Mystery of Maya 819 Day Calendar Finally Decoded

And not a day too late for cannibalism

If you are an inveterate clock-watcher or diary maniac, then this story might be of interest. I used to be ‘clinically obsessed with time’ according to my sister, but now I’m a bit more relaxed as I live on a boat and don’t usually know what day it is.

But I do know what the date is and what the phase of the moon is, as it governs the tides. And tides are a key concern to me at the moment, as I write this on the Fitzroy River in Queensland, Australia. My boat needs 2.9 metres of water to float and I ran aground last week (only for half an hour, thank Neptune!)

Dates, calendars and the moon. Important stuff for me.

Anyway, it seems the Mayan Civilization had a sophisticated calendar with an 819 day ‘year’.

Calendar context

The Maya civilization, which flourished in Central America from around 2000 BCE to the Spanish conquest in the 16th century, is well-known for their sophisticated mathematical and astronomical knowledge. One of the most intriguing aspects of their calendar system is the 819 day calendar, also known as the tzolk’in haab calendar.

What is it?

The 819 day calendar is a combination of two other calendars: the tzolk’in calendar, which is a 260 day cycle based on the movement of the moon, and the haab calendar, which is a 365 day solar cycle. The tzolk’in calendar is used for divination and religious purposes, while the haab calendar is used for agriculture and civil purposes.

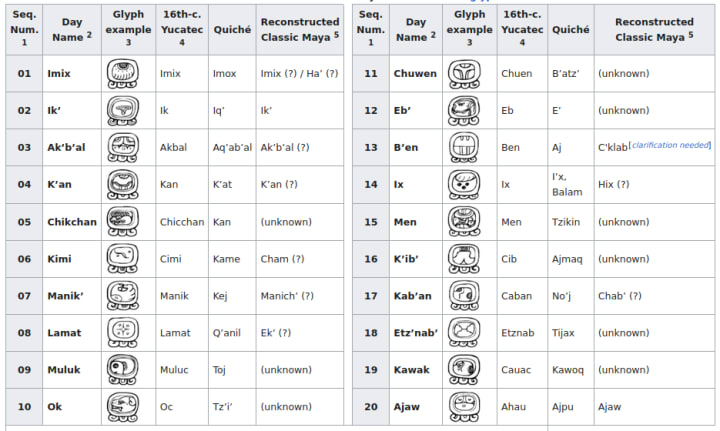

To understand the 819 day calendar, it’s important to understand the tzolk’in and haab calendars separately. The tzolk’in calendar is composed of 20 periods, each with 13 days. The periods are represented by different symbols, such as animals, elements, and gods. This gives a total of 260 days, which was believed to be the length of a human gestation period. The haab calendar is a 365 day cycle composed of 18 months with 20 days each, plus a final five-day period called Wayeb’.

The 819 day calendar is created by multiplying the 260 day tzolk’in cycle by three and the 365 day haab cycle by two. This gives a total of 780 days, which is then rounded up to 819 days. That seems like a big round up to me, but let’s move on.

The resulting calendar is used for forecasting astrological and agricultural events, such as the timing of planting and harvesting crops.

One of the unique features of the 819 day calendar is its connection to Venus, which was a significant celestial body for the Maya. Venus appears as both the morning star and the evening star, and its cycles were closely observed and recorded by the Maya astronomers. The Maya believed that Venus had a direct influence on human affairs and used it to predict important events such as wars and the rise and fall of rulers.

The Venus cycle lasts approximately 584 days, and it was believed that every 104 Venus cycles (approximately 60,100 days), Venus would return to the same position in the sky. This was known as the “Great Venus Round” and was considered a very significant event. The 819 day calendar was used to track Venus and predict when the Great Venus Round would occur.

Another important aspect of the 819 day calendar is its connection to the concept of “trecenas,” which are 13 day periods within the tzolk’in calendar. The 819 day calendar is composed of 63 trecenas, which are believed to represent different aspects of the natural world and the gods who presided over them. Each trecena has a specific symbol and is associated with a different deity or energy.

