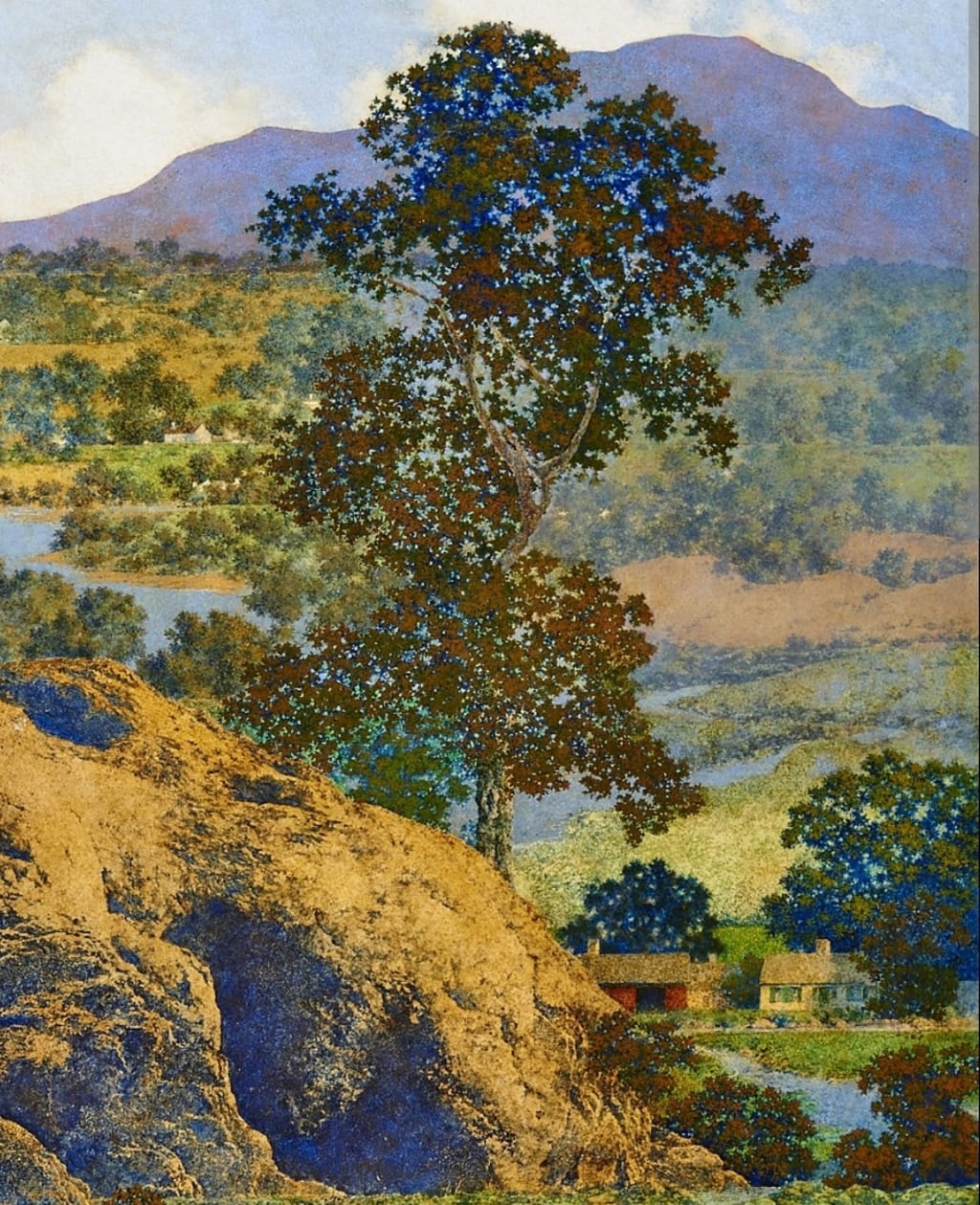

The view from Montcairne Hill is what folks write verses about. I know—I’ve written them. The kind of place where the sky wears its Sunday best and the wind behaves like it was taught manners by somebody’s grandmother. All the fields below look like quilts the Lord laid out for airing—patched in wheat, cotton, and the shimmer of cane.

And yet.

