The Man Who Inflated the Universe

Working late one night, Alan Guth struck upon a solution to the birth of the cosmos. Until then, he’d had trouble holding down a job.

ALAN GUTH still finds it amazing that he can understand anything about the first few moments of the Big Bang. But he shouldn’t — he was there.

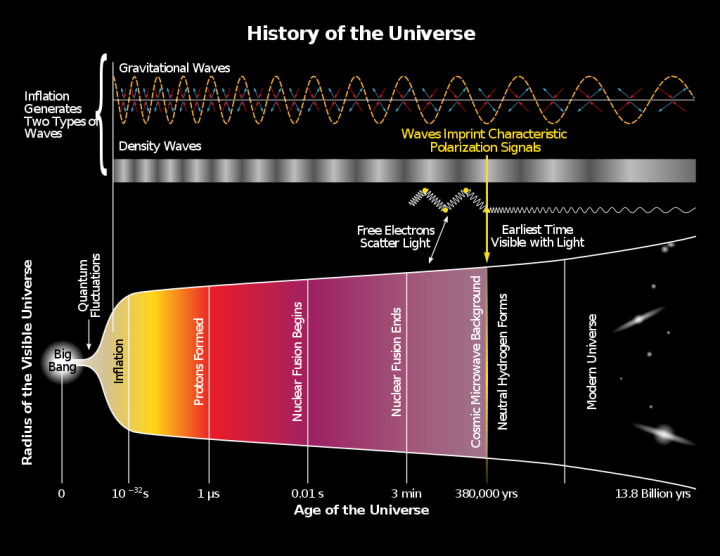

About 13.8 billion years ago, when the universe was a hundredth of a billionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second old, it underwent an incredible growth spurt, doubling in size more than 60 times in a split second. This cosmic fireball quickly slowed, then — after about 380,000 years — cooled enough for electrons to combine with nuclei and form atoms. This liberated photons of light from surrounding interference and made the universe suddenly visible.

Somewhere between 150 million and 1 billion years later, gravity drove enough clumps of gas to collapse inward that they formed the first stars. The intense heat and pressure deep within these stars acted like thermonuclear furnaces, converting the only matter that existed — hydrogen, helium and lithium — into heavier elements like carbon, iron and nickel.

And Alan Guth.

Not the astrophysicist himself, who sits before me in a checked blue shirt, light green chinos and tussled grey hair with a casual, toothy half-grin. But all of the oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium, phosphorus and trace elements that make up the man. The protons, neutrons and electrons of which those elements are made — themselves composed of subatomic fermions like quarks and leptons — were made in that early universe.

“I find it absolutely amazing,” Guth, a professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston, tells me. “I mean, we’re making theories about what was happening in the universe at 10⁻³⁸ seconds — which is totally off scale, way beyond our experience. And nonetheless these predictions turned out to describe the fluctuations of the cosmic background radiation to incredible precision.”

For a giant of astrophysics, the 67-year-old is subdued and unassuming. It’s not just his shaggy haircut that dates from the 1970s; so does the theory that made him famous. Our universe today is remarkably even in structure. Guth’s explanation? A titanic growth spurt in the split second after its birth that inflated it like a balloon, leaving it smooth and even. He dubbed his theory “cosmic inflation”.

And yet, this is a man who considers his PhD a failure. At the time he made his astounding discovery, he’d been stuck in the lower echelons as an untenured ‘post-doc’ for years. “I would say my future was somewhat uncertain at that point,” he admits, adjusting his gold-rimmed glasses. “Although I didn’t worry about it a lot; I kind of thought that things would work out somehow.”

In his case, it did — spectacularly. But it was a close-run thing.

Thanks to a doing a bachelor’s, a master’s and then a doctorate while at MIT, Guth was deferred from being drafted for the Vietnam War long enough for conscription to end in 1972, the year he graduated. But his doctoral thesis that same year, on how quarks combine to form the elementary particles that we observe, relied on the then-popular belief that subatomic quarks were extremely heavy. Unfortunately, the new theory of quantum chromodynamics emerged shortly after, rendering the idea of heavy quarks — and Guth’s PhD thesis — obsolete.

Now married to his high school sweetheart, Susan Tisch, he had a hard time landing a permanent job: over the next nine years, he took post-doctoral research positions at Princeton, then Columbia, then Cornell, eventually winding up at Stanford University’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory near San Francisco.

Over all of that time, his work — mostly on abstract mathematical problems — had nevertheless ranged from subatomic particles to the Big Bang. But it was at SLAC that all of this came together and he hit on the idea of cosmic inflation. He modestly describes it as “being at the right place at the right time.”

