Bimpe was nervous.

Her stepmother, Doyinsola, had charged her with presenting the family’s annual offering to the shrine of Mami Sonu-Mesan. Bimpe had even been given fresh clothes for a change – a pretty red gele, a spotless white iro, and a red-and-white striped buba. A part of her was overjoyed to finally leave her compound after years of near-imprisonment.

But, she was also nervous.

Doyinsola never spent any of her cowries on Bimpe. New clothes and public honors were reserved for her daughters, Ayotola and Eniola; mis-matched rags and beatings were reserved for Bimpe. This had just been the way of things ever since Bimpe’s father Oyediran, oba of the village and babalawo of Orunmila, had left one day to see the Shango in Ajaka and never returned.

So it was that Bimpe found herself standing before the inlet in the banks of the Forgotten River that served as Mami Sonu-Mesan’s shrine, wondering what she should do.

Why did stepmother forbid me from looking in the bag? Bimpe wondered to herself, looking down at the costly beaded bag that contained her family’s offering. This has to be a trick.

She wouldn’t dare try to trick Mami Sonu-Mesan – no one would, she argued with herself.

She might, if she thought I’d get the blame. She told the elders ‘I’ broke Baba’s shrine - MY ancestral shrine - when it was really Eniola! When I told her that Ayotola was eating the offerings I left for my ancestors, she beat me for lying! The memory of those injustices still made her hot with anger. If she doesn’t care about my ancestors, why would she care about Mami Sonu-Mesan?

Bimpe looked up from the beaded bag, her eyes drawn to the nine wooden carvings of Mami Sonu-Mesan that surrounded the inlet. Many of them had snake skins tied around their waist. All of them had been adorned with strips of red and white cloth that fluttered in the warm morning breeze.

Red and white: Colors for death and life, Bimpe reminded herself. Nine carvings for her nine children, who drink the blood of bad children.

She shivered and clutched the doll that lay hidden against her chest. It was a doll stuffed with rags and the few shards of bone and wood she’d been able to salvage from her father’s shrine. Her ancestors lived inside the doll and sometimes, when she was able to sneak them a good offering, it was able to help her with her chores.

“What should I do?” she asked her ancestors.

“Give the offering,” the little doll whispered. “Trust in the gods.”

Bimpe sighed, but nodded. She waded into the center of the inlet and dropped the beaded bag into the water. It bobbed and glittered in the sunlight as the water’s gentle current carried it out of the inlet into the river.

Suddenly, a furry hand reached out of the river and snatched the offering. Bimpe blinked with surprise, then gasped as a massive snake entered the inlet and surrounded her with its bulk.

No, not a snake, she realized, her knees wobbling with terror. Snakes don’t have fur, or legs, or a hand on the end of their tail. It’s the water dog; it’s Mami Sonu-Mesan’s familiar! It has to be!

The creature lifted his head and forelimbs out of the water. As he opened the offering bag with his dexterous hands, Bimpe noticed that his wet fur was standing on end in little tufts, rather than lying flat like it should have.

“Definitely a water dog!” Bimpe cried out loud.

The water dog looked up from the contents of the bag and glared at Bimpe.

I knew it! I knew stepmother was tricking me! she thought to herself, both furious and terrified.

Bimpe’s knees finally gave way, and she sank down into the water up to her neck.

“Please, water dog, please! I was forbidden to look in the bag. It’s…the offering is from my stepmother and stepsisters, not from me!”

The water dog stared at Bimpe for a long moment, considering her with his intelligent gaze. He then passed the offensive offering to his tail-hand, grabbed Bimpe by the shoulders, and pulled her under the river with him.

Bimpe closed her eyes and yelled with fright – convinced that the water dog meant to drown her – only to realize that she could now breathe underwater. Somewhat reassured, Bimpe opened her eyes. She expected the river to be murky and dark, but instead found that she could see as clearly as a fish.

The water dog was taking Bimpe through a dense forest of hippo grass and sorghum, his long body and powerful tail propelling them swiftly through the cool water. Deeper and deeper they went – much deeper than Bimpe had ever imagined the Forgotten River could be – and still the riverbed was nowhere to be seen. The sorghum now grew taller and wider than any tree Bimpe had seen, and the catfish browsing below were the size of hippos.

