There had not always been dragons in the valley. But that was because most people did not understand what dragons were. As I staggered through the noisy camp I wondered whether Karrigan had understood the truth. It was doubtful, because if he did know, then this whole affair of poisoning me made him a colossal fool.

For what felt like the seventh time, I had to pause my purposeful march to vomit at the wayside. When the tears cleared from my vision I saw the three figures heaped nearby. Foam poured from their mouths, eyes webbed by red veins. He had killed the servants too. That was crafty: trapping me here until exposure did the deed that crushed seeds could not. Were I as heartless as him, I would have applauded his cunning.

I lurched away from the bundle of corpses – no time to wallow in guilt. I pushed myself to continue my plodding steps. There was no time to wait for the soldiers to overcome the poison’s effects and I would be only a hindrance to the healer women and their noble art. They had to save those who were more harshly dosed. I had a few minutes until I was in lethal danger, and had a far more pressing task to tend to if I planned to avert further loss of life. My task was to find Karrigan – to stop him if I could. How, I did not know, but I was the only one with a hope.

Walking grew progressively more painful as I pushed myself to leave the camp. The path to the ruin was longer than I could recall it being on any of the previous visits during our stay. I fell a great many times, but dragged myself upright each time and staggered onwards. When I reached the edge of the cliff which the ruin was carved into, I threw a glance down into the gorge and was again struck with awe at the enormous complex in the rock face. As I scurried down the uneven ramp to the deepest level, I realised with a sinking gut that the great door had been thrown open. Though from this angle I could not see inside the entryway, there was a wedge of brightness painting the canyon floor in that ungodly shade of blue that the enchanted torches burned to mark the passing of any living creature within their ancient walls. The shock weakened me and I fell the last half dozen feet to the base of the cliff. It was the noise that upset me more than the pain: the sharp crack of a bone snapping, and the pathetic mewl I let out because of it.

Sheer godly providence might have been the only thing to save me then, as I lay there for some minutes, reduced to trembling and another bout of vomiting. I burned bright with resentment towards my brother, but force of will could not erase the fact that he had done a fine job of crippling me. I made it to all fours and began to crawl forward under the impetus of my flickering anger. It was at that moment when someone lifted me by the arm and set me fully on my feet again. “Well, waxing and waning, it is you!” said a booming voice. “Are you alright, Aserios Mala?”

“No, fool, I’m dying!” Had I not vomited most of my wit, I would have corrected his pronunciation: he could at least let me die under the title I had spent so many years striving for.

“And yet you fight it with every breath. Fine work.” I’m sure he meant those words to be heartening, a gesture thoroughly undone by him clapping me roughly on the back, which sent waves of icy pain down my arm and had me swearing like a novitiate. My elbow vibrated discordantly and I realised what had broken in my fall. Could I still use that magic if my arm was no longer whole? No time would be better to find out.

My impromptu rescuer had been jabbering this whole time about the chaos unfolding back at the camp: according to him the soldiers were in an uproar with the lieutenant dead, several fires had been set, and all animals in the train had been let loose. So, he had had help. He had administered the death while his cohort had sown the seeds of chaos to trap us all here. Karrigan had grown more devious in these intervening years.

Partly in an effort to escape this litany of disasters, I had resumed my steady trudge toward the great doors of the ancient ruins carved into the cliffside. I was only slightly surprised to hear the ring of chainmail close behind me. “Mala, I cannot allow you into the ruin. We have strict orders about the retinues. For your safety.” He walked briskly alongside me as I pushed my aching, sweating body to move quicker. I admit, I was disoriented when I shot him an incredulous look and was answered by a wide grin and a puff of the chest.

“According to you, going back up to the camp would be equally as dangerous.”

“I agree, but there’s a dragon in that place, not just fire.”

“How insightful. Unfortunately, that dragon requires someone with magical skill to destroy it. And I’m sad to say that, of the two of us, the only one capable, is me.” While explaining my reasons, I had continued on my path, and now was stood at the threshold of the ancient complex that had spawned so much madness and grief. The huge façade was painstakingly chiselled as if a city of many storeys had been built, then somehow swaddled in stone. A dozen empty archways hid thick shadows, tiled floors long bled of colour were thick with dust, and the two huge doors stood ajar enough to admit two men abreast. Thirty feet high, blasted dry by sand or rain, both had been forced open to reveal the dingy space within. The arched tunnel reached back into the rock and was lit by rows of crackling, seemingly unsupported flames in a sickening shade of blue-green.