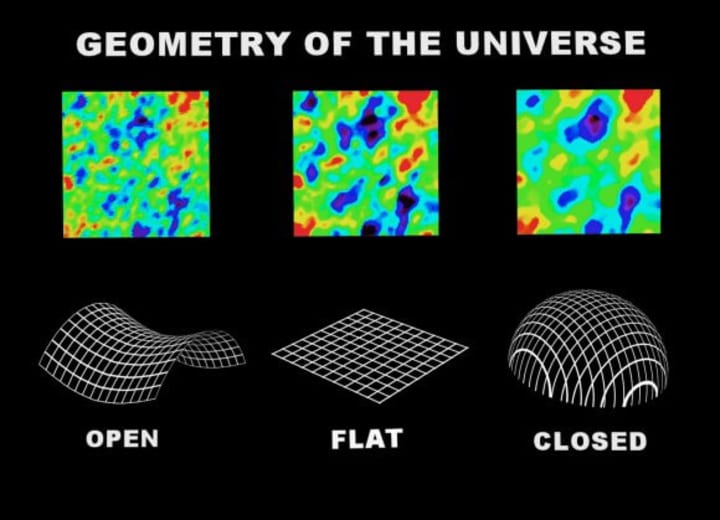

The problem plaguing physicists in the 1970s was the universe was just too perfect. The Big Bang was a compelling description of how it began, but for this to lead to what we see today, the density of matter and energy needed to be a very precise value — to an accuracy of 15 decimal places — or else the universe would either blast itself apart or collapse on itself. This was known as the ‘flatness problem’.

Another difficulty was the ‘horizon problem’: the two edges of the universe are almost 28 billion light-years apart, yet across all of that distance, the temperature is remarkably uniform, to within 0.007%. Since nothing can move faster than light, heat radiation could not have travelled between these horizons to even out the difference. Physicists were stumped.

An open universe would blast itself apart; a closed one would collapse on itself; anything but a flat universe with a very precise value for the density of matter and energy would cause distortions in the data astronomers were seeing (NASA/WMAP)

Neither of these problems were on the mind of Henry Tye, a fellow postdoctoral physicist at Cornell, who convinced Guth to work on equations that might predict the number of magnetic monopoles in the early universe. Magnets have two poles, but exotic beasts with a single pole are theoretically possible, according to the famous equations of the 19th century Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell which form the foundation of classical electromagnetism and optics. However, monopoles have yet to be seen in today’s universe — but if the early universe was superhot, many monopoles would likely have been produced.

Guth and Tye set about calculating how many. Their answer was surprising: even today, the universe should be littered with magnetic monopoles that no-one has ever seen. What’s more, the monopoles would be so gargantuan that the universe would slow down extremely fast after the Big Bang — making it just 10,000 years old, instead of 13.8 billion. “So that was clearly an impossible prediction,” Guth recalls.

He and Tye began to search for explanations that avoided the overproduction of monopoles. What if the universe cooled extremely quickly after the Big Bang, reducing the emergence of so many monopoles, they wondered? Working in the home office of his rented house one night in late 1979, Guth set about doing the numbers, and found that this did indeed skirt the monopoles and the age of the universe problem.

But at 2am that same night, he had a flash of insight. “Such a large amount of supercooling would cause the universe to expand exponentially. And I realised that this would solve the flatness problem,” he recalls. In his notebook that night, he scribbled “spectacular realisation”, and put two bold rectangles around it.

It was the birth of the theory of cosmic inflation. The next morning, he cycled to SLAC in record time. “I was very worried that there’d be some gigantic flaw, so I was very anxious to bounce the idea off colleagues to see if people could poke holes in it.”

However, his idea held up. In fact, from discussions with physicists in the SLAC cafeteria over the following weeks, it became obvious that inflation not only had legs, but also nicely solved the horizon problem as well.

“The universe was all packed together cheek-by-jowl at subatomic distances before expanding wildly, so inflation neatly bridged the world of the very small and the world of the unimaginably large, tying them together. So I became all the more excited,” he says.

Guth was suddenly in demand. From January 1980, he began speaking about his idea at universities and research institutes, inviting comment and criticism from the audience. He had always been slow to write up a scientific paper, but in this case, he had good cause: while he could explain how inflation began, he couldn’t make it end in a way that allowed stars and galaxies to form.

Plus, his postdoc was coming to a close and he needed to find a job again — although this time. the offers began coming to him. In April, after a day of job interviews, he had dinner at a Chinese restaurant. The fortune cookie he opened read: ‘An exciting opportunity awaits you if you are not too timid.’

What Guth really wanted was to go back at MIT, but there were no jobs on offer. Emboldened by his newfound cachet, he contacted a friend at his alma mater, letting him know he was entertaining a host of job offers but would really prefer to work in Boston. A day later, Guth had his job offer. “My wife was very happy,” he smiles.

By June, he’d finally completed his calculations on how inflation ended, but he wasn’t pleased — it predicted a lumpy universe, which is not what astronomers were seeing. He decided to publish his paper anyway, and it appeared in January 1981. In it, he argued that it was a powerful explanation despite the unsatisfying ending, and urged others to find ways to make the idea of cosmic inflation work.

There was already a lot of excitement — reports of his talks on inflation had been circulating in the physics community — but no-one had a ready answer. There were several attempts, but it actually took years for Guth’s challenge to be answered.

