Stereo and Crimes of the Future

Written and directed by David Cronenberg, 1969-1970

"Jomkin suggests that there must evolve a novel sexuality for a new species of man." — Crimes of the Future

Before he became the cinematic master of body horror, David Cronenberg was an experimental student filmmaker who turned out works very much in line with the same sort of fixations explored almost exclusively by J.G. Ballard, whose Crash he later adapted into a film, in 1997. His early films, his first two, Stereo (1969) and Crimes of the Future (1970), explore film technique in documenting the huge, yawning architectural environment of an unspecified hospital or research facility, relegating the performers of the film to almost being secondary actors in a drama defined by geometrical shape—relegating them to the roles of insectile life, pursuing strange, even inscrutable actions, ostensibly being filmed by the watchful, clinical, and coldly detached robotic eye of the viewer, who becomes the de facto research assistant to the director, who seems to have made this film by asking his performers to improvise within the framework of derangement. What was he exploring? one wonders. The environment itself dwarfs the humanity of the filmic subjects, overpowering them in its specter of geometrical dominance and dimension.

The following three short essays were written separately.

Stereo (1969)

Stereo, made in 1969, is a relentlessly dull yet still oddly compelling experimental film that takes place at an institute the location of which will be seen again in Crimes of the Future, the film Cronenberg made the following year. It seems to have been the first salvo fired, or perhaps the first neural synapse to fire, in the creative overmind of the director's idea of cinema, and what he wanted to achieve with it. For professional reasons, of course, he altered course quite early in his career—the weird, avant-garde detachment would later reemerge in films that questioned mankind's tenuous grip on sanity and morality in a future whose modifications of the body and spirit were relentless, merciless, and endemic; unstoppable. Films as disparate as Naked Lunch, Crash, eXistenZ, M. Butterfly, even The Fly, which, despite the Cronenberg grotesquerie, played to audience expectations of an entertaining film.