The solider appeared at my shoulder as I narrowly conquered a moment of nervousness. His mail rattled and drew my eyes. He was roughly shaven and lightly caked in soot. A stout creature with a sturdy jaw, he was precisely the sort of bulwark that one expected a soldier to be. He had to look down at me for being so large, and the stab of annoyance that this caused, lent me a power that unfroze me. In a moment of daring, I plunged into the tunnel of green flames.

Despite those unnerving scones and their lively flames every few yards along the wall, the light within the chambers was far from adequate. I suspected that the twisting nature of the corridors, the many nooks for shadows to swell, and the disgusting, unnatural colour of the fires was all intentionally designed so as to dissuade interlopers with jittery nerves. The intricately carved reliefs on each side muffled any sound so that silence was like a thick blanket enveloping me, and shapes morphed as the torches danced mockingly. Curves and points made ceilings disappear at unknown heights and the shapes of everything above my head entirely uncertain. There could be large holes with predatory eyes glaring down at me, there could be snags and slopes waiting to swipe my feet from under me. Every step in the whisking shadows was a test of faith, and the light refused to reveal enough to stop the relentless trial.

I had been dreading this moment, but the necessity of a new light source forced me to capitulate. I drew a sharp breath, bit my tongue, and loosened my grip on my injured arm so that I could try to move it. I had been holding it in such a way as to protect it from further injury, but now I needed to know what limits had been imposed on it. My muscles felt disconnected from my mind as I tried to bring the hand of my broken arm up to the other. The blunted fingers scrabbled along the skin of my strong arm, and numbness evaporated in favour of slicing pain as my hand fumbled over the flesh. I felt the awkward new shape of the bones and the tender, aching muscles around the misaligned joint, all straining as it fought to move them to my desires. By memory I found the tattoo just below my wrist and squashed my fingertips to the spot. I retracted them hurriedly as the pain flared in the bunching muscles of my moving arm. Then I let my breath out in a sigh of relief, for as I lifted my hand into the air before my face and snapped my fingers, a ball of shimmering white light bloomed in my palm.

The spell had worked despite how my left hand had been reduced to a blunt tool. I could not twist or wave that arm to move the light, but it was at least large enough to shed greater brightness, and allow me to see the damage to my elbow. Miraculously, the skin was not broken, but it was beset by swelling that threatened to deform one of my other tattoos. The depiction of Taa Mira the Eagle was beginning to bend beyond its normal limits. I could almost feel the spell fading from that patch of my skin, pain pulsing through the lines of ink as they distorted. I suddenly felt the sharp pressure of time running out.

I pressed my injured arm against my chest in preparation to run to Karrigan, just to be done with this madness. Before I went a single step, the blocky face of the soldier loomed from the shadows near to my face. I started and in an undignified display, was forced to spit a mouthful of bile from my jittering stomach.

“Wow! Aserios magic!” His voice was so cheery that it was grating. “Is that what will kill this dragon? This light?”

Staggering to my feet, I tried to glare at him. Part of me wanted to blurt to him that even the Aserios Sinse’ala could not kill a dragon, but between the poison and the pain, I could not summon the malice required to reveal the truth. I did not want to spread that knowledge, and a wise man would not ask to be burdened with it. I stared at him but his smile did not slip. Grinding my teeth, I managed to move my crippled hand enough to fire the light down the corridor. I garbled an assurance that I would fight as well as I could, then hurried around the corner where my light had flown. I heard the soldier laugh and bellow at the shadows “to the fight! To the fight!” Without a moment’s hesitation, his heavy, running steps came barrelling past me. His mail shining like a living constellation, and the echoes of his laugh creating a haunting chorus. He seemed like a moon-blessed army of my very own. Though I still did not trust his blind faith, I suddenly found it blissfully easy to press on.

The ruins twisted like dire arteries spiralling out from a black heart. Had I not sacrificed many sleepless nights to memorising the layouts of other complexes, I would have been lost among their many coils. As it was, I found no fewer than five dead ends and the stress of time wasted made me vomit again. I was exhausted by the ravages of Karrigan’s poison, but after spitting remnants of it all over the masonry, I dared to believe that the pain of it had faded. At least, it had dulled compared to the repeated flares of pain that came from my fractured elbow.