It finally came from Russian physicist Andrei Linde, then at the Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow, who in 1983 proposed a revamped approach in which the universe gracefully exits from the exponential expansion without producing a wildly clumpy structure. This electrified physicists, and soon became the prototype of modern inflationary models.

It also suggested that our universe is just one of many inflationary universes that have sprouted into being; that there might be a multiverse of all possible types existing, and still being created.

In cracking the problem, Linde was inspired by the work of fellow Russian Alexei Starobinsky of the Landau Institute of Theoretical Physics in Moscow, who in 1980 independently postulated exponential expansion, although driven by a different mechanism: quantum gravity effects.

Published in Russian, Starobinsky’s paper was unknown to Guth and others in the West, and had not addressed either the flatness and horizon problems as Guth had. Nevertheless, it was pivotal — and led all three men to win the US$1 million Kavli Prize in Astrophysics in 2014, given at a ceremony in Oslo by Norway’s king and modelled on the Nobel Prizes.

That was where I caught up with Guth and Linde. Over coffee at the Grand Hotel in Oslo — the same place where playwright Henrik Ibsen used to eat every day — Guth gushed about how Linde closed the loop: “My version of inflation did not work. Andrei made it work,” he said.

Linde, an ebullient man with windswept white hair who is now a professor of physics at Stanford, credits Guth with “a tremendous change in perspective” in physics. “Before the theory of inflation, everyone thought that quantum mechanics had an effect at very small scales, but at large scales it was considered not to be relevant,” he told me.

“But we learned that the largest objects in the universe — galaxies — were produced by quantum fluctuations.” Not so long ago, “this would have sounded like a crazy idea, one that’s good for science fiction books but not for physics. Yet you go and measure, and everything just fits into this science fiction picture. It’s just amazing.”

Starobinsky, a greying and bespectacled man with bushy eyebrows and a more reserved bearing whom I also met after the Kavli ceremony, agreed. “With this theory, cosmology becomes more like other areas of physics, it becomes predictive — we can predict what we see today with great accuracy. That’s very exciting.”

All three admit to still being astounded that humans can understand anything about what the universe was like when it was, as Starobinsky put it, “unimaginably small, less than 0.0000000000000000000000000001 centimetres across. That’s 27 zeros between the decimal point and the 1!”

Today inflation theory has been validated many times over through measurements taken by the WMAP spacecraft and other experiments that map the cosmic microwave background — the ancient echo of the light released from the Big Bang.

The first direct observation of gravitational waves was announced in February 2016. Five months earlier, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the United States — comprising of two enormous and exceptionally sensitive instruments located 3,002 kilometres apart (one in Hanford, in southeastern Washington state, and the other in Baton Rouge, Louisiana) — had observed the merger of a pair of black holes about 1.3 billion light-years away.

This was later confirmed by Virgo, an European interferometer made up of two arms that are three kilometres long and located in Santo Stefano a Macerata, near the city of Pisa, Italy.

The news rocked the physics world, and excited Guth, Linde and Starobinsky, for it opened the door to one day seeing the tell-tale echoes of inflation in fabric of the cosmos: space-time would have ‘bounced’ in response to the shock, also producing gravity waves.

Gravitational waves were predicted by Albert Einstein’s 1916 Theory of General Relativity but are exceptionally feeble and difficult to detect, requiring instruments sensitive enough to detect a ripple smaller than the width of an atomic nucleus. Despite decades of searches using increasingly sophisticated instrumentation, no conclusive evidence had ever been seen until this discovery.

Since then, LIGO and Virgo have reported more gravitational wave observations from merging black hole binaries, and in October 2017, they announced the first ever detection of gravity waves from the merger of neutron stars.

Directly measuring the primordial gravitational waves would not only be further validation of inflation theory, but offer hard numbers to explain how the universe operates from the cosmic to the quantum scale. “Detection of gravity waves could point to the unification of several forces of nature,” says cosmologist Lawrence Krauss of Arizona State University. “It might even provide compelling — though indirect — evidence of the existence of other universes.”

Excited as Guth is by the prospect, it also ruffles him when journalists dub such a potential find ‘the smoking gun’ that would prove cosmic inflation. “When people say that gravitational waves would be ‘the smoking gun’ for inflation, my response is that I thought the room was pretty filled with smoke already,” he quipped.

For a man who began his career studying subatomic particles and ended up producing a ‘failed’ PhD, then endured years of the insecurity of revolving postdoc positions, Guth has done rather well out of cosmology: when he began in the field, theories explaining the early universe were a chaotic mess. Through hard work and a bit of luck, he struck on a solution that helped make it much neater, more ordered.

Which is ironic, really, considering his office is famously messy: among the smattering of awards he’s picked up over the years is one given by The Boston Globe for the messiest office in town, nominated by colleagues who hoped it would shame him into tidying up.

“It’s still pretty messy,” he admitted. He seemed amused by the honour. Perhaps he needs the chaos for order to arise.

Like this story? Please click the ♥︎ below, or send me a tip. And thanks 😊

About the Creator

Wilson da Silva

Wilson da Silva is a science journalist in Sydney | www.wilsondasilva.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.