A pair of gap-toothed, beautiful mermaids watched with interest as they passed.

“Ooh, she’s a pretty one. I wonder what Mami Sonu-Mesan wants with her?” the first jengu asked the second, her magical voice carrying through the water.

“Perhaps she’s been good, perhaps she’s been bad; either way, it is not for us to interfere, sister,” the second jengu replied.

“It would be a waste of beauty if she was fed to Mami Sonu-Mesan’s children,” the first jengu sighed.

“I’ve been good, I swear!” Bimpe tried to tell them, twisting around in the water dog’s grip, but the river swallowed her words.

The water dog growled at her, his meaning clear: Keep quiet.

Frightened again, Bimpe stopped struggling and faced forward. She then noticed that the water dog was swimming down toward a strange, pulsing light hidden within the hippo grass. A few seconds passed, and Bimpe realized that not only were they moving toward the light, but the light was also moving toward them.

Slowly, a turtle the size of a small island emerged from the hippo grass. Bimpe barely noticed the meadows of flowing lichen clinging to the turtle’s shell, or the powerful movements of its clawed flippers: She was too busy staring at the gap in the turtle’s shell where its head should have been – empty, but for an odd, flickering light.

With a flurry of movement from the water dog’s powerful tail, they entered the turtle’s shell. Suddenly, Bimpe was no longer underwater, breathing water; she was breathing air and being carried across a tranquil pond to a small jetty. The jetty was attached to a small island with a single hill. On top of the hill sprawled a wide house with many windows, a high conical roof of thatched reeds, and a heavy curtain draped across its entryway. The path up the hill from the jetty was littered with fish bones and lit by crocodile skulls hanging from poles – skulls whose eye sockets flickered with the same unnatural sunlight that filled the house’s windows.

Bimpe’s jaw went slack with awe and wonder, but she quickly sputtered and coughed as some water sloshed into her gaping mouth. Still coughing, she fell over flat when the water dog finally dropped her unceremoniously onto the jetty. By the time she got to her feet, the water dog was waiting at the other end of the pier, beckoning her impatiently with his tail-hand. When she spied her offering bag glittering in his mouth, the fear began creeping back into her mind. She jogged along the jetty as best she could in her iro, but she couldn’t move very fast without stumbling or tripping.

When she finally reached the end of the dock, the water dog grabbed Bimpe’s wrist with his tail-hand, and dragged her up the path and into the lantern light. As she was led up the hill, stumbling in the eerie half-light, her mind was swimming with all the tales she’d been told about Mami Sonu-Mesan and her children.

“Omobolanle said that Erioluwa saw one of her children drinking the blood of his baby nephew,” Bimpe said, talking aloud mostly to herself, but maybe to the water dog too. “But, when he told people about it, a vulture flew over his house and his tongue shriveled in his mouth.”

Bimpe glanced to her left, past the lanterns, and saw a large garden of strange plants.

“My ancestors once told me that there was a man, Bamidele, who wronged Mami Sonu-Mesan. He read about Mami’s lesser cousins, the soucouyants, and learned that they could be distracted and delayed by scattering seeds on the ground, which they must pick up one at a time. He thought he was clever, and could evade Mami the same way. Mami Sonu-Mesan, however, just had hundreds of her skeletal hands pick up the seeds for her.”

As she spoke, a dozen such skeletal hands crawled through Mami Sonu-Mesan’s garden like rickety little spiders. They planted seeds, harvested berries and pruned the dead branches off of a few twisted bushes. Seized by morbid curiosity, she watched the hands work and dragged her feet against the water dog’s tugging.

“Hey–” she was about to ask the water dog where Mami Sonu-Mesan had gotten all the hands from, when she felt her ancestral doll beating its little cloth fists against her chest.

“Don’t ask about the hands!” The doll warned and pleaded with her in its little whispering voice.

Bimpe heeded the advice of her ancestors and kept quiet.

It was then that the curtain into Mami Sonu-Mesan’s abode was thrown aside and more light cascaded down the hill.

“Hurry up and get in here before I have Onirunokun drag you by the scruff of your neck!” a woman’s nasal voice snapped.