I confess, I was grateful for the soldier’s presence in those moments. When frustration halted me, he ran ahead like a beacon; when nausea staggered me, he returned to set me upright. I appreciated the small displays of help that allowed me to adhere to my word. Even his constant chattering took on a pleasant air, being the only sound of life in the ruins with me. Trapped in there with darkness wrapped about me like a cloying shroud, forced to listen to the blood roaring in my ears, it would have been easy to give in to the desolation that pervaded the air. There was a horrible stench on the air: dust and mould and the must of an ancient place undisturbed. It was choking, and I could taste the decay in my throat.

As we ran through the tunnels, I suddenly notice a change in that foul air. A finger of a chill breeze spirited along the corridor and passed us. I marked its passing when the solider balked. He raised his free hand over his nose and tried to use the other to make the sign against evil behind his buckler. “Waxing and waning,” he sputtered, “what is that smell?”

I forced a laugh as I pressed myself through a narrow gap in one cracked wall mural. “Did your trade not teach you what death smells like?” I fired back sarcastically. My light squeezed through the gap over our heads, and the funnelling of its brightness made our shadows into waving monsters on the wall that greeted us at the end. We emerged into a large circular chamber that was absolutely covered with carved reliefs. Each one stretched from floor to ceiling and featured huge, scaled monsters engaging in terrible acts. They tore through knights with their ferocious claws, they belched jets of fire setting forests aflame, one threw a screaming man into the air with hungry jaws waiting for him to fall. I tried to mask a shudder, and cradled my broken arm close to my chest again.

While I inched my way into the centre of the room, the soldier had been drawn towards the carving of the feasting dragon. I could not see what emotion twisted his face but I fancied that there was a defensive hunch to his broad shoulders. He must have felt the same apprehension that began to creep upon me as I reached my target. My interest was taken, not by those imposing sculptures, but by the stout stone well-constructed in the centre of the room. It was a granite obstacle a little taller than waist-height, with seven sides. Each of those sides was cut with an alcove that had once held something, and there were vaguely familiar runes etched about those niches. I could not truly read the words, but I knew them to be the markers of a dragon birthing pit. When I leaned over to peer into the mouth of the well, that same cold breeze pushed back against me. It carried the stench of death unattended, making me unwittingly think of uncovered corpses abandoned to the mercy of the dry air within the ruins.

“Are dragons truly like this?” The soldier’s voice distracted me and I looked up to find him staring into the shadowy eye of the relief that bared its jaws to snatch its falling victim. When I did not answer right away, the soldier spoke again, but I noticed that he did not turn to me. He tried, or made a slight motion as if he would, but his eyes remained rivetted by dire fascination. “I know all the hymns and swore all the vows. I just wondered. You hear a lot in the old songs that… Well.”

“You don’t believe the fables of the broken moon or the celestial sword?” I asked. Most people tended not to admit to such doubts, as apostacy was as good as a criminal offence. And yet, I felt a sick sort of curiosity to hear those unlikely words come from the mouth of a man whose learning revolved around those same stories any moment that he had spare from physical training.

The response was a laugh, and this time the large man turned to face me easily. He grinned again. “What? You believe the songs that say Thasarine the Fireblooded could lift a river like a page of a book and could seduce any man with a flick of her sunny red hair?” Without waiting for a reply, he chortled and shook himself. “I believe, but I ask a great many questions.”

“Your deacon must love you,” I said under my breath as I directed my gaze back down into the well. Even my floating light did not penetrate deep into that dark throat.

“Mala, are you planning what I think you’re planning?”

“Perhaps you can tell the credulous that I walked on the breeze. If either of us escape this place,” I said. I had to grind my teeth as I raised my working hand ready to siphon another spell. I hesitated as I anticipated the pain – and not just the pain of making the spell from its spot on my shattered elbow, but the landing that awaited me an unseen distance below me, and the inevitable death when I found the dragon in its den. Why was I wasting my efforts here? Aside from my adoration of the title I carried, I knew my conscience would not let me turn away no matter what pains awaited me. Truly I was caught in a riptide, treading water.