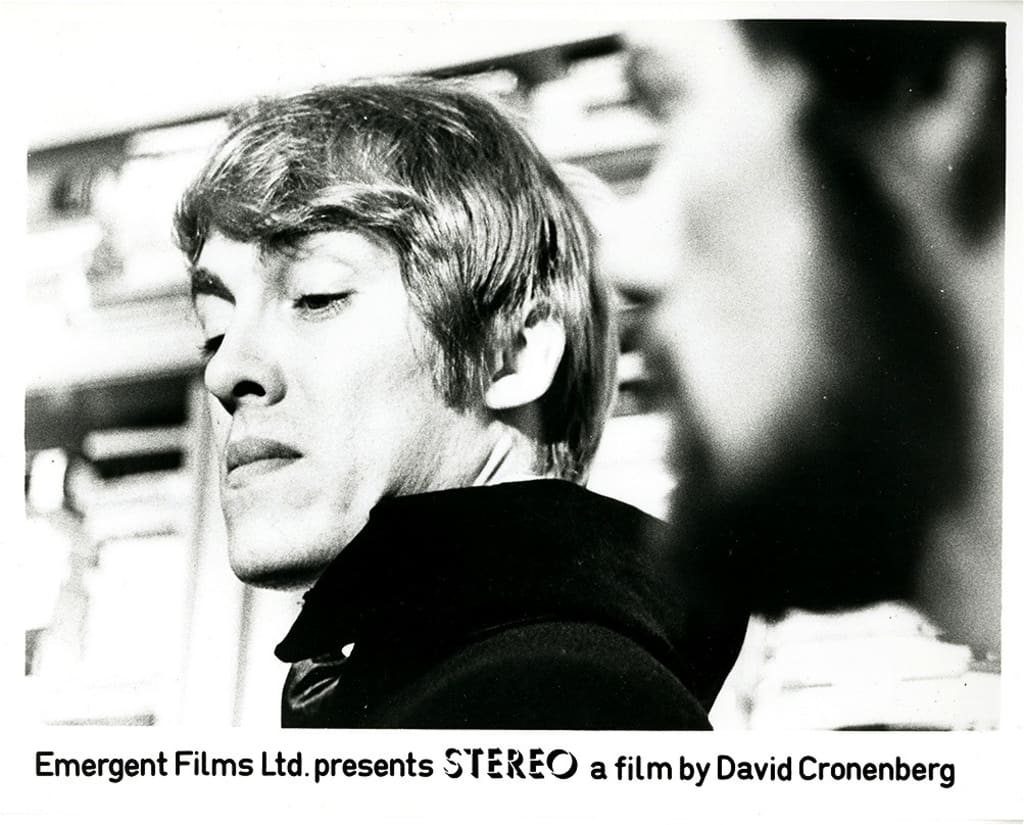

Stereo does NOT play to such expectations; in fact, it would be hard-pressed the critic who could define it in the conventional sense of a movie. The protagonist (Ronald Mlodzik) is a tall, somewhat dashing, but thoroughly dapper Englishman in a dark cloak and clothing, wandering around the grounds of an architectural, modern nightmare of an institute, and its campus, including grounds that abut a bridge over a creek (a potent, symbolic image). The film might be a satire of Scientology and like-minded “personal development” cults; the nonsensical narration, which sounds like grad students reading at random from their theses, alludes to “Dr. Stringfield,” and his experiments, groundbreaking to be sure, in telepathy and extra-sensory perception. And this is all related to the violation or co-joining of individuated telepaths in “experiential space”; and, somehow, it goes back to sex.

There is an amount of clinical nudity here, masked lovemaking, and totally anonymous personages, the actors and actresses, moving in what seems pointless fashion through the overwhelming hallways and corridors, framed at times for the best cinematic composition and perspective. The narration gives an odd jarring counterpoint to lovemaking, tea making, flirtatious orgies, and Tarot reading. But what is Cronenberg on about here? The viewer will be left wondering, by the end, why the insectile eye of the camera, so obsessed with the surface of hallways, doorways, laboratory tables, etc., felt compelled to document the living, ant-like interlopers in the great throat of officialdom represented by the architectural monstrosity, while we assume their movements and ministrations, including taking obscure pills at the end, has something to do with them being E.S.P. test subjects. It's a science-fiction concept further rendered more fantastic (i.e., inscrutable), by the unconventional unfolding of its opaque narrative. A film that will entertain few in the conventional sense.

The full title of Stereo is, BTW, “Stereo: Tile 3B of a CAEE Educational Mosaic.” The Stringfellow test subjects have reputedly been given brain surgery to aid in their erotic telepathic egress into the “experiential space.” The version I watched had NO soundtrack, with long silences between narrative breaks. I found Stockhausen most appropriate to play in another window.

Crimes of the Future (Trailer) 1970

Crimes of the Future (1970)

Crimes of the Future is a brilliant early work by the masterful chronicler of high-concept body horror and erudite, avant-garde dramas David Cronenberg, a man who explores the outer fringes of what is acceptable, of the evolution of human bodies, and even human consciousness, in the ever-evolving, shifting landscape of medical marvels, technological breakthroughs, and even mass-induced trauma and hysteria of a world slowly waking up, careening psychically toward a nexus point of evolutionary change. Along the way, he gives us plenty of grue, and a lot of gristle to chew.

Crimes of the Future, a film title he used again for what amounts to a kind of sequel, or extenuated reconceptualizing of the central, obsessional point—i.e., a world wherein a weird cancerous disease suggests evolution exploding outward into bizarre, alien organs and growths (the 2022 film reconceptualizes this organic odyssey in terms much darker, and more oriented toward a cinematic sci-fi graphic novel).

