Why did Portugal build a maritime empire in such a short period?

With a population of a million or so, Portugal is considered poor and weak in Europe

Portugal was the first country in European history to expand abroad. According to the popular narrative, the Portuguese discovered a direct route to Asia around the southern tip of Africa in 1498, and it took them less than 20 years to establish a worldwide maritime empire, which has even been cited as a model for the rise of great powers.

There are obvious difficulties in this statement: around 1500, Europe had not yet emerged from the Middle Ages. Portugal, with a population of a million or so, was poor and weak in Europe, so how could it come to Asia and build a great empire in such a short period?

Portugal's maritime advantage

To obtain pepper, the Portuguese traveled thousands of miles to India, there are good and bad. The joy is that the price of pepper in India is cheap, and there are all kinds of products around: on the spices have ginger, cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg; on luxury goods, more precious stones, ivory, burning incense, sandalwood, and even Chinese silk, porcelain.

But in the face of these coveted products, the Portuguese encountered two problems. The first was that European goods did not have a market in Asia and could not be sold at a good price, so they had to buy Asian goods with precious metals. The Portuguese were unable to intervene in the trade network that had already been formed around the Indian Ocean, watching pepper and spices everywhere, but could not get good goods. In the world of 1500, Europe was an economically backward region and at a disadvantage in trading with Asia.

The Portuguese, however, found themselves at an advantage beyond trade and commerce, as Asian sailing ships were no match for them in naval warfare. In modern times, strong ships and cannons require a foundation of steel, electronics, and weapons systems, spelling technical standards, and industrial manufacturing capabilities, and it is difficult for economically backward countries to compete with technologically advanced powers. But before industrialization used wooden ships with guns mounted on them, relying on the craftsmanship of carpenters and blacksmiths. The ability to fight at sea did not depend on the economic or technical level but was created by the treacherous environment.

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, the trade around the Indian Ocean was generally peaceful, with interactions between various places, and although there were occasional pirates, there were not often wars at sea. The ship-runners, mainly Arab merchants, were individuals, supported by their families and friends, and paid taxes everywhere, without the need for political protection or the effort to arm themselves.

Portugal, on the other hand, came from a Europe where lords were at war, and commerce was more closely related to politics: the establishment of bazaars, the exploitation of mineral deposits, and the opening of trade all required the king's concession and protection. Around the Mediterranean, wars were often fought at sea. Venice and Genoa fought over entrepôt trade, and there was no end to the fighting at sea. Portuguese exploration, which began with raids on the coast of North Africa, was also authorized by the king to trade while being a pirate. Their sailing ships were both commercial and warfare and accumulated a lot of experience in naval warfare. Bumpy sailing from Europe to India, they have seen the wind and waves, the ship is strong, walking in the middle of the ocean skillful. They were financed by the king, their sailing ships were equipped with guns on both sides, and more warriors than merchants wore swords among their crew. Against the Arabs at sea, the Portuguese had a clear advantage in terms of organization, equipment, and experience.

In terms of economic power, India was the most powerful country in the Indian Ocean. It was just that the west coast of the Indian peninsula was politically divided, with caste, religious and geographical conflicts between the vassals, with interlocking roots and constant fighting. Most of the battles were fought on land, with tens of thousands of people, with weapons like swords and spears, and usually not to the point of death, but just to shout, to make a show, to talk while fighting, and to reach an agreement without seeing blood.

As outsiders, the Portuguese could not figure out the details of these conflicts, but it was not difficult to find the gaps between them. Their guns were placed on warships, more conveniently maneuverable than those on land, and could be equipped with larger caliber heavy guns. Several warships clustered together to form a network of firepower and enjoyed considerable advantages against the few small guns that the Indian vassals placed between scattered pieces along the coast.

Da Gama first arrived in India in 1498 and went back four years later, when his fleet began to plunder the seas. In the next decade or so, the Portuguese seized several strongholds on the west coast of the Indian peninsula, further south to Malacca in Malaysia, and north to the island of Hormuz at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. Using these strongholds as bases, they issued passes, forced merchants to buy them, and punished merchant ships that sailed without permits. On the other hand, they forced the Indian coastal lords to sign trade agreements, using the precious metals shipped from Europe plus the revenue from the passes to buy Indian spices cheaply and sell them back in Europe.