Bimpe jumped, hiked up her iro, and began jogging up the hill. Fish bones crunched underfoot and scattered before her toes. The water dog no longer dragged her – fear or magic was propelling her legs forward without his help. In no time at all, Bimpe was passing beneath the two elephant tusks that stood lashed together over the entrance to Sonu-Mesan’s home.

Mami Sonu-Mesan’s circular living room was lit by a single fire burning in a central pit – a fire which cast far more light than its feebly flickering flames should have. The high thatched roof was festooned with trinkets and baubles. Fetishes of such great power that even Bimpe could sense their strength dangled side by side with mere curiosities. Ten large stone basins stood at even intervals against the walls, with the occasional bookshelf, window, or curtain-covered doorway filling the space between them. Mami Sonu-Mesan came tottering into the room through one such doorway.

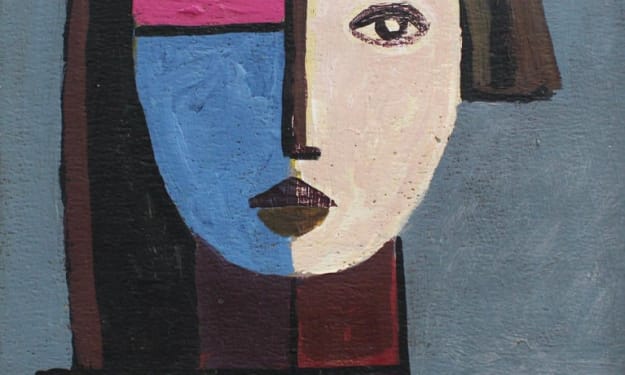

Mami Sonu-Mesan appeared to be a blind, wizened, old woman with ebony skin. Her white dreadlocks, decorated with rings and cowrie shells, were so long that they nearly touched the ground as she hobbled along with the aid of her ornately carved staff. She looked harmless enough, but Bimpe – young though she was – knew better than that.

Bimpe knew that Sonu-Mesan’s children had once tried to steal her staff, but they had been unable to lift it from the ground – even when all nine of them lifted at the same time. However strong Mami Sonu-Mesan was physically, Bimpe knew her magic was much stronger. She could turn Bimpe into a turtle with a flick of her wrist.

A wooden stool scuttled out from behind one of the stone basins and positioned itself in front of the fire. When Mami Sonu-Mesan lowered herself onto the stool with an ill-tempered grunt, Bimpe hastened to prostrate herself at the river goddess’ feet.

“About bloody time,” Sonu-Mesan grumbled.

“I-I’m sorry, Mami. I just…wanted to look at your garden.”

“I didn’t bring you here to gawk at my flowers and appraise my vegetables!” Sonu-Mesan snapped as Onirunokun dropped the offering bag in her lap. “I brought you here to explain yourself.”

Bimpe held her breath as Sonu-Mesan reached into the beaded bag and withdrew a severed head. It wasn’t just any severed head, however: the hair Sonu-Mesan was clutching in her fingers was silver, and the head itself seemed to have been carved from a single giant pearl. The head was no larger than that of a toddler.

“Do you know what this is?” Sonu-Mesan asked, waving the grotesque offering in front of Bimpe.

“I-It’s a yumboe’s head,” Bimpe replied, horrified and sad and angry all over again. “My stepmother she…she set out a trap for him. Said she was tired of them stealing our food.” She brushed aside a few angry tears. “I told her we had plenty of food, and that yumboes bring good luck. She beat me and said she didn’t care!” She sniffed and bowed her head until her nose touched the floor. “I’m sorry, I should have guessed…should have known what the offering might be.”

“Did you tell your stepmother that the yumboes of this river are my subjects?”

“I tried–”

“Talk to me, not the floor,” Sonu-Mesan demanded testily.

Bimpe jerked upright to look Mami Sonu-Mesan in the eyes.

“I tried to tell her, but she wouldn’t listen to me. She never does.”

Sonu-Mesan sucked on her gums as Onirunokun curled around the legs of her stool, watching Bimpe unblinkingly.

“So, this is the offering of your stepmother and stepsisters. Fine,” she turned her head and spat on the ground. “What is your offering then?”

Bimpe blinked. She had, of course, brought nothing else aside from herself.

