MEDICAL CARE IN VICTORIAN LONDON

Fifty-seven of every 100 children in working-class families were dead by five years of age

During the Victorian age, the UK became a world power. The industrial revolution had started, and a lot of tradesmen took a backseat to mass production in factories. This was a major change for most of the agricultural towns in England. These rapid changes brought new wealth to some a crushing poverty to others and leading to very high rates of child mortality in London and other parts of the UK.

Often working for twelve hours a day, tired children would return home to not much of a meal in an overcrowded slum where outbreaks of disease were common. Scarlet fever, tuberculosis, typhus and typhoid are now rare, but these were untreatable killers 150 years ago. Living in such terrible conditions meant poor children were weak, malnourished, and unable to fight off illness.

These days, nearly 80 per cent of deaths happen in hospitals, not in the home, so it removes us from this process. In mid-nineteenth-century London, the average life span for middle to upper-class males was 44 years, 25 for a tradesman and 22 for a labourer. Fifty-seven of every 100 children in working-class families were dead by five years of age.

The environment throughout London itself was atrocious. The blackened rain that fell from the sky from the smog, which hovered over London and inadequate sewage systems that poisoned water sources, created outbreaks of disease. When women who were pregnant became ill, there was a higher probability their child would be stillborn or develop a complication. Even if the baby was OK at birth, their lungs were developing and could be overwhelmed by the chemicals in the air which could bring diseases to the child as well.

Death was a common visitor to Victorian households, and the younger a child was, the more vulnerable it would be. Tuberculosis was also a common killer and by the mid-19th century, it accounted for 60,000 children’s deaths per year.

Before the epidemic of 1845, they thought rancid food caused cholera. As one can imagine, the medicine for this included avoidance of the foods suspected of spreading the disease. Of course, through what we know today, this is undeniably ridiculous. However, their lack of medical knowledge made these causes believable.

The early Victorian medical practises were a world away from what we are used to seeing today. In the first half of Victoria’s reign, treatments didn’t evolve the way they were expected to. Victorian physicians did have some understanding of anatomy. However, their ideas of the nervous system and understanding of blood was a far cry from what is understood today.

