The Forgotten Room

Where Silence Unlocks What Time Forgot

The Forgotten Room

The first thing they take from you is your voice.

“From now, until the end of the retreat,” the teacher says, “no speaking. No reading. No phones. No writing. No eye contact if you can avoid it. For ten days, you will live only with yourselves.”

We’re seated on thin cushions in the meditation hall, a loose horseshoe of strangers in comfortable clothing. Someone’s ankle cracks as they try to cross their legs. A woman near me sniffles. A man to my left scratches his beard like sandpaper on cardboard. The woman in front of me has a tiny hole at the seam of her T-shirt. I stare at it as if it might open and swallow us all.

I press my fingertips together, feel the slight tremor in my right hand. It’s subtle now, almost invisible. Months ago, in the hospital, it was a storm. Half my face melted, words fell out of my mouth in the wrong order, the world tilted. Stroke. One clean, brutal syllable.

My speech mostly came back. My balance mostly returned. But something in me never stopped listing sideways.

So here I am, voluntarily silencing myself in a world that already feels unreliable.

The teacher rings a bell. Its sound stretches through the room like a line drawn in water.

“This silence,” he says, “is a door. You don’t need to force anything. Just notice what arises when you stop running from yourself.”

By the second day, I understand why people run.

Silence outside does not mean silence inside. My mind hurls itself from wall to wall like a trapped bird. It pecks at lists and worries, flutters against old embarrassments. It resurfaces hospital smells, the sticky rasp of plastic tubing in my throat, the way my son’s face crumpled when he saw me.

I am meant to be following my breath, but my thoughts refuse the leash.

Inhale: My boss never called.

Exhale: He sent a text. Just one.

Inhale: We can replace you.

Exhale: Did he say that, or did I?

We meditate, we walk, we eat in silence, we meditate again. No phones. No television. No mixed noise of news and adverts to drown myself in. No distraction from the fact that I almost died and have no idea what to do with the time I’ve been handed back.

On the third afternoon, during a walking meditation, the image comes to me.

A house. Not any house I’ve lived in, but a composite—brick and weatherboard, familiar and wrong. Its corridors are lined with framed photographs, most of them blurred when I try to look closer. At the end of a hallway, there’s a door with peeling white paint and a brass handle gone dull with age.

I know, instinctively, that I have not opened that door in years.

As I pace the gravel path outside the hall, placing each foot slowly, deliberately, heel then ball then toes, my mind keeps circling back to that door.

The Forgotten Room, a quiet voice whispers.

Not a metaphor I invented. I’ve heard it before.

My therapist spoke that way. “We have rooms we live in every day,” she’d say. “Our kitchen worries, our office fears, our bedroom dreams. And then we have rooms we never visit. They don’t disappear. They wait.”

I stopped seeing her when things got “busy.” Busy meant avoiding. Busy meant building years of distraction over something I clearly didn’t want to see.

Apparently, silence is a crowbar.

On day four, I wake up furious.

I’m angry at the teacher for his calmly folded hands. I’m angry at the cook for the bland porridge. I’m angry at the woman in the next room for breathing too loudly through the paper-thin wall.

Mostly, I’m angry at myself—for needing this, for breaking in the first place, for not being stronger, wiser, better.

We sit through the morning session as the light seeps into the hall. My right hand trembles on my knee. It’s mild, but enough to pull memories to the surface: my daughter’s eyes when she cut up my food for me, the way she tried to pretend her hands weren’t shaking too.

Anger is easier to hold than shame. Easier than fear.

“Notice the feeling,” the teacher says. “Name it gently. Let it show you its roots. Notice it then let it pass.”

I try. I sit and breathe and name it—anger. I watch where it lives in my body. A clenched jaw, a tight chest, heat behind my eyes.

Then I feel something else, something deeper, like a weight on the floor of a lake.

Underneath the anger is a kind of exhausted grief.

It is at that moment—when I finally stop wrestling and simply let myself feel stupidly, freely sad—that I find myself standing, in my mind, in front of that white door again.

I don’t open it. Not yet. But my hand lifts toward the doorknob.