For example, the first trecena is represented by the crocodile and is associated with the god of creation and the beginning of life. The fourth trecena is represented by the jaguar and is associated with war and sacrifice. The ninth trecena is represented by the snake and is associated with transformation and healing. The Maya believed that the trecenas had a direct influence on the events of the world and used them for divination and prediction.

The 819 day calendar was also used to track the movements of other celestial bodies, such as the sun and the moon. The Maya were skilled astronomers and were able to predict astronomical events such as eclipses and the movements of planets with a high degree of accuracy. They used this knowledge to create calendars that could be used for both practical and spiritual purposes. Like sacrificing virgins, Spanish sailors and children (allegedly). And eating them.

So what’s new now?

Some aspects of the calendar have puzzled scientists for many years, never being fully explained. But now it has been fully decoded by researchers John H. Linden and Victoria R. Bricker in a recent study.

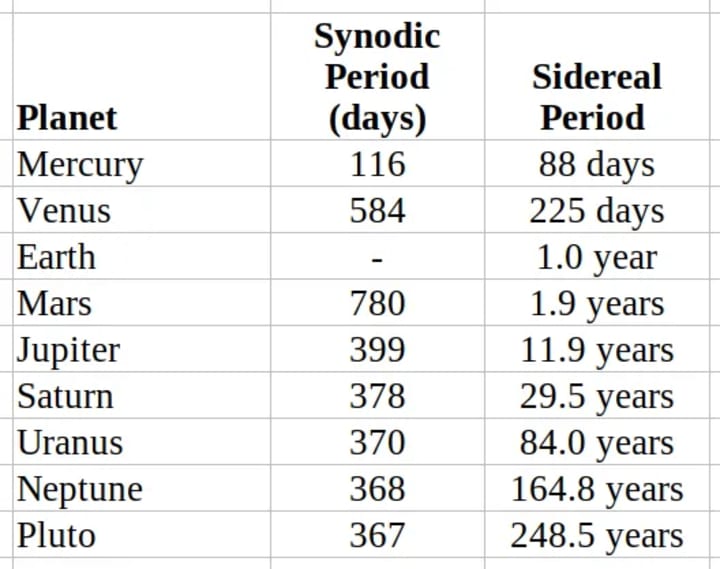

They now believe the calendar represents a 45-year cycle of our neighboring planets and found it linked to synodic periods, which represent the amount of time it takes for another planet to return to the same position in the sky relative to the Earth and Sun. Mercury, for example, has a synodic period of around 116 days; Mars’s is much longer at 780 days.

Prior research attempted to link planetary connections to the 819-day calendar, which is divided into four colour-directional parts. Linden and Bricker note that “its four-part, colour-directional scheme is too short to fit well with the synodic periods of the visible planets.”

They suggest that earlier researchers were too focused with narrow thinking blinding them to the obvious. Some extrapolation and repetition appears to have been the solution staring everyone in the face from the start.

“By increasing the calendar length to 20 periods of 819-days a pattern emerges in which the synodic periods of all the visible planets commensurate with station points in the larger 819-day calendar,” they postulated.

According to NASA,Mercury’s synodic period is 115.88 days. The Mayan astronomers had primitive instruments and estimated the period at 117 days. Pretty good work? That’s nine cycles on the calendar.

The other planets visible from Earth and visible to the Mayans are Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. They all have similar mathematical fits when the calendar is cycled.

Mars, has the longest synodic period at 780 days, which takes 21 periods to fit exactly into 20 cycles, both of which have 16,380 days, almost 45 years.

As I sit here on my boat, with a new moon sharp in the Queensland sky, Venus is a brilliant sight.

And. as they say, there’s nothing new under the moon.

But the Mayans had it figured.

And the Aborigines had the tides figured.

All I need now is more water — the tides are now at neaps and I can’t leave the river yet. And anyway, the wind has been blowing too hard for the last week, and from the wrong direction.

Nothing new there, either!

And cannibalism still takes place.

***

My novels are available at my Gumroad bookstore. Also at Amazon and Apple

Canonical link: This story was originally published in Medium on 29 April 2023

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.