Crimes employs the detached narrative voice of J.G. Ballard, and, though there is nothing to suggest Cronenberg read Ballard prior to filming Crimes (The Atrocity Exhibition was published the same year as Crimes was released), one cannot help but be struck by the similarities between the literary and cinematic discourse—an institutional setting, a place of alienating and striking architectural structure (a place employed as if to underscore the post-modern aesthetic) is the backdrop for the bizarre, internal, dreamlike journey of a dark-suited man, “Adrian Tripod” (Ronald Mlodzik again), who invokes, roughly, the mien of the fanatical priest in Ken Russell's The Devils (Father Barré, as portrayed by actor Michael Gothard). This is “Adrian Tripod,” whose clinically detached narrative over the silent film is interspersed between an experimental soundtrack of musique concrète that invokes Pierre Henry or Pierre Schaeffer, or even the earliest experimental noise of William Bennett and Whitehouse. Which, given that the film ends with an odious suggestion of abuse—a suggestion that hangs, like the blade of a guillotine, across the oppressive final scenes, daring the audience to react in hushed, sickened outrage—seems somewhat appropriate.

Stereo Trailer

The House of Skin, at which Adrian is a researcher, or doctor, or? The narration focuses increasingly on the quest to find Antoine Rouge, a character whose invention of a poisonous cosmetics decimates the female population. Or something akin to that. The internees or test subjects at the institute are dominated by interns of Tripod, and the action seems to be largely symbolic abstractions—but can be assessed as simple improvisation on the part of the actors or directors. At least to a point. Antoine Rouge (or somebody we take to be him) emits blood, bile; his vestigial growths or evolutionary protean organs are shown to be lovingly preserved in glass jars.

There is a homoerotic and even perverse undercurrent here—foot fetishism, and a world without women which seems to demand men become homosexualized. But this is demonstrated in a manner that never delves beneath the surface in any meaningful way—offering to us only playful hints, an abstract and symbolic caress that ends in ambiguity.

The central horror of the film, the suggestion of the violation of a child actress (to be delicate), hovers over the viewer like a sickly-anticipated mirage at the end of the film. Viewers may experience horror, dread, or disgust at the way the director moves to the edge of a cliff, looking over the precipice at the Valley of Taboo.

At the end, Crimes of the Future posits an abstract revolutionary play which suggests a meta-referencing truth: obscure and absurd “plot” developments play out like fictional, improvised recreations of short dramatic actors or even patients engaging in a private therapy that we cannot understand. But that is no crime, we take it; not now, nor in the future.

Addendum: The Tarot of Stereo

At fifteen minutes in, Stereo presents presumably Stringfield (Mlodzik) and another man laying out Tarot cards. On the table are three cigarettes, all "crossed," lying across each other, and Stringfield fiddles with a baby's pacifier. On the back of the cards is the symbol of the Egyptian ankh--which, the viewer notes, has roughly the shape of the pacifier.

The cigarettes hint at pacification, oral fixation. The ankh? A symbol of the Sun, immortality, but one can't help but notice it's vaguely the same shape as the ankh. What is being implied here? Cigarettes, as an oral pacifier of course, are deadly. The Sun is number 19 in the Major Arcana. One and nine can be read as "10," reduced down to one (but also, indicating rebirth, initiation, The Fool--numbered as zero--and The Magician, numbered as "1". God manifests as The Fool, his own Divine Self incorporated as the eternally returning, fleshly experiencer of this base, carnal "reality." But flesh and spirit, as much as Two of Pentacles indicate, are an intertwined juggling act.

The first two cards seen are the Six of Cups and the Three of Wands. The Six of Cups, which depicst two children desporting in a garden, handling the cups of felicity--which here are the cups of rememberance. Or, perhaps, MEMORY. The Three of Wands represents the next step up from the "bad choices" represented by the Two of Wands--the "rock and a hard place" decision. Three of Wands intimates the ability to get done that which the Querent desires. The Querent's personal plans and visions put into action, hot on the heels of decision as exemplified by the Two.

