

Abuse, desire, and violence exist in real life. Art must reflect them, but without perpetuating harm. This is the core dilemma of realism.

There is a fine line between representing trauma and retraumatising audiences. When it comes to consensual sex, many viewers still want these scenes — but they want them handled better, more ethically, and with greater emotional truth.

Not every director succeeds. Some do not even try. But removing sex scenes entirely is not the solution.

Films like Love, with unsimulated sex, blur the line between performance and reality. For some viewers, they are deeply confronting. For others, they are simply better-lit pornography.

But they are not automatically pornographic. Sometimes the sex is awkward, sad, or mundane, and that very ordinariness can make it more human.

Honour and Exploitation

The philosopher Georges Bataille once wrote that taboo and transgression depend on each other. The transgression does not deny the taboo; it completes it.

Films like Precious (2009) show how confronting material can be handled with care. It is a painful film, but an important one. It honours the suffering it portrays rather than exploiting it. This is the function of tragedy: catharsis.

Without art, how do we process pain? Usually, poorly.

Tragedy has always dealt with the unspeakable. Giving horror a shape makes it easier to confront.

Other films push boundaries in more morally ambiguous ways. Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac is difficult not because of its explicitness, but because of the ethical discomfort it creates. Some scenes are deeply troubling, yet they linger in memory because of their emotional complexity.

Not every film handles these boundaries carefully. Some exist purely to provoke outrage. Even if we never watch them, they still shape our understanding of taboo and representation.

They force us to ask: what kind of storytelling are we willing to accept?

The Reality We Can’t Erase

It is probably a good thing that cinema is not flooded with blood and sex. Life is also made of quieter dramas: relationships, work, ambition, pets, and small daily rituals.

But sex and violence are real. They are part of human history and human nature. Wars, betrayals, and desire shape the world we live in. Erasing them from cinema would erase too many necessary stories.

Sex scenes, in particular, have helped open conversations about consent, sexual orientation, ageing, disability, and diverse experiences. Without them, we might be left learning everything from pornography alone.

Of course, there is room for critique. Female pleasure is still rarely shown with honesty. Too often, it is flattened into spectacle and filtered through the male gaze.

But feminist thinkers like Audre Lorde describe the erotic as a source of deep power: a way of knowing and feeling, not just a sexual act. Through that lens, films like Lust, Caution become spaces of emotional truth.

Bataille argued that sex, death, and the sacred are intertwined through acts of excess and transgression. These are the taboos that define us and the ones art must sometimes confront.

In the 1970s, films like The Holy Mountain or Je, Tu, Il, Elle caused outrage. Today, their scandals seem almost quaint. Sometimes the most shocking moment is not the sex or the blood, but something absurdly ordinary.

Blood, semen, spit, and sex are part of our primordial reality. They can be mishandled, exploited, or used cheaply. But eliminating them entirely would not be realism. It would be censorship disguised as comfort.

About the Creator

Avocado Nunzella BSc (Psych) -- M.A.P

Asterion, Jess, Avo, and all the other ghosts.

Comments (1)

Some very valid points raised here. Thank you for getting this discussion underway!