How I Finally Understood the Famous Monty Hall Problem

Lessons I learned from the brain teaser that almost broke me

Imagine you are the contestant on a game show. There are three doors that you can choose from. Behind two of them are goats. Behind one is a new car.

Setting aside the possibility that some people prefer goats to new cars (what you do in your private life is none of my business) the goal is to pick the right door - the one with the car. You choose door number one and Monty Hall, the game show host, opens a door. But instead of opening door #1, he opens #2. It's a goat.

Now you must choose again. But Monty Hall gives you the option of sticking with door #1 or switching to door #3. What should you do?

Most people naturally assume that it makes no sense to switch (or that it doesn't matter) because the odds are 50/50 that either door has the car.

But that assumption is wrong.

The reason is that the odds of picking the right door on the first try are 1 in 3. That means that there is a 2/3 probability that the car is behind one of the remaining doors. But once door #2 is eliminated, there is still a 2/3 probability that the door you didn't pick is correct. And with #2 no longer a viable option, the probability that #3 has the car must be 2/3. The following YouTube video explains it in a little more detail.

Still not convinced? Neither was I

If you find yourself unconvinced by the above explanation, you are far from alone. The intuition to see the odds as 50/50 is irresistibly strong. The Journal of Belgian Association for Psychological Science has studied it in depth. In a 2018 study, they concluded that "the optimal solution to the MHD is to switch." The study itself sought to understand "why humans systematically cannot react optimally to the MHD or cannot understand it."

I was also one of the people who found the "switch solution" utterly mind-boggling. After thinking about it for three days straight, I thought I had a pretty convincing argument against it.

My reasoning was that however the situation may have started, the only relevant information at hand is that there are two doors left, one containing a goat and one containing a car. The situation can be thought of as two different games. In the first game, the odds of success are 1 in 3. In the second game, they are 50/50.

I even broke it down into a syllogism:

Premise 1: A 50/50 success probability exists when there are only two choices, and only one of them will be correct.

Premise 2: Now that door number 2 is eliminated, there are only two choices.

Conclusion: there is a 50/50 success probability.

You can't argue with a rock-solid deductive argument like that.

Or can you?

The lightbulb moment

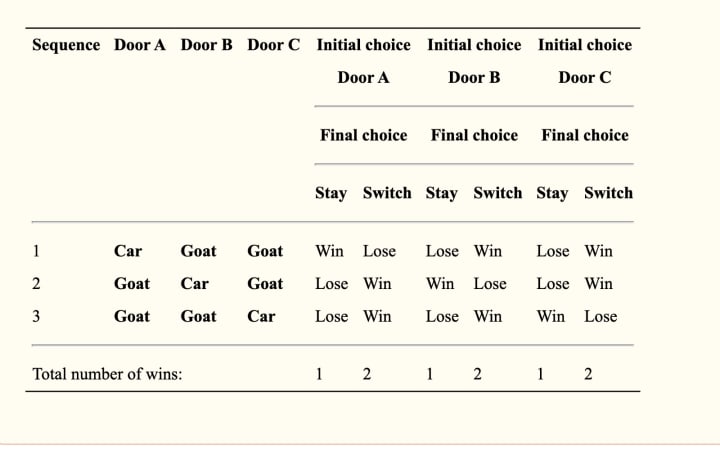

I was feeling pretty sure of myself until I read the JBAP study and came across the following chart.

The chart is tricky at first glance, but if you look at the bottom, you can see that switching results in a greater number of wins. You can't argue with empirical results and the results are clear: switching increases your likelihood of success.

Once I thought about it for a while, I realized where the flaw was in my thinking.

I thought that my previous choice of door #1 had no bearing on the facts at hand: that the final choice involves two doors and two possible results. But my initial choice of door #1 was influenced by the fact that there were 3 doors to begin with. And that choice prompted Monty Hall to open a door that he knew would contain a goat. So the facts at hand cannot be considered independently of the rest of the game.

Here's how I break it down for myself, step by step:

Since the game must be considered as a whole, the 1/3 probability of picking the correct door on the first try cannot be dismissed even when there are two doors left.

Since that probability cannot be dismissed, then the original 2/3 success probability for the doors I didn't pick still stands.

Finally, with door #2 no longer viable, I have a 2/3 success probability with the one viable option that I didn't initially choose: door #3.

But what about the air-tight syllogism?

To anyone who has taken an introductory course in logic, it's well known that with a deductive argument, if both premises are true, then the conclusion necessarily follows. So one or both of the premises must be false.

Premise 1: A 50/50 success probability exists when there are only two choices, and only one of them will be correct

Premise 2: (Now that door number 2 is eliminated) there are only two choices

Premise 2 is false because it says that there are only two choices when there are, in fact, three in total. And this is where it makes your brain hurt because you want to scream and say, "not anymore! There are only two choices now!" But the existence of those two choices is a direct result of the initial 3-door setup of the game. So it's illogical to dismiss the initial setup as irrelevant.

Also, door #2 is, technically, still a possible choice. We take it for granted that we have the intelligence to see that door #2 is the wrong choice, given our objective. But what we might not see is that when we make that determination, we do so as a part of a probability calculus in which we factor in three doors, two goats, one car, and the discovery of one of the goats behind one of those doors.

To a certain extent, it may be that the intuition to see the odds as 50/50 is an example of humans being too smart for their own good.

Final Thoughts

I think there is a lesson in the Monty Hall problem that goes deeper than mathematics. It shows us that, at times, even our deepest intuitions can be wrong. We can have what we think are fool-proof arguments in favor of our way of thinking and yet still be mistaken because our thinking is based on faulty assumptions.

It's as Peter Singer says:

"Philosophy ought to question the basic assumptions of the age. Thinking through, critically and carefully, what most of us take for granted is, I believe, the chief task of philosophy, and the task that makes philosophy a worthwhile activity."

And since we know that ideas have consequences, it makes sense for us to question our assumptions, not merely as an intellectual exercise, but for the sake of finding truth and putting truth into action.

About the Creator

Carmelo San Paolo

Writer of pithy ponderings, passionate polemics, and unsolicited advice

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.