In the pause, the solider saw my trepidation and I heard the scuffing of his boots as he hurried to join me at the crown of the well. We both stood with our feet right at the edge of the inside lip, but one of us stared down with courage. He looked at me with that smug, unsufferable grin, and held out his sword hand to me. His lack of apprehension made me concerned that he was a fanatic after all and simply did not realise what those carvings meant, but nerves would not prevent his end in this accursed place. I nodded to him in gratitude, and clamped my free hand about my fracture. I spat a curse for how the jolt pained me deep in my marrow, and them yanked my palm away. I twisted my body so that my right hand could grab his, and I pulled his fist hard against my chest. In the same motion I stepped backwards into the opening of the well before my logical mind could list the reasons not to do so. Gravity took a fistful of my clothes and yanked me down, dragging my compatriot with me. But the magic held us upright as the wind whipped past us, and it slowed our descent when finally the twinkle of sand drew near to our feet.

At least, that was how the flight spell of Taa Mira was supposed to work, but mine was stretched and twisted over a mangled joint, and the bones threatened to pierce the skin and break up the lines that manifested the magic of the great constellation. The descent was wobbly and fraught with collisions against the sides of the huge chute. We tumbled so fast that I feared the spell had failed entirely, only to slow with an obvious jolt that threatened to disgorge the rest of my stomach contents. We thudded to the ground and the sand hissed as it fanned out from our impact. I collapsed to my knees and cried for the pain in my arm. This time I did not need to look to know that the markings were torn. There would be no flying out of here.

Confusingly, this chamber was as bright as the daylight courtyard far above us. The lights glowed green-blue with the same strength as the sky itself. We could see the piles of sand that filled the space like misaligned teeth, the dunes twinkling as they shifted and whispered. The light reflected darkly off of a huge lump in the centre of the room, revealing something that made me quake like a child. Surrounding the dune in which we had landed, was a huge array of bones that was macabre evidence of the rituals conducted at this place in antiquity. Many dozens of skeletons were arrayed against the walls and in smashed open coffins where decades of interments had taken place. This lower chamber was full of death, leeching its foul stench into the rooms above, but it was no mere burial ground for the innocent to be remembered.