There’s a wrongness tucked in that perfect view. Not enough to name, but just enough to notice if your blood’s ever known trouble. I’ve always believed women carry a sixth sense in the soft of their wrists, just beneath the blue vein—the place where warnings bloom before they speak.

This morning, everything gleamed like a lie polished too well. The kind of morning men marry for and women leave. The sky so spotless it felt like someone had scrubbed it raw. Birds stitched shadows across the porch railing. A pitcher of lemon water sweat in the sun beside me, glass humming like it had secrets to tell but none it could share politely.

Below, the land unfolded just right. That’s what bothered me most.

I sat with my gloves in my lap, not because it was proper, but because my fingers had begun to twitch, and I didn’t want the others to see. Aunt Mercy was napping behind me in the cane chair, mouth open like she was catching ghosts. Cousin Beattie plucked at her embroidery hoop with all the passion of a drowning woman brushing her hair.

And I—I stared down into that perfection with my teeth clenched so tightly I could taste copper behind my molars.

You see, someone once told me Montcairne was built atop a slave graveyard. Not the kind with stones or psalms. The kind they don’t map. The kind you feel when the magnolias won’t bloom on that side of the house no matter how you coax.

They paved the hilltop flat for the parlor lawn, planted St. Augustine grass and built that wraparound veranda like they meant to outlast sin. But nothing ever outlasts sin. It just curls quieter.

I was eleven when I first heard the hum.

Not music—a hum. Low and bone-deep. Like the sound bees might make if they were praying. I heard it again today, the moment the breeze went still. The birds stopped in mid-air, just for half a blink. That’s when I felt it again—the pull, the tilt. Like the world took one breath too many.

And there—by the edge of the tobacco shed—I saw him.

Not a man exactly. More like the shadow of one. Long, lean, all wrong angles. He didn’t move, just watched. Like he was waiting for me to remember something I’d sworn to forget.

My tea glass cracked in my hand.

Aunt Mercy stirred. “Sibyl, child, what are you staring at?”

I didn’t answer. Couldn’t. My voice had gone dry as sermon bread.

She looked where I looked and saw nothing.

Of course she didn’t.

That’s the thing about Montcairne Hill. It’ll show you what you want. What you fear. What you are. But never all at once.

That evening I found a pair of bootprints on the porch. Muddy, though it hadn’t rained in a week. Facing the door. Not away from it.

No one else noticed.

Beattie hummed the same hymn all through supper, though she claimed she didn’t know it. Aunt Mercy’s cane chair rocked itself a while after she went to bed.

And I—I didn’t sleep.

Because the view from Montcairne Hill is perfect. And always has been.

And that’s the part that keeps me awake.

Two nights later, I followed the humming.

I stepped barefoot down the veranda steps, careful not to wake the dogs, the kind of careful a person learns from hiding too many feelings in a corset made for three meals and no grief. The moon was a broken wishbone that night—half hope, half omen.

He was there again.

Standing by the tree where the pines lean wrong. Pines don’t lean, not if they're planted honest. But these bowed like they knew they stood on bones.

He didn’t call me. Didn’t move.

Just waited.

So I went. One step, then the next, until the grass cooled beneath my feet and the air grew still as wallpaper. I stood in front of him, heart beating like it remembered how to run and was trying to remind the rest of me.

He lifted his hand and pointed toward the field. I turned.

And saw them.

Not ghosts. Not quite.

Figures. Shapes. People caught between memory and earth. Their eyes were lanterns. Their hands stained. But they did not burn with vengeance. They burned with knowing.

They watched me the way fire watches wood.

Then the man beside me spoke. His voice was a rustle, a hymn half-swallowed.

"You live where you do not walk. You eat where no prayers have been spoken."

I fell to my knees.

"What do I do?" I whispered.

He leaned close. His breath was orange blossom and blood.

"Remember us right."

And then he was gone. As if he’d stepped backward into the hush.

The grove quieted.

The next morning, the pine nearest the shed split in two. No lightning. No wind.

Inside the trunk: bones.

Small. Many.

Now the view from Montcairne Hill has changed.

Not worse. Not better.

But true.

About the Creator

Taylor Ward

From a small town, I find joy and grace in my trauma and difficulties. My life, shaped by loss and adversity, fuels my creativity. Each piece written over period in my life, one unlike the last. These words sometimes my only emotion.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.