"A dream of dark and troubling things," is how David Lynch once described his seminal cult midnight movie Eraserhead. He could just as easily have been describing Asparagus (1979), a short film often screened with Eraserhead in the early days.

Stylistically, the bleak, dark, industrial gothic landscape presented in Eraserhead, with its beautiful black-and-white images of desolation and biological distortion and decay, couldn't be further from Asparagus, which is a short (18 minute) blast of kaleiodoscopic psychedelia. Be that as it may, the two films evoke a similarly dream-like world, one involving a protagonist whose identity is one of a variable, shifting, unsettled nature.

The film opens with a young woman squatting over a toilet. Her turds are squeezed out to float in the bowl for a moment before spelling out the title. Before, we've seen a thick woman's leg, like something drawn by Robert Crumb, in a heavy, polished heel. Emerging from a floating circle, a snake begins to twine itself about the leg, futilely hissing out the title of the film, which it can never get quite right. From the start, we have the contrast between male and female energy.

The soundtrack is horn blasts of free jazz with a kind of bee-like hum beneath, but seems to settle into an eerie, ambient drone. This music seems always perched on the edge of expectancy. The images of the house have a shimmering, trembling quality; the colors are warm, soft, muted; easy on the eyes.

A young girl, whose body seems virtually white, whose face is obscured, pulls back a curtain, revealing a landscape of flowers and growth passing mysteriously by. Either her house is in transit, like a train, or the world beyond is this moving garden of beauty. But, perhaps, this is just one of her fantasies?

The illusion of motion stops as two giant legs come down. The image outside the ornate picture windows now is one of several stalks of asparagus growing from the ground. A giant hand reaches down as if to pull these stalks from the earth, but simply strokes them, in a manner that slyly suggests masturbation.

While bundles of beautiful flowers float by the screen, crossing the vision of the viewer with one of unearthly loveliness, we are drawn back inside her home, where a little box-like affair with six spaces is lighted by a flower-like table lamp. Each space seems to be a doll-house reproduction of one of the rooms in the house, including the one where the little box sits on a table, being lit.

One remembers the old saw about a "picture of a man painting a picture, of a man painting a picture," ad infinitum.

It may be a sort of Rorschach test, but many of the furnishings of the home (i.e. a table and a washbasin that seems to be grinning with its tongue lolling from its mouth) suggest faces or bodies; the emphasis on physicality, why the filmmaker chose the visual pun of "asparagus" as the title and thematic undercurrent of the film, becomes apparent.

The girl, faceless, having no identity, is drawn to the asparagus plant, which is phallic in shape and representation, but neuter. The six (sex?) little box-like dollhouses are simulations of her world, little toy representations, signifying nothing real. They are "watered" by the flowery conjurations of her thoughts and dreams, that special "light."

Choosing a womanly face mask from the mantle, she opens up a large clasp bag; brilliant psychedelic lasers and colors, images of cowboys and beautiful starlets, and other free-floating fantasies come swirling inside. She clasps the bag shut. This is her "thought bomb." She's a visionary agent.

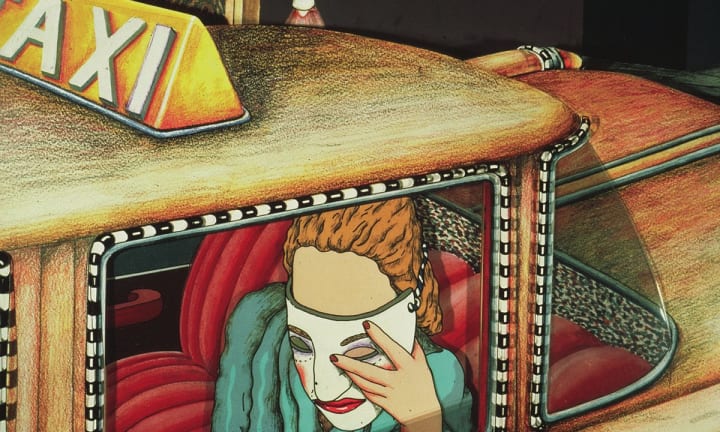

Masked, she takes a cab ride to the opera. Here, we switch animation styles to literal physical puppets, presented as tiny specimens in the audience, at the bottom of the screen. The viewer will appreciate the illusionary double-vision aspect of this, as, for a moment, their mind is fooled into believing they are viewing an event that is real.

As if carrying an explosive device, the masked protagonist of Asparagus enters the opera house. The curtain pulls back to reveal an animated backdrop of a waterfall and fake foam below. The soundtrack becomes two musical patterns, one mewling, squealing horn blasts, and the other, an acoustic guitar riff, competing against each other. The effect becomes annoying, jarring.

The masked girl goes behind the stage backdrop. She opens up her clasp bag, letting her dreams fly out, fly forth like Pandora's demons tormenting the earth. They float above the astounded audience. The waterfall backdrop on the stage has been replaced by a weird, revolving, "dimensional tunnel", honeycombed like a twirling hive with black and white spots. The inscrutable image of an armchair floats above; insects with huge teeth, a toy theater with a tongue, flowers, mollusks; all of these are displayed in surrealistic wonder above the tiny puppet audience. The experimental score turns to random synthesizer strains and weird, crying, sustained notes beneath it all.

Back in the cab, with bizarre, floating visions following her out the door, she once again pulls down her mask, revealing her facelessness, her lack of a formulated sexual identity. At home again, she strips, revealing the swell of her naked breast.

Reaching out the window, she grabs one of the stalks of asparagus growing from the dark earth. She thrusts the phallic stalk of it down her throat, vomiting up a torrent of colors and images: flowers, stars, a ribbon, all suffused with the same flowery yet subdued color of the film. Finally, emerging from her mouth we have a dark, crawling, hairy psuedo pubic bush. And then the thing ends, leaving the viewer as intensely puzzled as they previously were.

A commentator on a short documentary relates that Asparagus creator Suzan Pitt (who crafted the film over several years with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts) chose the title and theme of asparagus to represent a sexuality that was neither fully male, nor fully female. The movie is an "interior voyage"; the girl has no face, no "true self". She is unformed, yet, searching for the reality of her gender, which must walk, hand-in-hand, with her sense of being. But everything is simply as false a reproduction as the mask she wears, the little model rooms she "waters". A flower's beauty fades; yet, it is this beauty she feels as something dreamlike and exterior, something which she wishes to capture in a clasp (vaginal metaphor?), and export in the guise of alternate personhood, a self comprised of identity because infused with the power of her dreams.

The film shimmers to its conclusion; she gives a stalk of asparagus head. But, this is simply another fantasy, another hallucination. In the end, the viewer is left as purely puzzled as they were before.

But they will feel as if they are awakening from a brief, entrancing spell, nonetheless.

Asparagus can be viewed in full at YouTube.

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.