“You, who live on the banks of my river, brought me the offerings of others, but did not think to offer anything of your own as thanks for the protection I provide? Are you not the daughter of a priest and priestess? Did they teach you nothing before they became one with their gods in death?” Sonu-Mesan jabbed Bimpe’s chest – exactly where her doll was hidden – hard enough to knock her onto her back. “Has being trapped in that doll so dulled your ancestors’ wits that they didn’t think to tell you to bring me something?”

“I-I could clean for you!” Bimpe offered desperately.

Sonu-Mesan rubbed her wrinkled cheeks and grumbled to herself.

“Alright, alright,” she eventually said, snorting and spitting to her right. “I need to gather materials for your stepfamily’s reward. Clean this place top to bottom, crack and corner, by nightfall and I’ll forgive your slight.”

Bimpe didn’t understand why, in the name of all the gods and goddesses of Midaye, Sonu-Mesan would reward her stepfamily. Nevertheless, she knew better than to question the ill-tempered goddess.

“I’ll do my best,” Bimpe promised.

Mami Sonu-Mesan snorted as she got to her feet.

“I know, girl, now get to it,” she commanded as she hobbled outside with Onirunokun following at her heels.

Bimpe carefully hiked up and knotted her iro above her knees, rolled up the sleeves of her buba, quickly located the nearest clean rag, and got to work. First she went around dusting all of the bookshelves, while her doll used some of its modest magic to help clean the various trinkets and treasures hanging from the roof. The floors were covered in Sonu-Mesan’s phlegm and spit so she scrubbed the floor with water drawn from the island’s edge.

Bimpe was almost done cleaning the floor when she heard her doll’s little voice gasp.

“Orunmila’s eyes!”

“What is it?” Bimpe asked nervously as she looked up and searched for the doll.

It didn’t take her long to locate both the doll and the source of its exclamation. A fly whisk hung from the ceiling by a simple leather thong. Its hairs were old and faded, but its handle was made from solid, many-faceted, glittering adamantine.

“Ọsanyin’s herbs!” Bimpe breathed. “It’s beautiful. I wonder where it came from.”

“We don’t know. No oba wealthy and pious enough to make an offering of pure adamantine has visited our village in all our memories.” The doll paused, then shook its little rag head. “We don’t have time to be distracted. There is much work still to be done.”

Bimpe nodded and reluctantly moved on to clean Sonu-Mesan’s side rooms. One side room was a cramped closet filled with skeletal hands, which she dutifully dusted and cleaned. She considered organizing the hands by size, but quickly decided against it – after all, Sonu-Mesan probably had her reasons for arranging them as they were. Another room was filled with a bewildering array of pots, spoons, and knives. Fortunately, most of these cooking tools were quite well-maintained, and only a few of the more recently used knives and spoons needed cleaning.

Bimpe’s doll scampered off while she was cleaning the last of Sonu-Mesan’s knives – an extremely thin, sharp one that she’d nearly cut herself on three times.

Cleaning isn’t so bad when someone isn’t hovering behind me, yelling at me to work faster, she reflected almost cheerfully.

Her doll returned when she was hanging the knife up on its hook.

“Skip the last room, the stone bowls need cleaning,” the doll insisted.

“What, really? What’s in there?” Bimpe asked, returning to the living room and glancing at the third doorway.

“Trust us, and do as we say. What lies behind those curtains is not for the eyes of children.”

“I’m not a child!” she protested.

“We do not have time to argue. Look out the windows – what little light reaches this enchanted island dims. The bowls will take some time to clean, even if we help.”

“Okay, okay,” Bimpe relented, walking up to the first stone basin.

It was taller than she was.

“How are we going to clean these?” she asked.

“We’ll clean the inside, you can clean the outside. Drop us in, and we’ll climb out when we’re done.”

That made sense to Bimpe. So, she stood on the tips of her toes, dropped the doll into the basin, and set to work. The sides of each basin were as smooth as river pebbles, save where symbols of power had been carved into the stone. It was in the deepest grooves of these carvings that grime and dust had gathered, so it was there that she scrubbed the hardest.

“Baba told me once that Mami Sonu-Mesan’s children leave their legs and hips behind in these bowls when they go out hunting. Does that leave a mess behind?” Bimpe asked the doll.

