Before Adam: Investigating Ancient Clues of a Possible Pre-Human Predator Lineage

A long-form historical inquiry into early texts, cultural memory, and the disturbing idea that humanity may not have been alone when history began.

From time to time, the oldest layers of human memory reveal things that do not sit comfortably inside our modern frameworks. They appear in fragments, preserved in myths that survived by accident rather than intent, or inside religious texts written long before science attempted to explain the world. What emerges from these fragments is a recurring idea that challenges not only theology and anthropology but the very assumption that humans were the first conscious species to shape life on this planet. There are stories, preserved with surprising consistency, of beings that did not resemble us, did not think as we do, and did not share the same place in the natural order. They belong to a time before recognized civilization, before the agricultural world, before Adam in a theological sense, and before Homo sapiens in a cultural sense.

What makes these stories compelling is their specificity. They do not describe chaotic gods of symbolism, nor the ghosts of moral allegory. They describe creatures with bodies and habits, with behaviors that frightened early communities and left cultural scars deep enough to survive thousands of years. These beings are portrayed as nocturnal, predatory, and physically dominant, and they appear again and again in cultures separated by oceans and entire epochs. The modern reader encounters them as legends of blood drinkers or night demons, but to the people who first documented them, they were not metaphors. They were threats.

One of the earliest sources that preserves a memory of these beings is the Book of Enoch. It is a text that has always existed on the edge of accepted canon, too strange for comfortable theology yet too old to dismiss as invention. In Enoch, the world is populated not only by humans but by entities called the Watchers. The text does not portray them as immaterial forces. They descend, they interact, they reproduce. Their offspring are described in biological terms, towering beings whose appetite for flesh and blood becomes so extreme that even ancient writers, accustomed to mythic exaggeration, seem unsettled.

The striking detail is that the text does not frame their consumption of blood as ritual. It presents it as dietary. They fed in a way that humans would later describe as monstrous, and yet the language is matter-of-fact, as if recording an event rather than inventing a story. When a tradition this old preserves such details, it forces the investigator to consider whether it is preserving a distorted memory rather than a symbolic tale.

The same pattern appears in Mesopotamia, one of the earliest centers of writing. Long before Enoch, the Sumerians spoke of beings called lilû and lilītu. These figures are often reduced in modern summaries to vague spirits, but the original descriptions give them physical attributes that do not resemble the dead. They moved through settlements at night, targeted living humans, avoided daylight, and drained vitality in a way that was clearly understood as predatory. Later Jewish traditions condensed these ideas into the figure of Lilith, but this later spiritual framing often obscures the original presentation. The earliest texts describe her not as a metaphor for chaos but as a physical being with strength, claws, and intentions.

What becomes difficult to dismiss is the global pattern that emerges when these ancient accounts are compared. Cultures separated by vast distances, with no shared language or mythology, describe remarkably similar creatures. In the Andean highlands, Himalayan foothills, the forests of the Balkans, the Sahel, and the islands of the Pacific, there are traditions of night feeders who avoided the sun, lived on the margins of human settlements, and took life in a way that was viewed not as supernatural but as biologically threatening. The descriptions differ in ornamentation, but the essential traits remain constant. Humans do not spontaneously invent the same predator on opposite sides of the world unless they are responding to a shared phenomenon.

This leads to the concept found in some esoteric Judaic traditions of a pre- Adamic world, a period before the human lineage recognized by theology. In these writings, Adam is not described as the first being, only as the beginning of a particular human order. What came before him is left open, but the implication is that Earth may have held other conscious life forms long before agriculture or recognizable civilization. These ideas were never integrated into mainstream doctrine, but they persisted because they expressed something earlier societies considered important enough to preserve. They challenge conventional archaeology, yet they appear in documents created by thinkers who were rigorous in every other aspect of their scholarship.

