"Nothing Can Perish...Things Merely Change Their Appearance."

Classical Mythology's Influence Upon 19th Century Literature

Background and Context:

I love writing about the 19th Century and as I've said with my essay on 'Jane Eyre' I was thinking about starting a podcast about it all so I have lots of material. I thought and thought about it and I don't think anyone wants to listen to my posh British accent talk about literature so now, I just have tons of essays and nothing to do with them. So, I've decided to release them on here. At least I know some of you will appreciate them. If you look through my posts and my profile, you can see that these are coming out intermittently. I have to say though, this one perhaps contains some of my favourite ideas and literature. Enjoy.

"Nothing Can Perish...Things Merely Change Their Appearance."

Classical Mythology's Influence Upon 19th Century Literature

The 19th century, defined by the intellectual demand of the Romantic and Victorian periods, witnessed a cultural re-engagement with the classical world called 'neoclassicism'. Greek and Roman mythology, long embedded in Western literary tradition, found renewed resonance in the imaginations of writers of this new era. Against the backdrop of scientific advancement, industrialisation, and shifting moral codes, myth offered a symbolic language through which authors could explore deep anxieties surrounding identity, ambition, beauty, and the limits of human power. This is something grand and beautiful, but also fraught with terror.

I will examine how classical myths were reimagined in key nineteenth-century literary works, offering modern interpretations of ancient archetypes. In Frankenstein (1818), Mary Shelley invokes the myth of Prometheus to depict Victor Frankenstein as a tragic overreacher; a man who, like the Titan, steals divine power to create life. Shelley’s subtitle, The Modern Prometheus, makes this link explicit. Victor confesses:

“Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through.”

(Shelley, 1996, p. 33)

A statement reflecting the desire to transcend natural limits, and the inevitable punishment that follows.

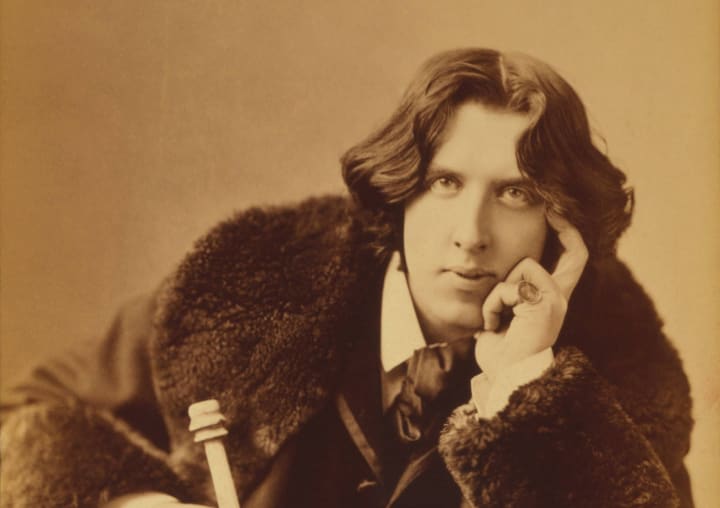

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) similarly reworks classical myth, most notably that of Narcissus. Dorian, enraptured by his own portrait, becomes a modern echo of the youth who “fell in love with his own reflection” (Ovid, Metamorphoses). Wilde’s character is consumed by vanity and aestheticism, eventually facing the ruin his self-worship invites:

“Each man sees his own sin in Dorian Gray. What Dorian Gray’s sins are no one knows. He who finds them has brought them”

(Wilde, 2003, p. 145).

The mythic undercurrent renders Dorian less an individual than an archetype: an embodiment of the dangers of unchecked self-obsession.

I will also consider Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), where the Oedipal themes of fate and tragic innocence surface, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Birth-Mark (1843), which revisits the Pygmalion myth through a Gothic, moral lens. In each case, ancient mythology is not simply revived but reinterpreted to meet the concerns of the 19th century mind. These texts demonstrate how myths endure, not only as aesthetic tools but as cultural mirrors reflecting humanity’s evolving fears and fascinations.

