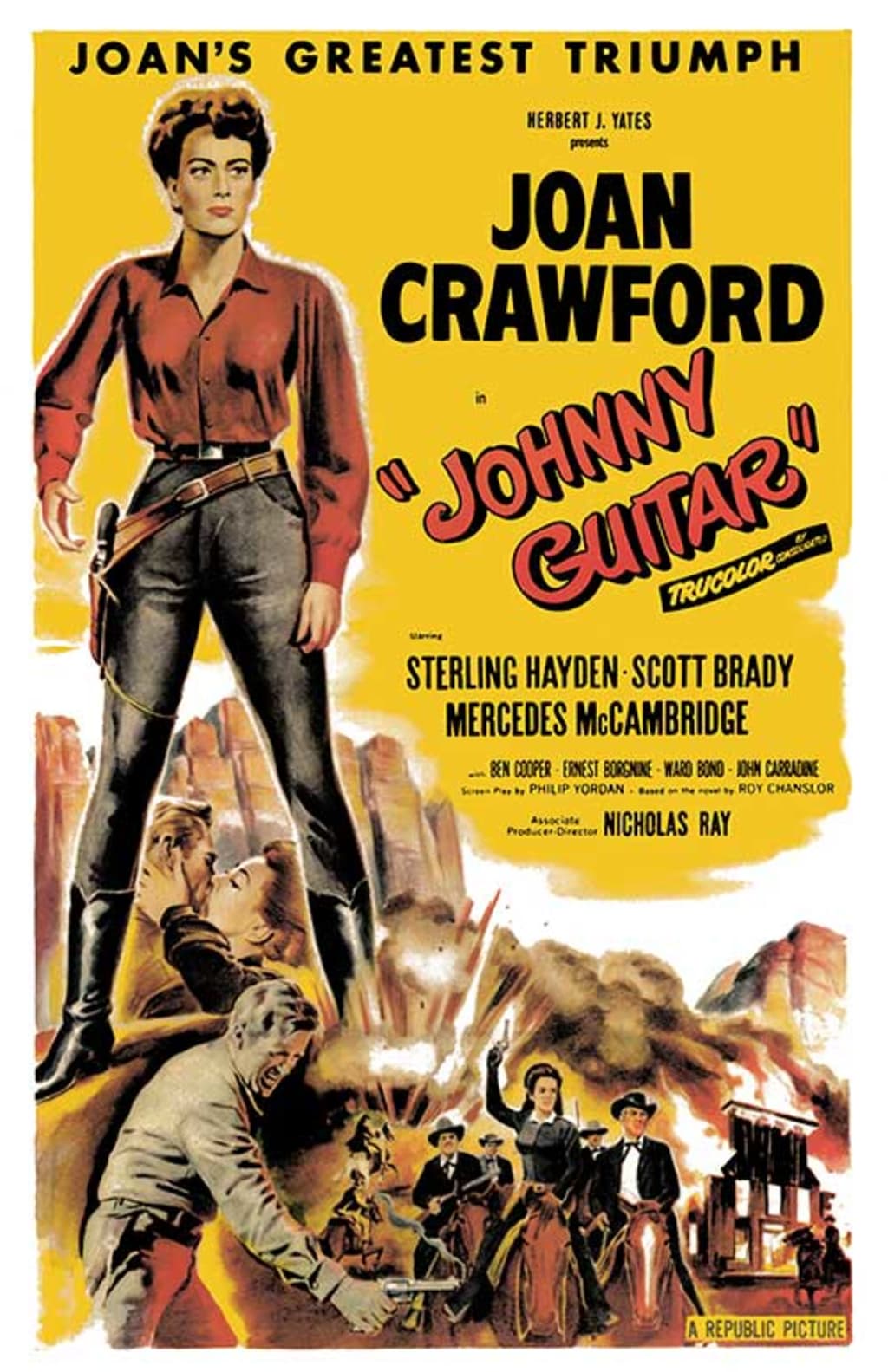

Johnny Guitar (1954)

A Weird and Wonderful Cinematic Experience

At the weekend, I went to see Johnny Guitar (1954) at the local art house cinema, as part of their season of Women and Westerns. I don’t usually watch Westerns so I only have a passing knowledge of the tropes and conventions of the genre. When they appeared on the TV in my parent’s sitting room, westerns rarely grabbed my attention. I came up with a theory that I don’t like “sandy” films; the colour palette bored me. Same as I’m not good with the over-use of metallic hues in sci-fi.

But this was a chance to see Joan Crawford on the big screen. Also I had a notion that I might write about the other woman in the film, Mercedes McCambridge and her curious career. That might still happen. But I came away from the film wanting to write about the experience of watching the film in the cinema.

It was a Friday night, so I went with my partner and we called it a “Date Night”, but it was my choice and my desire to see the film that drove the evening. He had very little interest in the movie, but was happy to sit in the dark with me and share a story. Neither of us had seen the film before. I knew a little about it. I knew it had been panned by American critics at time of its release, but I also knew it had been lauded by French New Wave critics for its gender and genre-bending.

And so date night began. We arrived, found our seats, checked in on Facebook, so people knew we existed.