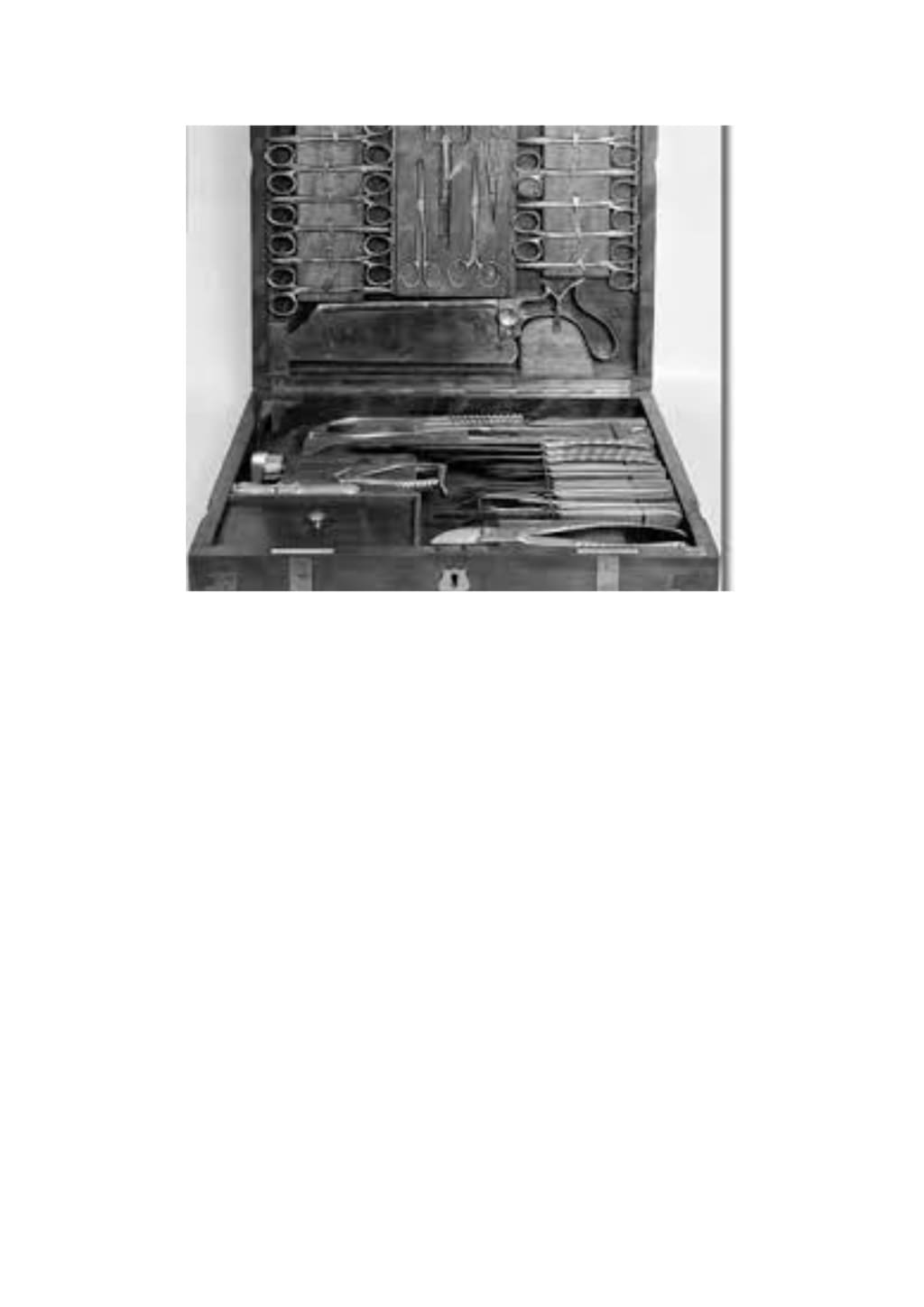

Surgery was another place the Victorians struggled on. In the early Victorian era, they performed surgery with no anaesthetic. A skilled surgeon could amputate most limbs in under a minute, often the blood loss and pain would kill the patient before the surgery was completed. During these times, the mortality rate was, on average, one in four. As the Victorian era went on, pseudo-anaesthesia was introduced: alcohol and opiates, though these did little in the way of making the pain at least tolerable. Surgery was often the last resort due to not only the pain and suffering the patient would go through, but also a surgeon would often have to deal with a patient wriggling and squirming with fear and pain. Some patients also tried to escape. Therefore, surgery was only used if they thought no other treatment would work.

During the later Victorian years, medical improvements were vast; the practises were more recognisable to what we are familiar with today. These developments and improvements included better microscopes and ophthalmoscopes, which revealed micro-organisms.

During the infamous cholera outbreak of 1854, which was thought to be caused because dirty air, Dr John Snow established that contaminated water caused the epidemic from a public pump in crowded Soho. This made doctors aware of the effects cleanliness and sanitation had on the health of others. They understood more about the causes of illnesses and how to avoid them more appropriately.

Much greater improvements, in terms of cleanliness and sterilisation, happened in the late 1800s with dressings allowing wounds to heal healthily, and metal instruments that could be sterilised. They then replaced wood and bone handled tools that could never be sterilised so easily. With the understanding of bacteria, the diagnosis of a person’s illness became more reliable, especially when the patient had surgery.

About the Creator

Paul Asling

I share a special love for London, both new and old. I began writing fiction at 40, with most of my books and stories set in London.

MY WRITING WILL MAKE YOU LAUGH, CRY, AND HAVE YOU GRIPPED THROUGHOUT.

paulaslingauthor.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.