The so-called Portuguese maritime empire, to put it bluntly, is a string of coastal tollbooths, forced to buy and sell. At that time, sail-driven, naked-eye view of the technical level, these positions are not enough to control the Indian Ocean merchant ship traffic. But many merchant ships felt that it was better to do more than less, and were willing to pay the Portuguese for a safe journey and a few more places to rest.

Traditionally, the most important passage for spices to the north was the narrow Red Sea, only 2,000 kilometers long, but along the way, there were many reefs and small islands, and the coastal mountains made the wind direction difficult to grasp, and ships were prone to run aground and hit the reef. Therefore, the Red Sea can only run small ships, and also dare not drive at night. Indian goods first by the Indian Ocean by large ships to the Red Sea entrance of the port of Aden, unloaded on a small ship to enter the Red Sea, north to the Gulf of Suez and to unload, and then take more than 100 kilometers of land to reach Cairo. Down, Indian goods to Cairo to more than 20 times the price increase. Venetian merchants were in Cairo to buy spices, along the Nile into the Mediterranean Sea, shipped back to Italy, and then shipped to various parts of Europe.

Outside of Egypt, Italians could also buy Asian goods from around the Black Sea. But in the fifteenth century, the rise of the Ottoman Empire had a serious impact on the trade around the Black Sea, which only left Egypt a channel, monopolized by Venice. Other Italians had to run to Portugal and Spain to seek opportunities, dreaming of finding a direct route to Asia in the ocean.

Half a century later the dream came true, Da Gama completed the first voyage to India, and Venice's monopoly was also broken. Some people even gloated that Venice will be able to fish for a living. The two routes have mutual advantages and disadvantages. The trouble with the old Red Sea route is that it is not direct, unloading and loading several times, but from India through the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, the Nile, and the Mediterranean, to Venice only 8,000 kilometers up and down. The new route of the Cape of Good Hope can run large ships in the ocean, bypassing the control of the Muslims, but it is a long way, from India to Portugal voyage of 20,000 kilometers, and the ocean voyage is very difficult, the wind and waves are difficult to master, the average calculation of the loss of nearly one-third of the sailing ship, the proportion of personnel loss is higher. In this kind of gambling voyage, if there is no price rise dozens of times the huge profits, no one will be willing to run. Therefore the competition between the two routes, the decisive factor is not in the price.

Good luck to the Portuguese

The opening of the Cape of Good Hope shipping lane made Egypt and Venice doubly worried. Compared with Portugal, Venice had a stronger navy and a richer economy. But the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea are separated by land, the Venetian fleet can not enter the Indian Ocean. It could only encourage Egypt to take action and secretly finance Egypt to set up a fleet of ships to attack the Portuguese in India. At that time, the Mamluk dynasty ruling Egypt believed in Islam, and Venice was suspected of religious collaboration with the enemy. But the immediate interests of commerce were at stake, and God's considerations could only be set aside for the time being.