“Surprisingly, no,” came the doll’s whispered reply. “At least, not the sort of mess you’d expect – no blood or guts – just some dirt and mud from their feet, we think.”

“Odd,” Bimpe said.

The strange half-light that had fitfully illuminated the interior of the turtle shell was gone by the time Bimpe finished scrubbing the last bowl’s symbols. Bimpe was dabbing the sweat from her brow with the last clean part of her rag when she heard the slow crunching footsteps and wooden tap-tapping of Sonu-Mesan’s return. Bimpe hurriedly stuffed the doll back down the front of her buba and went to stand by the fire.

Onirunokun crawled through the entry first, followed closely by Sonu-Mesan. Mami Sonu-Mesan was carrying a brand new crocodile skull lantern. Bimpe noticed that – unlike the others hanging from their posts outside – this lantern had been given a third eye socket, and that a large glittering diamond had been placed in each one. A sun-in-turtle symbol had been etched into the skull’s snout, surrounded by the symbols for a dead mother and a living woman.

Onirunokun scurried around the house, inspecting Bimpe’s work with little grumbles and growls, while Sonu-Mesan tottered over to her stool and sat with a loud grunt. Bimpe held her breath when Onirunokun slipped through the curtains of the last room – the one she had not cleaned – then let it out when his return did not elicit any comment from Sonu-Mesan. It was only after Onirunokun had finished inspecting each of the stone bowls that Mami Sonu-Mesan spoke.

“You’ve done well, child, you and your doll both,” Sonu-Mesan said.

Bimpe stared for a moment – she had been expecting anger, insults, and demands to do everything over again – then prostrated herself.

“Thank you, Mami,” she replied – mindful this time to lift her head when she spoke.

“I have completed your stepfamily’s reward for their offering,” Sonu-Mesan cackled nastily. “You may ask me two questions before I send you on your way to deliver it.”

Bimpe eyed the new lantern, suspecting now that Sonu-Mesan’s ‘reward’ would be a harsh lesson for its intended recipients, before turning her gaze to the forbidden curtains.

“Mami Sonu-Mesan, what is in that room?” She pointed, and the water dog’s eyes followed her gesture. “My ancestors told me that it was clean already, and that I shouldn’t go in.”

“And you think yourself wiser than your ancestors? You would know what they would keep from you?” Sonu-Mesan asked sharply.

“Well, I mean…” Bimpe frowned and fiddled with her knotted-up iro, “...the ancestors told me not to look. I’m not asking to look, I’m asking to know. Maybe I’ll tell others and one day, some other girl or boy will be here, wondering what’s in there. If they don’t have ancestors to look for them and warn them, maybe the stories I tell will have warned them instead?”

Sonu-Mesan squinted at Bimpe with her milky, blind eyes. The old fey goddess’ withered lips slowly twisted up into a smirk.

“Alright, clever little bird…let’s find out how much you like being clever when you hear what it has bought you. That room is where the human skins I have gathered hang to dry, and it is where I keep the blood my children have gathered. The skins I send to my lesser soucouyant kin to wear as disguises during the day. The blood I give as offerings to the cipactlians of the deep earth and sea, and the adze of the sun.” She reached out to lightly prod one of Bimpe’s cheeks. “Do you know why Mami Sonu-Mesan does these things?”

“To protect us?” Bimpe answered uncertainly.

“To protect you, and all the villages on my river,” Sonu-Mesan confirmed. “The skins which the soucouyants buy from me all bear my mark – a mark that empowers them, but which also lets me know where they are. This discourages them from preying on my people. My blood offerings satisfy most cipactlians and adze, and keeps them from devouring or possessing people like you. My children hunt those who are not satisfied.”

“You’re like an iyalode watching and negotiating with her neighbors,” Bimpe said with a slow nod.

Bimpe knew that she had one more question to ask. For a brief moment she considered asking where and who the skins came from, but a quick, fearful glance at the curtain of the third room made her think better of it. She knew she had to think of a second question before Sonu-Mesan grew impatient, which was bound to happen soon.

“Mami Sonu-Mesan, where did you get that adamantine fly whisk?” Bimpe asked.

Onirunokun glanced up at the whisk, and Sonu-Mesan uttered a small chuckle.

“I got it from this river, and from my mother – whose name was forgotten for a thousand years. It was the hilt of her sword, but it was broken in a great battle.”

