Before Joseph Stalin Was Dictator, He May Have Been A Spy For The Tsar

Assessing the evidence of Stalin's shady past

In the final years of the dying Russian Empire, the Tsar’s intelligence agency, known as the Okhrana, were working around the clock uncovering assassination plots, arresting revolutionaries, and keeping an eye on dangerous characters.

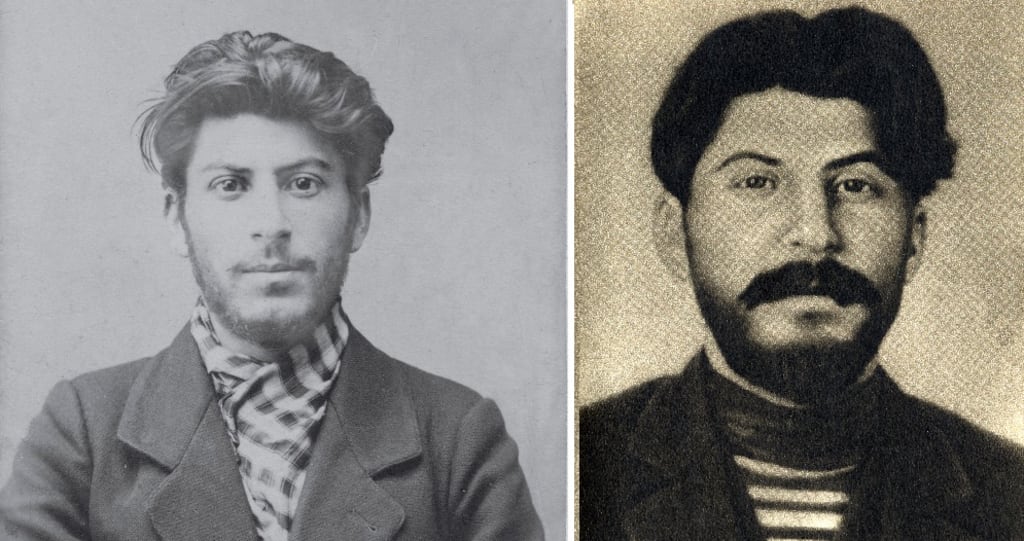

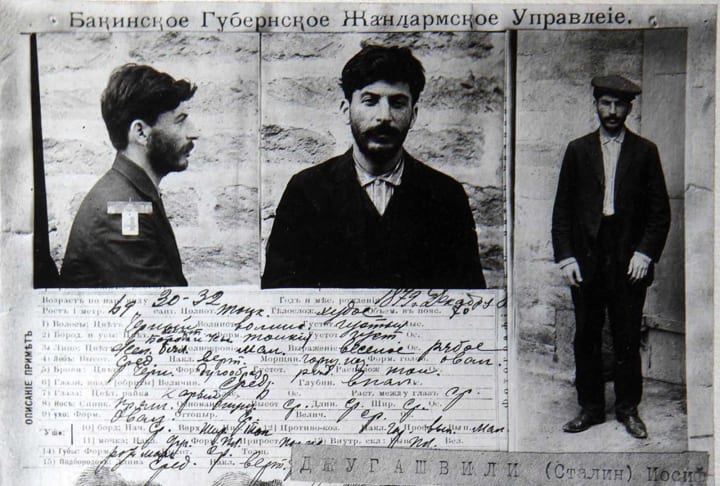

One name frequently on their radar was one Josef Vissarionovich Djugashvili, a Georgian man of many names: “Soso” to his intimates, “Koba” to his friends, “The Milkman” in the Okhrana’s coded reports, and plenty of personal pen names in his own letters. From 1912 he started calling himself Joseph Stalin, and became brutal dictator of the Soviet Union for 30 years.

The Okhrana were certainly watching the right man.

As early as 1901, as a 23-year-old Stalin was beginning his career, he was already identifying Okhrana spies and wasn’t afraid to get his hands bloody. He was regularly involved in strikes, violent demonstrations, and provoked unrest amongst workers. This sort of behaviour landed him in prison in 1902 and exile in 1903, from which he duly escaped and joined up with the newly formed Bolshevik Party shortly after.

He would go on to be arrested six more times until 1913, with the mildness of his sentencing often being the basis of allegations he was an agent provocateur or a spy, let off by his employers.

These allegations plagued his reputation for years.

The Okhrana and “The Milkman”

Despite ultimately failing in their mission to prevent revolution, the Okhrana, set up in response to Tsar Alexander II’s assassination in 1881, had significant success in infiltrating underground groups, arresting revolutionaries, and ultimately slowing the inevitable tide, allowing the Russian Empire to limp on a further 30 or so years until its fall in 1917.