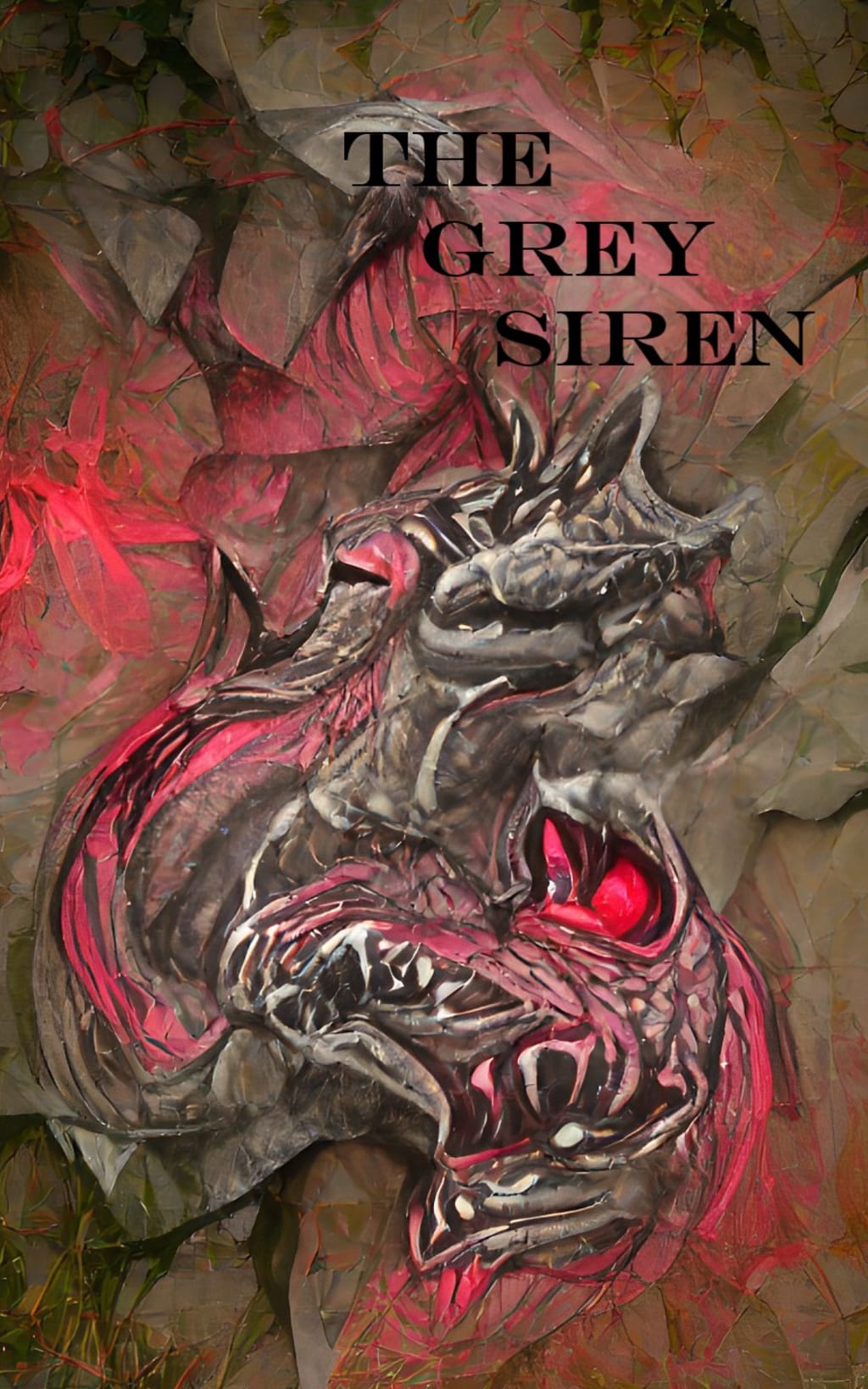

These poor souls, either by choice or by force, had been remanded to this unholy place to serve as seeds for the dire rose that was a dragon. The solider and I stared in abject horror as we saw those bones rattle and rumble across the flagstones and the sand, jouncing like there was a silent whirlwind snatching them all from their places of stillness. They smashed together at great speed, pulled by thousands of tiny hands into a horrible amalgamation of rot. Each fragment, each bone, each shard clinked into its predetermined place, and siphoned the flickering blue flames until each crack was limned in those impossible flames. We were watching a dragon be built from the mountains of death laid about the chamber, the fire of its life kindled by those snuffed out on the land above. And stood there at the feet of the swirling storm, was the architect of this wretched construction, the villain who had taken advantage of the unwitting to forge this creation.

Karrigan craned his neck to peer at us over his shoulder. He was forced to stay crouched on his knees as the bones rushed by close enough to ruffle his hair. Flames gushed by him, lighting his skin in patches of brightness and shadow that threatened to leave awful burns as a punishment for his hubris. His gaunt face was twisted into a caricature of shock when he spotted the two of us landing in the midst of his wicked ritual. His hand twitched at the edge of his hood, and when my eyes were drawn to that robe he wore – identical to mine in almost every way – I felt fresh fury explode in my chest.

I had no strength left to show him kindness or understanding. I had no wit left to divert to calm discussion rather than viciousness. I was reduced to smouldering in fury at the knowledge that this man, my own brother, had taken the knowledge bestowed upon him by his betters and twisted it to this end that most madmen and unhinged prophets would realise was little more than a disjointed dream. My own flesh and blood had stolen the unlived potential of dozens of soldiers and servants and animals who had never done him any wrong, and spent those lives like ill-gotten coins for his own benefit – or worse, for no benefit at all. Watching the thousands of bones and lights congeal into a beast with wings and claws and fangs, I could find no possible reason to want any of this. And some thread inside me snapped with a silent yet deafening twang.

This time, when I moved my ruined arm, I felt no pain whatsoever. The magic felt bottomless as I drew it from deep within my skin, and it felt euphoric to let it fly from my hand. It was not my brother that I was striking – it was a common murderer with delusions above his station. The soldier leapt in the wake of the spell that I loosed, his sword in hand and his buckler raised. He had not waited to demand an explanation, but trusted that I was acting in good faith. A good thing too, as I could not have explained how two Aseriosi had come to blows, and why one was justified over the other. Perhaps he carried his own grievances after watching his countrymen and his fellow men at arms be felled with the poison and that moved his feet. I did not need to know his reasons, only that he had faith.