Memory (mental acuity and the ability to transmit thought), plus, fulfillment of plans and goals.

The actual layout depicted is thus:

The Queen of Pentacles, The Moon, Three of Wands, and Six of Cups. beneath all of them, as if the Querent's Significator, is the Eight of Cups. Reading them thusly, we come to The Queen of Pentacles representing the Female Anima grasping the valued treasure, the Pentacle shield, and, next to her, The Moon--the journey into the subconscious mind; but, in this case, also the pairing of disagreeable opposites (the narrative soundtrack gives reference to homosexuality and bisexuality as preferable states to what it terms "monosexuality." And this is to be achieved, the viewer takes it, through the melding of consciousness achievable only by a telepathic state.

The Ten of Staffs is oppression, pure and simple, but can also hint at revenge, insomuch as the staves themselves are thought to be each a striking staff wherewith the Querent may seek to hit the enemies that have put him under the burden of his oppression; to punish, as it were. The Three of Wands is the ability of the Querent to manifest his desires and bring them into actualization.

Note. I suddenly realized, rewatching the film that, for some reason, I seem to have become confused about the cards laid out. Misremembering them. Here then, we have the short run-down:

Four of Swords is repose, relaxation, rest. Next, the Five of Swords sees this brief moment of respite turn into bitter, ugly, unwinnable conflict. The Four of Pentacles is a character, Querent/Questioner, who is afraid to overextend him or herself, in fear of loss, insecurity.

The Lovers is supernal romantic love; self-explanatory, really. It is a mirrored perfection of the overwhelming, overbearing toxic love proffered by The Devil. Both are equal and opposite in their effect.

At bottom, we have The Fool, the Divine Child just as much as the solar deity, The Sun, also represented by Cupid, the arrow-slinger, who rides the Divine Horse, which Christ and Krishna also ride, the White Stallion, into the rising rays of the coming Dawn, the New Epoch. The Fool begins again The Fool's Journey, being numbered as Zero, having "No Beginning and no End," the snake Ouroboros eating its own tail. Also, reincarnation.

The Second layout has an affinity for the first--the two Stringfield research subjects might be lovers, at least on the Astral, or share a "twin-flame" affinity. But their layouts indicate they have a magnetic attraction.

As noted, before the meanings behind the cards still hold for this second lay-out. The Queen of Pentacles followed by The Moon indicate a woman whose possession, in sense of self, is shaken by the journey into the subconscious. Afterward self-doubt and confusion is replaced by the realization of ambition proffered by the Three of Wands (Wands the symbol of impregnation, perpetually "greening" the environment). The Six of Cups is naivety, pure and simple; nostalgia for childhood's former state of perfection. Beneath all of them, like The Fool, who forever departs or strikes out, is the Eight of Cups, the Seeker, the one who departs, Like The Fool, for knowledge of the correct spiritual path.

Bisexuality is proffered as the correct spiritual pathway--achieved through a symbiosis, somehow, forstered purely from the interaction or interjection of one test subject into the "experiential space" of another.

One cannot but help notice the large ball with an all-seeing eye, in fortune telling parlors rendered an all-seeing eye in a palm (a symbol of importance, even great importance, to THIS author). The symbol of Universal Consciousness. The Wejet. Or, as they called it in the movie Quills: "The winking eye of God."

But perhaps they meant something different there.

Author's website

Author's YouTube

My book: Cult Films and Midnight Movies: From High Art to Low Trash Volume 1

Ebook

My book: Silent Scream! Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Metropolis, and Edison's Frankenstein--Four Novels.

Ebook

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments (1)

I am captivated by the idea of both these films. They are both very much the type of film I can become engrossed with. Thank you for bringing these to my attention as I had never heard of them before. I am going to go on over to YouTube and see if I can find the films there. I would be interested to see your take or review on THX 1138 or Videodrome - two of my favorites. Or even the cult classic Eraserhead.