One successful tactic used by the Okhrana was the employ of insiders, moles, double-agents and spies, not just getting information but also spreading paranoia and distrust. Okhrana agents were rampant throughout underground networks and were a constant source of trouble for the revolutionaries. Many times a plot would be foiled at the last moment when Okhrana agents would swoop in and make arrests.

The early years of the Bolshevik Party were tense.

Stalin sufficiently impressed Bolshevik higher-ups with his work in Baku (in modern day Azerbaijan) and Tiflis (now Tbilisi, in modern day Georgia, back then both part of the Russian Empire), and was stayed in regular contact. His role from around 1908 was to rally support, spread Bolshevik writings, and raise money for the Party.

But he was also in charge of intelligence and counter intelligence from around 1908, at least in the Baku/Tiflis region, and a large part of his role during this time was spent grooming potential Okhrana agents and police officers. Sometimes they were sympathisers to the Bolshevik cause, other times they just wanted money.

It is often the case that a man who embroils himself in such tactics ends up being accused himself, which is exactly what happened. It certainly is a dangerous game to play.

The accusations

Stalin was careful to protect his sources of information. He knew revealing too much would uncover his informants and put them, and his Party, at risk. And this secrecy inevitably led some to raise eyebrows and grow suspicious.

There were occasions when Soso would burst in to a room unexpectedly and tell his men they needed to leave right away, allowing them to narrowly avoid a bust. Other times he seemed aware of arrests before they had even happened. His men wondered, how did he know so much?

It was in 1909 that this suspicion reached its peak, as Stalin’s valuable printing press was raided. He received this information late from his own contacts and was therefore unable to prevent it from happening. The bust resulted in the arrest of one of his key men, and Stalin had to bribe police to avoid arrest himself.

Fingers began pointing. How did the Okhrana find the location of the printing press? Who had betrayed them? Stalin was furious.

Even at this early stage of his career Stalin was ruthless, and it was usual for anyone strongly suspected of treachery to be quietly killed. What followed was a crazed witch hunt, exactly what the Okhrana wanted. Stalin decided there were five traitors in his ranks and wrote a list of names, but we now know that none of those accused were on the Okhrana’s payroll.

As it turns out, his ranks did contain two undercover Okhrana agents, but they were never suspected by Stalin.

While the witch hunt continued and the problem of treachery was clearly still not resolved, members of the rival Menshevik Party, recognising Stalin was always the one doing the pointing and had ample contacts within the agency, naturally began accusing him. Some Bolsheviks did the same.

It was understandable that Stalin should be accused. Not only because of his connections with Okhrana agents that supplied him with information, but also because of his reputation. Ruthless and morally corrupt, his early career was one of bank robberies, kidnappings, extortion and murder. Few of the revolutionaries were saints, but Stalin was in a league of his own.

Was he capable of betraying his own Party though? And what of his mild punishment the multiple times he was arrested?

Well, it turns out light sentencing of these revolutionary crimes was fairly common place, with the Okhrana being excellent at finding dangerous individuals, but the Tsar’s officials being terrible at punishing them.

Many troublemakers would be shipped off to Siberian exile for a determinate amount of time, as Stalin was several times. Most treated it as a holiday and relaxed in a quiet village out East until the heat died down. Many were joined by friends and family, and nothing other than distance was keeping them there. When they had enough, regardless of their sentence, they headed back to where the action was.

The leniency shown to Stalin was certainly not uncommon.

The Eremin Letter

This suspicion was never acted upon by the Party, suggesting it was never taken seriously by those who mattered, but they continued for much of the Party’s early struggles. As the Tsar’s power weakened, however, so did the Okhrana’s. The February Revolution in 1917 shifted priorities.