Karrigan had not expected to be interrupted, much less to be met with force. An invisible wave of force slammed into him and threw him into the maelstrom of bone shards. He barely had the time to scream. I strode forward while pulling a light from the skin of my other arm. The solider whirled his sword with practiced grace, chasing after the spot where Karrigan had vanished, and instead chopping at the carapace that was forming right in front of us.

I threw lights around the chamber until not an inch remained where a shadow could hide. I regretted revealing the fruits of Karrigan’s labour, but I had no choice. I knew that the dragon, whether it worked or only half formed, needed to be destroyed. I had known back when I first ensured that my name was chosen on the ballot of volunteers for the journey. I could not allow a dragon to rise in this place – I had to prevent some inexperienced fool from gaining control of a horrific necromantic fusion.

Obviously I would need the soldier’s help, and the bright flashes of his blade proved to be a fine distraction for the claws and forelimbs that were swatting blindly down at him. He did not so much as shiver when he was confronted by this: a headless, half-formed torso larger than a bear, that was swinging wings and clawed feet at him like a beast in its death throes. It was ironic since the amalgamation was just now being born, and the soldier had likely never faced anything other than men of different sovereigns. But the two, man and monster, danced about one another with steel flashing in claws and sword, and my mystical lights threw the whole affair into sharp relief. Flecks of blood flew on the breezes, sparkling like tiny rubies.

I could hear Karrigan screaming, both in pain and in indignation as I began to spit spell after spell at him. I tried burning the construction with cold fire, but they appeared immune to the lick of flames. I used telekinesis beyond any bounds I had attempted before, in the vain hope of prying individual bones from the creature. I thought that if I could undo what the trapped spirits were building, I could stop the inevitable. That was my moment of foolishness – Karrigan had started an insane process and I knew that it could not be stopped, but still I tried. The air about me was full of flitting fragments as if I stood amidst a cloud of locusts rather than sand and bone, and I could not help but shriek at the dozens of gashes that sharp edges tore in my skin. The fear of losing another tattoo to this made me retreat into my robes like swaddling, which in turn brought fresh waves of pain through my broken elbow. Angry, yet helpless, I hunched against the endless wind of broken remains.

My self-pity was interrupted by a roaring scream, and mere seconds later the storm stopped as suddenly as a peal of thunder. I staggered towards the soldier, who was still on his feet yet sagging hard. His sword planted point down in the mortar of the flagstones was the only thing preventing him from collapsing – his exposed skin on his face and hands was crisscrossed with slices and tiny rivulets of blood ran down his skin in all directions where he had been viciously ducking and swinging to try and eke out some amount of damage on this impossible foe. A light yet clumsy touch on his shoulder earned me a weak smile, the kind that was in blatant denial of reality, and a rasping whisper of “I’m not yet dead”.

His assessment was given an air of hubris when that scream came again and our eyes were drawn up to the monstrosity standing over us. Entirely untouched by the sword or the magic used against it, the dragon was almost complete: bones and flickering flames had melded together a deep chest, muscles legs and raggedy wings. The construction stopped at the shoulders, but that had not hampered its movement. However, the scream grew louder and swiftly revealed the final touch that was needed before the dragon could be complete. Karrigan re-emerged from the sharp, pointed insides of the creature, and rose into the headless space as if a hidden hand had pressed him into a niche carved specifically for him. He thrashed like a condemned man, and the limbs of the creation jerked sporadically for a few moments. The soldier dragged me backwards from the flailing claws, but I saw clearly that it was Karrigan taking control of the huge amalgamation. His scream shifted higher in pitch as the realisation struck him with keener pain than any of his other actions. This, the pinnacle of his wickedness, was the part that he could not face. He, the chimera, launched into the air like an arrow, and the wind threw me to the ground with the strength of ten men.

For a long time after a regained my breath, I lacked the strength to do anything more than stare at the gouge the impossible beast had blasted in the wall as it threw itself at the stone to escape the pit of death. I had failed to kill the dragon, and could scarcely understand how my own brother had stolen it away. I was reduced to cynical laughter as I realised that the only thing worse than now hunting Karrigan to complete the wretched task, would be explaining this monumental failure to the king.

Comments