“Broken?” Bimpe gasped. “I thought nothing could break adamantine!”

“Yes broken, do you see an adamantine sword hanging from my roof?” Sonu-Mesan asked testily.

“But how–”

“I gave you leave to ask two questions, not three,” Sonu-Mesan interrupted with a scowl.

Bimpe wisely closed her mouth and pressed her forehead to the floor. When she looked up again, Sonu-Mesan thrust the new skull-lantern into her hands.

“Take this to your step-mother’s house. When your step-mother and step-sisters have received their due reward, follow the lantern’s instructions exactly. Do you understand?”

Bimpe got to her feet and hefted the heavy lantern by its bone handle.

“Yes, Mami Sonu-Mesan,” she replied dutifully.

Sonu-Mesan grunted doubtfully.

“We’ll see. Now close your eyes and turn around in a circle three times.”

Bimpe was confused, but nonetheless did what she was told. When she had spun three times and was properly dizzy, she felt Sonu-Mesan’s gnarled fingers take hold of her shoulders. Bimpe was lifted off her feet like she weighed nothing at all, given a final half-turn, and placed back on her feet.

“Now walk forward and don’t open your eyes until you pass through my curtain,” Sonu-Mesan commanded.

As Bimpe walked forward she felt the floor shifting beneath her feet, as though the wooden planks were suddenly made of mud or sand. She took nine steps before she felt the soft cloth of Sonu-Mesan’s front curtain against her face. Bimpe took another step, through the curtain, and opened her eyes.

Bimpe’s mouth fell open. She was back on the riverbank, staring at the inlet with Mami Sonu-Mesan’s nine wooden carvings. The moon rising in place of the sun and the heavy bone lantern in her hands were all that marked the time she had spent in Sonu-Mesan’s abode.

Seized by the sudden, somewhat irrational fear that Onirunokun would emerge from the river and bite at her heels if she dawdled, she hurried up the riverbank and dashed across her village. She met no-one on her way home – everyone was inside making dinner or telling stories in their compound courtyards. So it was with Bimpe’s step-family, who had gathered in her father’s grand courtyard to discuss Bimpe’s fate. Bimpe hid in the shadows of the doorway and listened.

“Can’t we wait until morning to tell everyone that Bimpe is missing?” Eniola complained. “It’s late, and I’m hungry!”

“That’s precisely why we cannot wait, ọmọ mi,” Doyinsola replied, ever patient and gentle with her daughters. “A child who doesn’t return home to eat is a child that is in peril, and who needs to be found. We must continue pretending to be concerned – at least for a time.”

“Why?” Ayotola asked.

“Because,” Doyinsola said through gritted teeth, “her father was much loved here, and if we are suspected of having a hand in the girl’s demise, we will be turned out of this compound as quick as a snake can strike. I’ve spent months and months keeping the girl confined here, while telling people that her father’s death has permanently turned her mind. Showing the elders her father’s broken shrine, hinting that she hurts herself, feigning a mother’s bleeding heart; all while rejecting help from the local priestesses for fear of ‘bringing shame upon my husband’s memory’ – it has been a carefully crafted act. This act was necessary if you two were to inherit anything save what scraps Bimpe chose to allow you, and it will continue to be necessary until the village loses all hope of her recovery.”

“Which will come when the priestesses ask Mami Sonu-Mesan for aid, and she tells them about her offering,” Ayotola laughed.

“Further proof of her tragic madness, yes,” Doyinsola confirmed.

Bimpe stepped out of the shadows and entered the moon-lit courtyard. Ayotola and Eniola just stared. Surprise stole across Doyinsola’s face, followed swiftly by selfish fury.

“BIMPE!” She barked as she stormed over. “Where is the beaded bag I gave you!? What have you done to the clothes I bought for you!? What is that thing you’re carrying!? Answer me!” She demanded without giving her time to do so, seemingly just to give herself an excuse to slap Bimpe.

“The bag was taken, along with your offering, by Mami Sonu-Mesan,” Bimpe replied quietly. “My clothes were dirtied cleaning her home, and this lantern I carry is Mami Sonu-Mesan’s…reward, for your offering.”