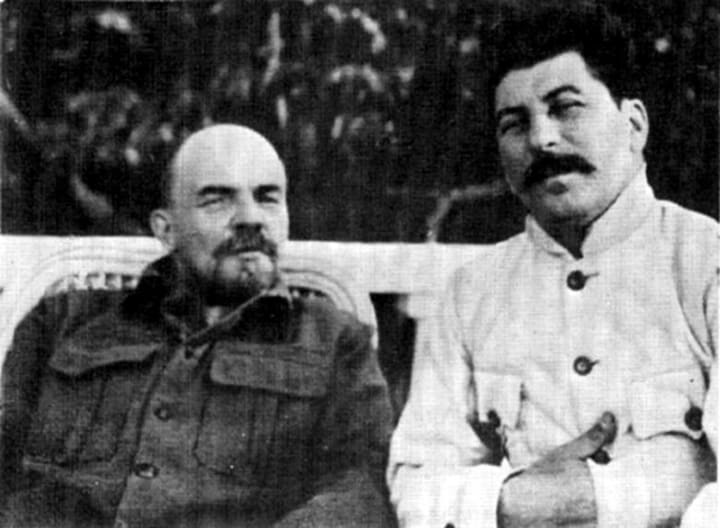

Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication resulted in a wild power grab and civil war between warring factions, as a new post-monarchist nation emerged for the first time in hundreds of years, eventually under the lead of Lenin. By now, stronger and more stable, the finger pointing had subsided. It never stopped, but Stalin, at least, was not accused.

After Lenin’s died, Stalin took his place. He reached the position of General Secretary of the Soviet Union in 1922, then consolidated his power to become dictator from 1930 until his death.

In 1956, three years after Stalin’s death, a letter resurfaced from the ‘20s, throwing new light on the old accusations.

Supposedly written by one Colonel Eremin, head of the Tiflis Okhrana from 1908, it reported that Stalin provided “accurate but occasional work” to the Okhrana during the years 1906–1912, but when he became a member of the Central Committee he broke the relationship off completely.

Many have pointed to this letter as proof. Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, meanwhile, had the document investigated when it was brought to his attention and found it to be a forgery, with most modern historians doing the same.

No other evidence exists in the case against Stalin, but many explain this away by pointing to the purges prior to World War II: this, they say, was his attempts to cover his tracks.

Stalin was notorious for his censoring and destruction of anything damaging to his cult of personality. His paranoia and anger at suspected traitors, which began in 1909, stayed with him the rest of his life. In three years, somewhere in the region of one million people were killed during the Great Terror, many of whom, some say, may have had damaging information that posed a threat to his power.

But some Okhrana documents still exist mentioning Stalin, so did he choose to leave some but only destroy the ones which exposed him? Or, while damaging reports were found, were those less so just missed?

The fact this Eremin letter was printed in ’50s America during the Cold War should be enough to make us doubt its authenticity. As many have said, proving the treachery of Communism’s leading man would be enough to discredit the entire ideology — something they longed to do.

Conclusion

The verdict, then? Stalin was almost certainly not a spy.

The accusations against him were typically made by his enemies, and in a time of paranoia and treachery, he was not the only one to be suspected. Those who were the most successful needed strong intelligence connections, and Stalin certainly had those. He had moles and informants within the Okhrana supplying him with a stream of information, and that allowed for his added secrecy and insider information, which was just fuel to the fire.

It certainly was a dangerous game that Stalin was playing, but it was a necessary one. If his struggling Party was to not only succeed, but also simply survive, they had to get the upper hand somehow.

One point raised by modern historians is Stalin’s relative poverty during this period. Despite arranging and participating in multiple fund raising bank robberies, kidnappings and extortion, he kept none of the money for himself and lived as a pauper. Most Okhrana double-agents, it should go without saying, didn’t work for free. If Stalin was an agent provocateur, would that not have been evidenced in his lifestyle in some way?

Even if he was careful, some evidence would surely exist, whether that be secret police reports watching his movements, private letters to family, friends and lovers, or something else. There was no sign that Stalin had any personal wealth whatsoever during this time, suggesting he was either doing the dangerous, underhanded work out of charity, or he was not doing it at all.

If he was a double-agent, then he was the most successful double-agent in history, playing both sides against each other, leaving absolutely no evidence behind (if we dismiss the Eremin Letter as a forgery), and discarding his employers as they were no longer useful, as he rose to become leader of the Party he betrayed, with no repercussions by the Okhrana or by his colleagues who he attacked and leapfrogged on his way to the top.

The lasting accusations against Stalin, if anything, are the legacy of the Okhrana’s success.

As author Simon Sebag Montefiore put it:

The Okhrana may have failed to prevent the Russian Revolution, but they were so successful in poisoning revolutionary minds that, thirty years after the fall of the Tsars, the Bolsheviks were still killing each other in a witch hunt for nonexistent traitors.

While Stalin was a man of loose morals and vicious ruthlessness, his loyalties to Lenin and Marxism could never be in question.

* * *

About the Creator

R P Gibson

British writer of history, humour and occasional other stuff. I'll never use a semi-colon and you can't make me. More here - https://linktr.ee/rpgibson

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.