Prometheus/Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) is subtitled The Modern Prometheus, a clear signal of the novel’s mythological foundation. In classical mythology, Prometheus is the Titan who defies the gods by stealing fire and giving it to humanity, an act that enables human progress but also incurs divine wrath. His punishment of being chained to a rock where an eagle consumes his liver daily, becomes a symbol of eternal suffering for transgression. Shelley reinterprets this figure in the form of Victor Frankenstein, a scientist whose desire to create life mirrors Prometheus’ bold challenge to divine authority.

Victor’s act of creation is framed not as benevolent but coated in hubris. He seeks glory and power rather than enlightenment or moral good. He confesses:

“Learn from me… how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world”

(Shelley, 1996, p. 38).

The warning encapsulates one of the novel’s central themes: the perils of overreaching ambition. Like Prometheus, Victor crosses natural boundaries in his pursuit of forbidden knowledge, and like Prometheus, he pays the price. His creation becomes a curse rather than a triumph, leading to the destruction of all he loves.

Critics have long highlighted the Enlightenment anxieties embedded in Frankenstein. As George Levine argues:

“Victor’s scientific ambition represents not only the power of Enlightenment rationality, but also its terrifying consequences when untempered by moral responsibility”

(Levine, 1981).

In this way, Shelley places Victor at the intersection of Enlightenment and Romanticism: simultaneously fascinated by scientific potential and appalled by its ethical void. The Promethean archetype is reimagined to reflect contemporary fears about the rapid advancement of science and its implications for humanity.

Also, Prometheus in Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound is a figure of heroic rebellion, one who suffers for his compassion toward humankind. Victor, by contrast, is a far more ambiguous figure. His suffering arises not from noble sacrifice but from selfishness and abandonment of responsibility. As Anne Mellor notes:

“Shelley condemns Victor not for his scientific curiosity, but for his failure to assume the responsibilities of a creator”

(Mellor, 1988, p. 120).

In Frankenstein, the myth of Prometheus is not merely echoed, it is transformed. Shelley uses the myth to interrogate the ethics of creation, knowledge, and human ambition. The result is a modern myth of its own, in which the tragic creator is not a god-defier punished by fate, but a man undone by his own flawed humanity. Shelley's extended metaphor in this comparison seeks to teach us about the terrors of quick progression - something we are seeing more and more of today in our own world.

Narcissus/The Picture of Dorian Gray

In The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), Oscar Wilde draws on the myth of Narcissus to craft a cautionary tale about beauty, identity, and moral decay. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Narcissus is a beautiful youth who falls in love with his own reflection, unable to tear himself away until he withers into a flower. Wilde reimagines this myth through Dorian Gray, a young man who becomes infatuated with his painted likeness: an image that captures his youth and perfection while his real self degenerates under the weight of sin and indulgence.

Dorian’s initial enchantment with the portrait mirrors Narcissus’s tragic self-love:

“When he saw it he drew back, and his cheeks flushed for a moment with pleasure. A look of joy came into his eyes, as if he had recognised himself for the first time”

(Wilde, 2003, p. 27).

This recognition marks the beginning of Dorian’s descent, as he comes to value surface appearance above all else. The myth of Narcissus thus functions not merely as allegory but as a psychological underpinning of Dorian’s disintegration, his obsession with eternal beauty becomes a fatal flaw.

The influence of aestheticism and hedonism is crucial to Wilde’s reworking of the myth. Lord Henry, the novel’s mouthpiece for aesthetic philosophy, urges Dorian to “realise your youth while you have it… Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you!” (Wilde, 2003, p. 29). In doing so, he encourages a worldview where beauty and sensation are pursued at the expense of morality. Dorian becomes the embodiment of this ideology taken to its extreme: an eternal Narcissus who sacrifices his soul for the illusion of unchanging physical perfection.

Wilde critiques not only personal vanity but a broader cultural fixation on surfaces. As Linda Dowling argues, “Wilde explores the dangers of aestheticism when severed from ethics” (Dowling, 1994, p. 106). The novel suggests that the pursuit of beauty without conscience leads to a hollowing of the self. Dorian’s final act of destroying the portrait symbolises his recognition of the internal corruption he can no longer deny. The result is his own death, a grim fulfilment of the Narcissus myth’s moral: obsession with the self leads ultimately to annihilation.