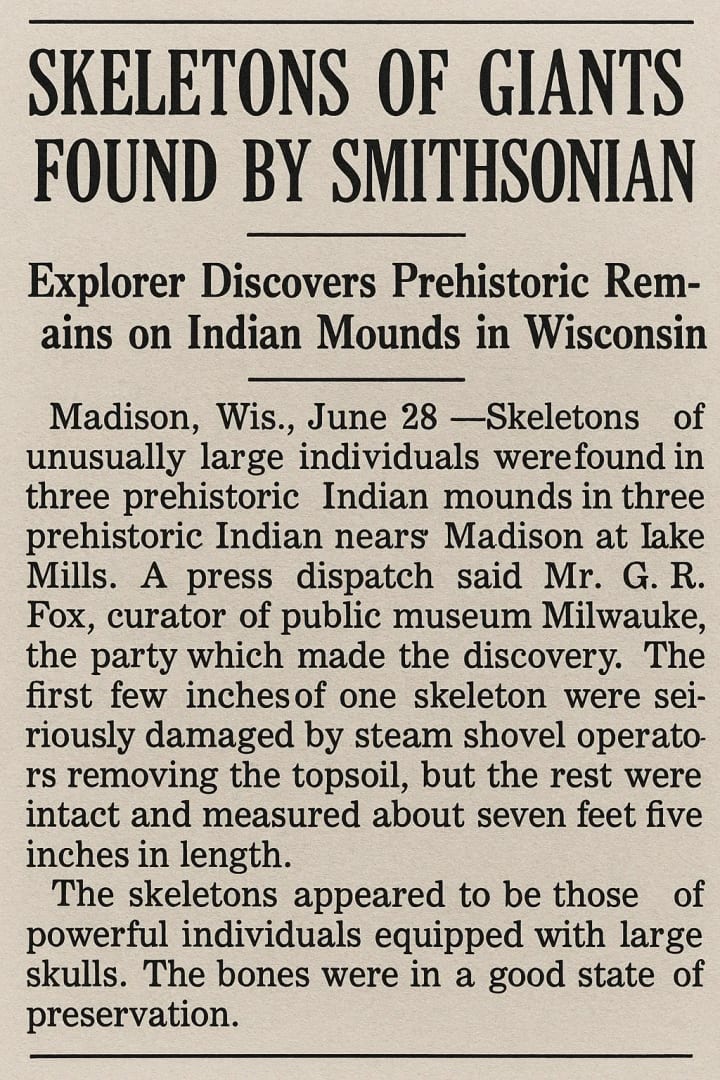

At this point, the modern investigator naturally asks what physical evidence might remain. Here, the trail becomes more ambiguous. Archaeology has not produced a skeleton that can be definitively linked to such a species. However, the absence of evidence is not unusual when dealing with prehistoric populations that may have lived nocturnally, buried their dead in locations now lost, or existed in low numbers. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, reports of unusually large skeletons were frequently announced in newspapers, only to vanish into museum archives or be dismissed under questionable explanations. Whether these bones belonged to an unknown hominid or to extreme individual anomalies cannot be determined, but the repeated disappearance of inconvenient finds is a pattern historians have documented in more than one field.

More compelling than the missing bones are the traces in cultural memory. Across the world, ancient communities established rituals intended not to honor spirits but to repel predators. They used amulets and incantations not against metaphysical forces but against something they believed could physically harm them. This distinction matters. Cultures do not perform material protection rituals against purely symbolic threats. They do so when confronted with something that behaves like a living antagonist.

The inquiry becomes even more complex when the investigation reaches the layer of myth that describes another type of non-human being, one very different from the nocturnal predators yet even older in the mythological record. These are the dragon queens, the reptilian mothers, and the draconic sovereigns. Unlike the night feeders, these beings are not framed as threats lurking in the dark. They appear as rulers.

In Mesopotamia, the earliest known goddess is Tiamat, not as a symbolic serpent but as a literal draconic presence. She commands cosmic authority long before human-shaped gods enter the narrative. She organizes realms, creates offspring, and rules a formative age of the world. Her eventual defeat is portrayed not as victory over chaos but as a political overthrow, the end of a former sovereignty replaced by a new order.

Greek tradition preserves a similar memory in the figure of Dracaena, a serpent woman who governed a northern region and negotiated with heroes not as a monster but as a ruler. Chinese and Southeast Asian myths describe dragon mothers who precede the human dynasties and confer legitimacy upon early kings. These dragon queens are not depicted as symbols. They are depicted as older powers, dethroned but not forgotten.

Taken together, the patterns from these myths create a provocative possibility. Humanity may be remembering not one, but two non-human populations. One predatory and nocturnal, feared and later demonized. The other regal and reptilian, once sovereign and later overthrown. If myths are distorted memories, then humanity’s earliest world may have been shaped by encounters with both a rival species and an older ruling species, each leaving different imprints on the human imagination.

Modern science offers no simple framework for such an idea, yet the consistency of the myths remains. They do not prove that these beings existed, but they show that ancient peoples believed they did, strongly enough to preserve the stories across thousands of years. Humans do not invent predators without cause, and they do not invent rulers with non- human forms unless they are trying to explain something remembered.

This brings us to the most difficult question: why do these stories still matter? They matter because they challenge the assumption that humanity began as the unquestioned apex of life on Earth. They suggest that the earliest humans may have lived alongside others, some dangerous, some dominant, and that our species did not rise in an empty world but in a contested one. If these fragments contain even a shadow of historical truth, then our fear of darkness, our fascination with serpents, and our stories of ancient rulers may all be inherited memories from a time before history.

Humanity may be the inheritor of a world shaped by older hands. And somewhere inside our oldest myths, the traces of those earlier inhabitants remain.

If you found this investigation thought-provoking, consider sharing it with someone who enjoys deep historical analysis. Your likes, shares, and comments help bring these long-form explorations to readers who are searching for serious research beyond the surface stories.

About the Creator

The Secret History Of The World

I have spent the last twenty years studying and learning about ancient history, religion, and mythology. I have a huge interest in this field and the paranormal. I do run a YouTube channel

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.