If Doyinsola sensed any warning in Bimpe’s hesitation, it did not stop her from snatching the lantern out of her step-daughter’s hands. Part of Bimpe wanted to close her eyes when Doyinsola lifted the lantern up to inspect its jewels, but the larger part of her felt compelled to watch.

It happened in an instant.

Beams of vengeful sunlight arced outward from each of the three stones set in the crocodile’s skull, and entered the bodies of Doyinsola, Ayotola, and Eniola through their mouths and eyes. Their eyes, tongues, and everything inside of their bodies crumbled into ash – ashes which were scattered when their skins fell to the ground like empty bags.

Horrified, Bimpe stared at the skull-lantern where it lay in the dirt, its three jewel eyes flickering with a faint, greenish-blue light. She wanted to run. Where? She didn’t know, just far away from those empty skins and that horrible lantern. She didn’t run. Mami Sonu-Mesan had said that the lantern would have instructions.

So, she waited.

She didn’t have to wait long.

“Pick me up,” the lantern commanded, its bones and teeth clacking together as it spoke with the voices of all three souls trapped inside.

Bimpe hastened to obey, terrified that the lantern might take her soul next if she didn’t. The lantern seemed heavier somehow, though Bimpe knew that souls didn’t actually weigh anything. She held it out at arms length.

“Carry me to the nearest crossroads,” the lantern ordered.

Bimpe ran through the village as fast as her legs would carry her. Nearly all of the village dogs ran after her, gamboling around her feet and nipping playfully at her heels.

“They are a good omen,” her doll reassured her.

She nearly tripped over the dogs three times on the way to the crossroads, but she was too scared to be angry with dogs for being dogs.

Half an hour later, she finally reached the juncture of three dirt roads.

“Stand in the middle of the crossroads and wait,” the skull-lantern told her.

“F-For how long?” Bimpe asked.

The lantern didn’t answer.

So, Bimpe crouched down in the middle of the crossroads and waited.

“At least I have company,” she reflected, watching the pack of excited dogs roll in the dirt, and dash through the long grass.

She was scritching one of the dogs behind his pointed ears when suddenly the entire pack began howling. She heard footsteps behind her, but before she could turn around she was knocked over onto her back by the dogs as they ran to greet whomever those footsteps belonged to.

An old man wearing a wide-brimmed straw hat leaned down and offered Bimpe his hand.

“Up you get, girl,” he said. His voice was deep, smooth, and reassuring. “That’s it.”

Bimpe got to her feet with the old man’s help. She paused briefly to brush the dust and road dirt from her once-clean iro before straightening up to get a look at the aged wanderer. His beard was scraggly, and his dashiki was plain and travel-stained. She might have thought him a poor hermit if not for the dogs’ behavior, his smoking pipe, and his staff. The bowl of his pipe was beautifully carved in the shape of a spider with a woman’s head, and the smoke that rose from it twisted around into fanciful shapes. His staff was unremarkable at first glance – plain gray wood with a head that was shaped like a dog’s – but the wood seemed to change color and texture each time Bimpe blinked. When Bimpe noticed this and tried staring at the staff, its head caught her eye and winked at her.

Any child who knew anything knew to whom that staff and that pipe belonged.

“Papa Legba,” Bimpe gasped.

She wasn’t sure whether to fall to her knees again or remain standing, so her knees compromised by wobbling uncontrollably.

“Am I?” he replied with an amicable laugh, before extending his hand once again. “Now, let me see what you have there.”

Bimpe handed over the lantern, and watched as Papa Legba stared deep into its three gemling eyes. At length, he uttered a small sigh.

“Of course,” the old god muttered to himself. “Sonu-Mesan nurses a special sort of anger for those who mistreat children.”

Papa Legba then lifted the lantern and held it out toward the head of his staff, as though offering an animal a choice morsel. Bimpe jumped when the wooden dog head opened its fanged maw, lunged forward, and swallowed Sonu-Mesan’s lantern whole.

“Wh-What will happen to them, Papa Legba?” Bimpe asked quietly, staring at the now quiescent staff.

“Their lives may be over, but they have lessons they need to learn before I take them to their ancestral shrine in Ajaka.”

Papa Legba sat down with a grunt, laid his staff across his lap, and reached out to pet the dogs sniffing at his clothes.