Again, we can link this to our modern day by the very sight of those who unethically produce and enhance rigorous standards of beauty on to others with the implied message of appearances being the only thing that really matters. There applications include but are not limited to dating apps and of course, Instagram.

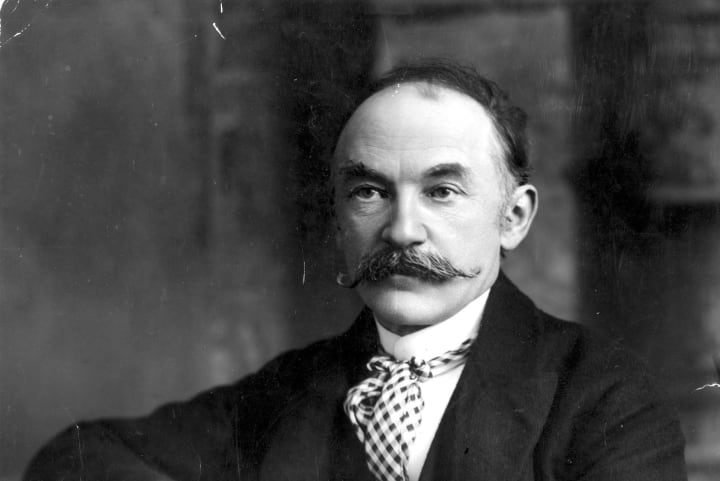

Oedipus/Tess of the d'Urbervilles

In Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), Thomas Hardy crafts a tragic heroine whose life is shaped by forces beyond her control, echoing the fatalism of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. Like Oedipus, Tess is entangled in a web of circumstance, ancestry, and prophecy that leads inexorably to her downfall. From the moment Tess learns of her aristocratic lineage, a chain of events is set in motion that mirrors the tragic inevitability at the heart of Greek drama.

Hardy makes his fatalistic intentions clear early in the novel: “It was to be. There lay the pity of it” (Hardy, 2008, p. 85). This simple declaration foreshadows Tess’s powerlessness in the face of destiny. Critics have often noted Hardy’s use of “Greek-style tragedy in modern pastoral settings” (Morgan, 2006, p. 113), and nowhere is this more evident than in Tess’s trajectory, which combines beauty, innocence, and a haunting sense of doom. Like Oedipus, Tess is punished not for wickedness but for actions shaped by ignorance and inherited burden.

Themes of guilt and purity are central to both Tess and the Oedipus myth. Tess, a victim of Alec d’Urberville’s manipulation, is treated by society and even by Angel Clare as if morally impure. Her confession:

“I am not the only woman in the world who has suffered as I have suffered,”

(Hardy, 2008, p. 210)

highlights the injustice of moral judgment in a world governed by chance and social hypocrisy. Her suffering reflects what Peter Widdowson calls Hardy’s critique of “the rigid Victorian dichotomy of virtue and vice” (Widdowson, 1989, p. 74).

Moreover, Hardy explores the tension between determinism and morality: a central concern of Victorian thought. Tess’s fate is presented as inevitable, yet she is judged as if she had choice. This contradiction mirrors Oedipus’s plight: forewarned and doomed, yet still held responsible. As Angel cruelly concludes, “The woman I have been loving is not you” (Hardy, 2008, p. 214), Tess is condemned both by fate and by human hypocrisy.

By reworking Oedipal themes within a Victorian framework, Hardy uses myth to explore the limits of personal agency, the cruelty of social mores, and the tragedy of moral absolutism in a world ruled by indifferent forces.

Another way in which we can see this through our own modern lens is that there is a clear progressiveness followed by a moral deterioration. It has no become socially acceptable (and sometimes even commendable by some sociopathic standards) to be unkind, uncouth and anti-social towards others. We cannot help but look back to see we have already been warned about it. We have ignored that warning. Moral absolutism has turned into social-media mob rule. It is ineffective.

Orpheus/Manfred

Lord Byron’s Manfred (1817) presents a deeply Romantic reimagining of the Orpheus myth, using classical allusion to explore the anguish of a tormented soul. Like Orpheus, who descends into the underworld to retrieve his lost Eurydice, Manfred is consumed by grief and guilt over a mysterious, forbidden love. His existential yearning and defiance of divine powers position him as a tragic artist-figure, embodying the Romantic ideal of the suffering, solitary genius.

