Water expands once it freezes. What transpires if you prevent it?

The physics behind freezing water expansion.

The oxygen atoms in water molecules have higher electric dipole moments than the hydrogen atoms, thus the molecule is bent with the hydrogen atoms almost on the opposite side of the oxygen. This indicates that water molecules strongly attract one another electrostatically (opposite charges attract one another). The molecules like to line up in an orderly pattern, with the positively charged part of one molecule next to the negatively charged part of another molecule and so on, bound together in a hard crystal, if there isn't too much random motion of the molecules (i.e., the water isn't too hot). If the molecules have more thermal energy, they move around and release themselves from their neighbors. They still choose to adhere to They continually switch their neighbors and interact with one another as a result of their frequent movements. The liquid phase is at hand. The oxygen atoms in water molecules have higher electric dipole moments than the hydrogen atoms, thus the molecule is bent with the hydrogen atoms almost on the opposite side of the oxygen. This indicates that water molecules strongly attract one another electrostatically (opposite charges attract one another). The molecules like to line up in an orderly pattern, with the positively charged parts of one molecule next to the negatively charged parts of another molecule, and so on, kept together in a cohesive manner, if there isn't too much random motion of the molecules (i.e., the water isn't too hot).

The Mpemba effect, so named because it occurs when hot water freezes more quickly than cold water, is a recent phenomenon. It was discovered in the 1960s by a Tanzanian youngster named Erasto Mpemba and physicist Denis Osborne. They were able to see the effect, but subsequent studies have been unable to reliably produce the same outcome. Precision studies to study freezing can be influenced by numerous minute elements, and researchers frequently struggle to know if they have taken into account all confounding factors.

Water expands as it freezes, which is why ice floats, and cans and jars bulge or blow up in the freezer. On the other hand, water dissolves when it is compressed. An ice cube that is 4 degrees below freezing can resist up to 500 times atmospheric pressure before melting, but it will still melt at high pressure. What happens if you try to freeze water while it's compressed? If water expands when it freezes and melts when it's squeezed, what will happen? For example, what if you could cool water to minus zero degrees Celsius inside a pressure vessel that was incredibly robust and could not expand or contract? Below 0 degrees Celsius, water should freeze because it is not under pressure if it is liquid. But if it's frozen, it expands and puts pressure on the system, therefore it ought to melt. Therefore, it ought to freeze. Therefore, it ought to melt. You can see the issue. We seem to have struck a dilemma since the expansion that requires freezing produces the pressure that leads to melting. If by "paradox" you mean "phase diagram" - the pictures that show you a substance's phase of matter for various combinations of temperature and pressure and show whether it is solid, liquid, or gas. You can see on the phase diagram for water that, as you might assume, when water is cooled down, it changes from a liquid to a solid under normal air pressure.

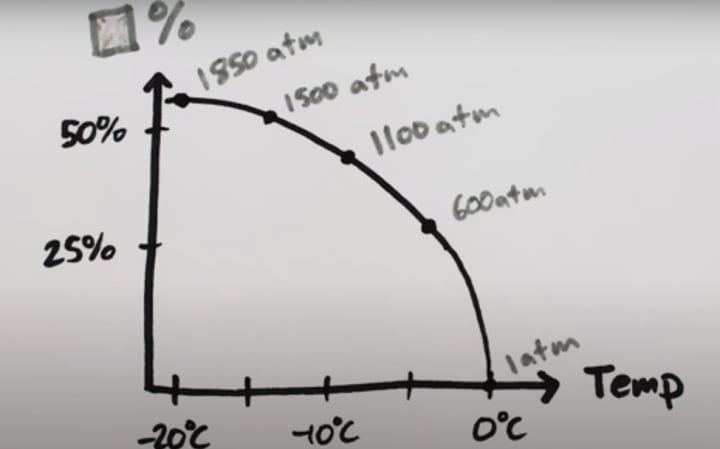

Water freezes solid at minus 4 degrees Celsius and atmospheric pressure, but when the pressure is raised, the solid water thaws out to become liquid again. What happens if you prevent the water from expanding when it freezes? The water wants to freeze when the temperature drops below 0 degrees Celsius, but only some of it can since any frozen chunks expand, forcing the container till at last the pressure is high enough to prevent any additional liquid water from freezing at that temperature! Following the liquid-solid transition line in the direction of the phase diagram, Once the pressure has built back up enough to prevent any additional liquid water from freezing, cooling the container any further will allow a small number of additional water droplets to freeze and grow. So forth. The percentage of ice and strain inside the container rises as the container cools.

This graph displays the ratio of ice to liquid water as a set volume of water is cooled to various degrees. Whether the container ever totally freezes to ice is debatable. The remaining liquid water can, however, freeze into a distinct phase of ice, known as ice III, when the temperature is low enough and the pressure is high enough, as shown by the phase diagram once more. Additionally, when it freezes, ice III shrinks and gets denser, freeing up more space and allowing the entire container to solidify, though some of it will still be ice Ih, our typical ice, and some will be ice III. Therefore, the water phase is not as irrational as it turns out.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.