Going to see a 1950s camp classic is a real opportunity to people watch. Who, other than the quirky eccentricity of me, would want to see this film? It had sold quite well. It was curious mix of mums and sons, gay and straight older couples and seated a couple of rows in front of us a single woman, with gorgeous curls. A man approached her to see if she was part of the ‘meet up’? She misheard and said, “Yes, Johnny Guitar.” He continued to talk to her, so she had to check what was happening. He was surprised she had gone to see a film on her own. It could have been a meet-cute from a rom com, but it was just an awkward exchange in which they both remained polite and he was possibly a little too eager to keep talking. She was obviously relieved when the lights went down. And thankfully a man arrived during trailers who was part of the ‘meet-up'.

I found the whole exchange a delight to eavesdrop. My partner was cringing.

Big Western sounds filled the auditorium and Joan Crawford’s name appeared in large letters. The dusty technicolour begins, with explosions of sand, a lonesome cowboy, a stage-coach hold-up and shooting.

Joan makes her debut screen appearance as Vienna shortly after. It is an impressive entrance from the balcony of her saloon, dressed in black trousers and shirt with a green tie. Her stance is masculine and defiant. Shot from below, she looks self-assured, a towering presence, magnificent.

As Sam says, almost directly to camera, when she orders him to light the lamp:

“Never seen a woman that’s more a man. She thinks like one, acts like one, and sometimes makes me feel like I’m not”.

The film is centred on the rivalry of two women – Vienna (Joan Crawford) and Emma (Mercedes McCambridge). Emma is evil. She is not the sultry, sexy evil of film noir. She is simply mean, nasty, callous. She is not a siren luring men to their death. She is a bully desperate to be top dog. She is the leader of the posse.

Vienna is the hunted. But she also has a past:

“A man can lie, steal and even kill. But as long as he hangs on to his pride, he’s still a man. All a woman has to do is slip once and she’s a tramp. It must be a great comfort to you to be a man”.

I could say many clever things about the film. I could emphasise its message about the faceless, baseless nature of trial by crowd:

“A posse isn't people. I've ridden with 'em, and I've ridden against 'em. A posse is an animal that moves like one and thinks like one.”

The film was released in 1954, when Hollywood was embroiled in the McCarthy era politics and mob justice. Ward Bond, the actor who plays McIvers, was one of the main agents responsible for the spreading of hysteria among the actors, whereas Starling Hayden, who plays the title character, resisted being an informer as much as he could, but finally gave in. This was a film that understood the hysteria of the posse and the consequences of witch hunts. And the posse in the film, led by Emma, ferociously, unreasoned, all clad in black is an obvious metaphor for the times, especially when set against the white evening dress of Vienna, a woman just trying to make a living.

I could also talk about the gender performances. Two female leads, with a coded lesbian performance and feminised male characters who dance and sing.

But instead, I’m going to talk about how the movie works now and what it felt like to watch a movie made in 1954, seventy years later. The jolts of connection and disconnection.

The big connection was the real joy in watching two women take up that much space on a screen. Vienna’s character as a flawed and complex heroine – a woman trying to do the right thing, but also needing to survive, is still hard to find on screen. And Emma is a snarling, spiteful woman who doesn’t feel a need to justify her actions. Again unusual to see portrayed on film.

The film is camp and melodramatic. And the heightened performances, the close-ups of wide-eyed extremes, the over-stating of traditional gender roles, at times took me out of the action. It was like parody, but without the knowing wink of satire. So much so, that the horror of a lynching gets lost in the hyperbolic performances.

Close-ups of Joan on the big screen meant I found myself focusing on the mascara, the over-drawn lips and the over-zealous cosmetic dentistry. Mercedes had a more natural look, but it was held in a constant snarl.

Francois Truffaut praised the film as:

“A Western that is dream-like, magical, unreal to a degree, delirious.”

And that can be quite a challenge for a modern audience. To take in the dream, the magic, the unhinged world that is presented. It is an excessive film. It is a film of sensory over-load. It is a film that is hard to take seriously.

I was glad to see it at the cinema, on a big screen, where my phone was put to one side. And it made me want to see more older films in this way, instead of them being reduced to a laptop screen and interrupted by the distractions of modern life.

It was also good to see it with company, so that we could discuss what worked and what didn’t. And I could try out pretensions like, “it’s a western where the cowboys’ enemy isn’t the Indians, but encroaching capitalism.” (I wonder if the people on the ‘meet-up’ got to share such gems.)

Douglas Brode says, in The Films of the Fifties, that:

“the people who love and hate the film agree on one point: Johnny Guitar is the weirdest Western ever made”

I probably won’t go and see many Westerns, but I can say that I got to see the weirdest Western. I got to see cutting edge, avantgarde cinema seventy years after it was made.

And it was a subversive, delicious, delirious experience.

If you've enjoyed what you have read, consider subscribing to my writing on Vocal. If you'd like to support my writing, you can do so by a regular subscription or leaving a one-time tip. Thank you.

About the Creator

Rachel Robbins

Writer-Performer based in the North of England. A joyous, flawed mess.

Please read my stories and enjoy. And if you can, please leave a tip. Money raised will be used towards funding a one-woman story-telling, comedy show.

Comments (3)

well done

A classic! So very Nick Ray. I enjoyed reading your thoughts on it!

I like old movies but never seen this one but I'm definitely going to try to see it.