“Now, you are at a crossroads both figuratively and literally,” he told Bimpe, tossing her a wink. “You can choose to run along back to your village, back to your compound. With the help of Sonu-Mesan’s priestesses, you can probably explain what has happened to your…well, your family for lack of a better word. Or, you can come with me, and I will take you to the home of your uncle in Babashehir.”

“Aburo Adenrele?” Bimpe shuffled her feet.

She knew that her mother’s brother had traveled far away to Babashehir when she was very young, but she knew nothing else about him.

What if my aburo is just as bad as my stepmother? What if he’s worse? she fretted.

Impossible, she told herself. Besides, I have the chance to travel with the god of travel and stories and…and tricks.

“Why…are you offering to take me to my aburo, Papa Legba?” she asked warily.

Papa Legba gave her a wide, crinkling smile.

“Because you’re a good girl who honors her ancestors, listens to the gods, and does her best. You don’t deserve to be cooped up like a chicken, you deserve to see the world.” He stood up and offered Bimpe his hand.

It's an empty compound and a village that believed Doyinsola’s lies, or traveling with Papa Legba and meeting my aburo, Bimpe told herself.

Bimpe clutched her doll in one hand, and took Papa Legba’s hand with the other.

*************************ABOUT MIDAYE***************************

This story is set in a fictional realm of my own devising: Midaye. This world draws inspiration primarily from the religions, folklore, culture, and history of Sub-Saharan Africa; along with those of pre-colonial Mesoamerica, Mycenean Greece, the Indian subcontinent, and Mesopotamia.

************************AUTHOR'S NOTES**************************

On the Inspiration:

- This short story is a loose adaptation of the classic Russian folktale: Vasilisa the Beautiful.

On Regionality:

- The Offering takes place in a part of Midaye analogous to the Medieval Yoruba kingdom known as the Oyo Empire. This is why most of the names and clothing are Yoruba in origin.

- The Forgotten River is one of several major rivers that split off from the Tlaxcala. The Tlaxcala analogous to the Amazon, and serves to connect - albeit distantly - the immediate surroundings of this story with Mesoamerican-inspired lands.

On Names:

- Bimpe is a Yoruba name which literally means: one who is gorgeous or beautiful. I chose this name as a nod to the Russian heroine's epithet.

- Mami Sonu-Mesan's name is significant for two reasons. The honorific 'Mami', coupled with several details surrounding her devotional statues and her dominion over the river, is meant to evoke the title of Mami Wata - a class of Yoruba river deity easily syncretized with the miengu (pl. of jengu) of Cameroon Bimpe encounters on the way to her underwater home. Sonu-Mesan roughly translates to 'Lost Nine' in Yoruba, a name which - taken together with the unusual fly whisk she keeps and her status as a river goddess - serves to connect her with the Yoruba goddess, Ọya. This connection is explored further in other works.

On Creatures:

- Adze are creatures of Ghanian folklore, most often depicted as blood-drinking fireflies that can both transform into and possess humans. While adze are most often associated with evil witchcraft, there are other accounts that hold adze to be neutral sources of power - nothing more or less. In the world of Midaye, adze are a diverse class of blood-and-light associated aberrations that predate the world - the vast majority of which are trapped in the sun through the combined efforts of the solar deities.

- Cipactlians are the spawn of Cipactli - the primordial monster the Aztec gods were purported to have subdued in order to shape the world. Midaye was shaped in a similar manner, with the elven gods subduing the creature and shaping its still-living body into the world.

- Soucouyants are blood-drinking hags out of Caribbean folklore. They are known to leave their skin behind in a stone mortar in order to fly through the night as a fireball, but - like many vampiric creatures - they are also known for fits of compulsive counting. Given their association with night-time light and consuming blood, Midayean soucouyants are classified as adze-infused fey.

- 'Water Dog' is an English translation of the Nahuatl term: ahuizotl. In Mesoamerican folklore, ahuizotl are known for being the servants of water gods. In Midaye, ahuizotl are similarly found in the service of river deities and as servants granted to their highest priests.

About the Creator

T. A. Bres

A writer and aspiring author hoping to build an audience by filling this page with short stories, video game reviews/rants, history infodumps, and comparative mythology conspiracy theories.

Come find me @tabrescia.bsky.social

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.