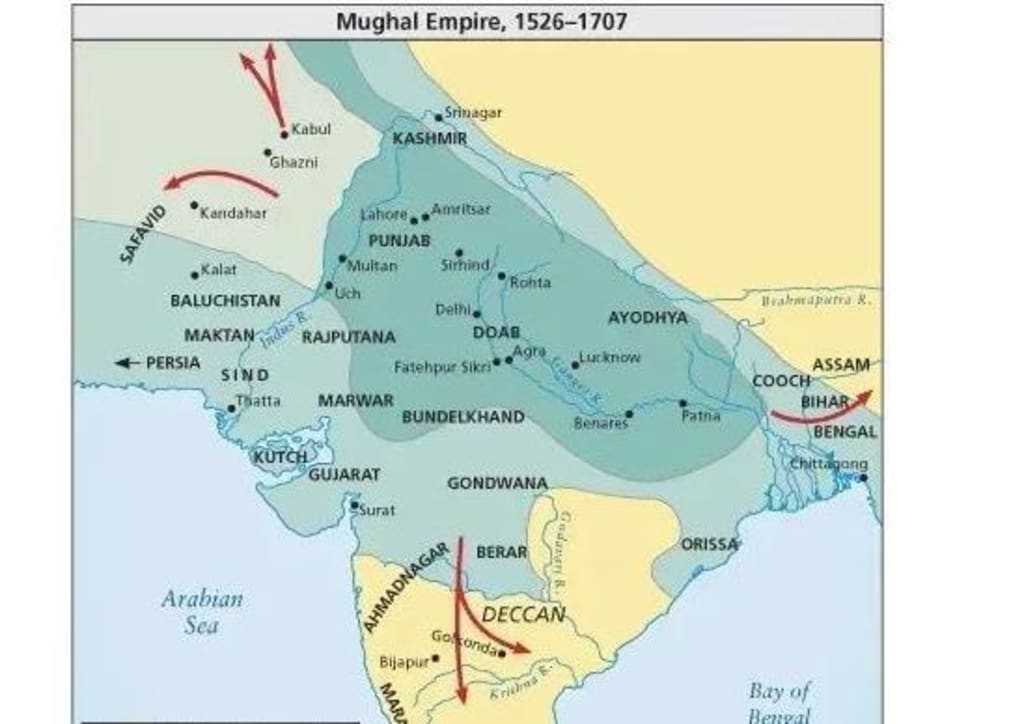

Before the modern era, coastal ports were far less important than river cities, and river trade was far greater than sea trade. In sixteenth-century Asia, whether Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Bombay, or Madras, they were all just small, nameless places. The Mughals controlled the great rivers and the interior of India and had little interest in the coast. In contrast, the Portuguese, who were active on the sea, were also reluctant to enter the inland rivers because there was not enough room for maneuvering in the rivers, and they could not take advantage of being too close to the river banks, and they were even more powerful on the shore. Therefore, the Portuguese were confined to the coast, and the Mughal empire was not a problem.

As a result, the overall influence of the Portuguese on India was limited. Even in the 17th century, all the trade of the Portuguese, British, Dutch, and other European countries in India combined was not even comparable to the volume of business of a famous Indian merchant at that time. The main result of the Portuguese-Indian trade was the flow of precious metals from Europe into India in exchange for the pepper that was so abundant there, contributing to the Mughal coffers and currency circulation in no small measure. By and large, the economic relationship between the two was one of complementarity, not conflict.

Around 1550, Portugal was at the height of its power, with more than 50 overseas strongholds spread over three continents: Asia, Africa, and Latin America, making it a "great empire of the world. But the so-called stronghold, basically a port fortress, plus a few warehouses, the impact on the surrounding inland is very small, only to allow ships to enter the port to dock, rest and reorganize, replenish supplies, loading and unload goods. Most of the strongholds in Asia were located on the west coast of India, where the Portuguese used them as bases for patrolling the coast, collecting money to buy spices,d transporting them back to Europe. The strongholds in Africa were mostly for supplying ships to and from India, and also for purchasing some African specialties. America's stronghold is less, confined to the coast of Brazil, or the surrounding sparsely populated barren areas.

This empire did not have the responsibility of protecting the people and governing the world, but only one important task at hand: to transport spices from Asia back to Europe to sell, in essence, an armed long-distance trafficking syndicate. The governor was appointed by the King of Portugal, and the officers of the forts, the accountants of the warehouses, the captains of the sailing ships, and so on, were all officials under the governor's leadership, receiving public salaries and working for the King.

To us, who are used to the presence of the government, this arrangement is nothing special. But in the sixteenth century in Europe, it is very important. There was no official government in Europe under the feudal system, the world was divided among the nobles, and there was no unified law or judiciary, no centralized finance and taxation, no civil service, and even no unified professional army. The nobles had their castles and private armies and came to the king's defense only when ordered to do so. Portugal, which was poor and weak, set up a political system to govern its overseas empire.

It is not difficult to understand the starting point of the Portuguese king, as the overseas expeditions were not only long, costly, and risky but they could only be completed thanks to the long-term support of the royal family. After the opening of the route, sending ships down to India remained expensive, and the cost of building a ship for a voyage could cost three-quarters of the royal family's annual income, which was spent in blood. The Portuguese king was naturally reluctant to take out the huge profits from the transport of spices back to Europe, but had to be monopolized by the royal family: the spices had to be recorded in the king's name, the expenses and income had to be recorded in detail, private capital could only participate in the dividends under the royal accounts, and even the booty from the sea robberies had to be recorded and rewarded only after the return.