Byron’s protagonist evokes the Orphic tradition not only through his attempts to commune with spirits but also in his rejection of religious consolation. Manfred cries out, “The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life” (Byron, 1991, I.i.10), signalling his refusal of redemptive faith and a tragic awareness that knowledge brings only isolation. His pursuit of forbidden insight is both Promethean and Orphic; a descent into metaphysical darkness rather than heroic triumph.

The play is saturated with mythic and classical motifs, blending the Gothic sublime with ancient echoes. As Angela Esterhammer notes, “Manfred rewrites myth to present art as both a refuge and a curse” (Esterhammer, 2005, p. 92). Manfred’s incantations, visions, and invocations of elemental spirits place him in a liminal space between worlds, much like Orpheus’ underworld journey. Yet unlike Orpheus, Manfred refuses to plead for salvation or forgiveness. When offered absolution by the Abbot, he firmly rejects it: “Old man! ’tis not so difficult to die” (Byron, 1991, III.iv.151).

Byron’s use of Orphic themes also resonates with Romantic notions of cosmic alienation. The grandeur of the Alps, the silence of the spirits, and Manfred’s isolation reinforce the idea that the universe is indifferent to human suffering. As Jerome McGann argues, Byron’s Manfred “turns classical myth into a meditation on existential despair” (McGann, 1980, p. 115). In this sense, Orpheus becomes not only a figure of artistic power but also of tragic futility.

Through Manfred, Byron fuses classical and Gothic elements to express the anguish of the Romantic artist. The Orphic descent is no longer a hopeful quest but a doomed confrontation with the abyss, where the price of knowledge is alienation, and the only redemption lies in artistic self-expression.

Of course, we are intended to think AI will turn our world into just this. People who know things deeply will be alienated as having shunned the new dystopian world of knowing nothing, being submissive, and getting a machine to answer all the questions on life and all in between. Only a select few will be able to express themselves with articulation and even though this will present us with redemption it will definitely create a class system of intellect even within those of us who have degrees. We will have to accept it. Knowledge will bring isolation.

Conclusion

All in all, these reworkings reveal the adaptability of myth to new cultural paradigms. As Richard Buxton suggests:

“...myth does not lose its power in translation across time; it becomes newly meaningful”

(Buxton, 2004, p. 7).

By reshaping ancient narratives to reflect contemporary struggles, 19th-century authors laid the groundwork for the mythic retellings that would flourish in the 20th and 21st centuries. From modernist allusions in T. S. Eliot to contemporary feminist reimaginings, these classical echoes continue to resonate and get reflected into different eras of literature.

Works Cited

- Buxton, R. (2004). The Complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Byron, G.G. (1991). Manfred. In: J. McGann, ed. Lord Byron: The Major Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 360–392.

- Esterhammer, A. (2005). Romanticism and Improvisation, 1750–1850. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dowling, L. (1994). Language and Decadence in the Victorian Fin de Siècle. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hardy, T. (2008). Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hawthorne, N. (2006). The Birth-Mark. In: The Birth-Mark and Other Stories. London: Penguin, pp. 1–18.

- Levine, G. (1981). Frankenstein and the Tradition of Realism. In: G. Levine and U.C. Knoepflmacher, eds. The Endurance of Frankenstein: Essays on Mary Shelley's Novel. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 3–31.

- McGann, J. (1980). Byron and Romanticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mellor, A. (1988). Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. New York: Routledge.

- Morgan, R. (2006). The Tragic Vision in Thomas Hardy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ovid. (2004). Metamorphoses. Translated by D. Raeburn. London: Penguin Classics.

- Shelley, M. (1996). Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sophocles, (2004). Oedipus Rex. Translated by R. Fagles. London: Penguin Classics.

- Wilde, O. (2003). The Picture of Dorian Gray. London: Penguin Classics.

- Widdowson, P. (1989). Hardy in History: A Study in Literary Sociology. London: Routledge.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 300K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (3)

Nice art bro.

Excellent work and I can tell your passion is aligned with your passion to detail and research for your subjects

Very nice