However, the establishment of the state system was not so easy. The people who went to India were adventurers, not civil officials who talked about rules. Coming to a foreign country to fight in blood, was to care about the command or supervision of Lisbon. What's more, the situation overseas, reported to the king at least six months, to get instructions for more than a year, unified dispatch is simply impractical. Moreover, the "Indian government" was aimed at making money, and the capital was indeed invested by the King of Portugal, but the people who went to India were gambling with their lives. Corruption, false accounting, smuggling, etc., were common among overseas officials.

The monopoly of the Portuguese king on spices was maintained for half a century, and around 1550 there were already many problems. In India, the Portuguese imposed the purchase price of spices, which was not allowed to change for a long time. The Indian merchants were forced by fire to comply, but the goods they offered were mostly of inferior quality. A more serious problem was the private business of overseas officials, who bought spices and smuggled them back to Europe or sold them from one part of Asia to another. The costs of maintaining the strongholds, such as pay, gunpowder, fortress construction, ship maintenance, etc., were charged to the official accounts, while the Asian goods bought were charged to the private accounts of the officials. While the Portuguese king spent a lot of money every year to maintain the empire, the benefits of the spice trade flowed into the pockets of overseas officials. In addition, many Portuguese settled in Asia, ran businesses, served as mercenaries, married local women, followed local customs, and renounced Christianity and converted to Islam or Hinduism, becoming overseas Portuguese and finding a more fulfilling life in Asia. Portugal, which already had a small population, had to lose people.

By this time, the Ottoman conquests in the Middle East also came to an end, and began sending fleets of ships down to the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea. It was not so easy to drive out the Portuguese, but the Ottomans were still able to control the Red Sea and reopen the spice route. The flexible Venice also turned enemies into friends with the Ottomans and was able to import spices from Egypt to Europe. Portugal's monopoly lasted only half a century.

During this half-century, the Portuguese royal family through the spice trade or earned a lot of money, which is profitable for the Portuguese king can borrow a lot, but this capital is not spent in the right place. Despite the promise of trade with Asia, several Portuguese kings remained keen to wage jihad against Muslims in North Africa. European princes and nobles were warriors and aspired to show their bravery on the battlefield. Killing and setting fire to the infidels was a special spiritual value to show the glory of God. In concept, they had not yet jumped out of the feudal tradition, the proceeds of the spice trade were mostly consumed in the killing under the crusaders, overseas empires in turn were poorly run, and by the second half of the sixteenth century had been unable to make ends meet.

Portugal's maritime empire is said to be four-sided. It relied on artillery bombardment and territory throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America, a bit like the later British Empire, except that its fleet could not enter the inland rivers, and its power could not be projected inland. In terms of a large number of Portuguese settlers abroad, it was a bit like the Chinese in Southeast Asia, except that it was backed by the force of the state. With its hostility to Muslims, it also has a few hints of waging jihad, but its real purpose is not war but making money. With the risk capital it invested, it could be said that it was a primitive capital accumulation, even an experiment of initial capitalism, but it did not lead to Portugal's departure from the feudal economy.

It is not an exaggeration to say that it was an empire; the Portuguese were indeed the first Europeans to colonize Asia, but they were different from the modern Western colonizers. The latter had experienced the industrial revolution and were substantially ahead in terms of economy, technology, and organization. Europe in the sixteenth century, however, was not yet free from feudalism and was clearly behind Asia in terms of economy and technology, coveting its production but unable to get goods that could be exchanged, and could only export precious metals, aided by force. Although its merchant ships have the advantage in the sea, at the edge of Asian trade and economy. Europeans to reverse this situation, still need three hundred years.

Portugal as a model for the rise of great powers is an overstatement. It has never had an important role in Europe, and in Asia, it is confined to the coastal ports and oceans. Its geographic location was unique in that it was forced by small size and food shortages to go out and explore and find a way to get to developed regions, albeit long and costly, to obtain goods that were scarce in Europe. It did not break away from the limitations of feudalism, most of the money earned overseas was exhausted in the unnecessary holy war, neither strong countries nor rich people, and later became a backward region of Europe. However, it explored the channel, figured out the situation of the Asian coast, set an example of ocean trafficking, and inspired a series of followers - Spain, the Netherlands, England, France, and so on. From this point of view, Portugal is considered a pioneer in the modern history of Europe.

About the Creator

Bula Wali

And I forget about you long enough to forget why I needed to

Comments (1)

Nice!!! Historically, one of the most interesting lot of secrets...