The days blur.

We wake at half past four. We meditate. We eat. We meditate. We walk. We meditate. At night, we sleep early, though sleep is not the right word for the thin, restless drifting that comes.

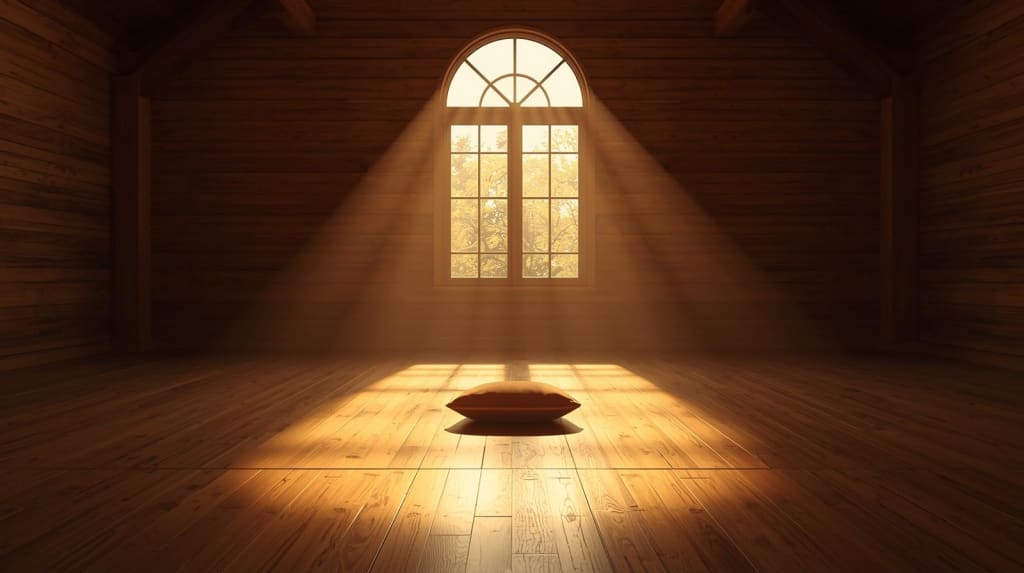

In the absence of conversation, small details swell to fill the space. The way the afternoon light slopes across the floorboards. The sound of someone’s stomach growling two cushions away. The faint scent of earth drifting in through the open window.

Without news or social media, the world shrinks down to this patch of earth, these forty strangers, my own head.

By day six, my thoughts have begun to feel… less solid. They still come, but they pass more quickly, like clouds instead of stones. I can see them as events rather than truths.

You’re a burden, says one thought. Another voice, softer, replies: That is a sentence you learned, not a fact.

You wasted your life, says another. And again: That’s one story. Is it the only one?

Sometimes, during the longer sits, blank emptiness washes through. It’s not peaceful, exactly; more like someone turned off the lights and left me with the hum of the fridge. In that dim silence, images rise unbidden.

My father in his armchair, smoke curling above him like a question mark.

My first classroom, plasticene on my fingers.

The swimming pool, me and my mates, trying for the highest bomb.

And always, always, the house in my mind. The hallway. The door.

On the seventh afternoon, after lunch, something shifts.

We’ve just finished another hour of seated practice. My legs are pins and needles. As the gong fades, we stand for walking meditation. The room moves in slow motion, bodies unfolding like stiff origami. No one speaks. The shuffle of feet is its own language.

I take my first step and suddenly I am ten years old, standing in the dim hallway of our real house, the one with the yellow kitchen and the cracked linoleum. My father’s voice is coming through the walls in sharp spikes. My mother’s voice is softer, but brittle.

I’ve forgotten this, I think.

Except I haven’t. I’ve locked it away.

In the memory, I stand in front of the spare room at the end of the hall, the room where no one ever goes. The door is half-shut, a stripe of darkness behind it. My hand hovers near the knob. I want to go in there, because it is the only place in the house where no one is shouting.

But I don’t. I stay in the corridor, soaked in other people’s fear.

The memory and the present blur. For one disorienting moment I am both the child and the adult, both in that old hallway and on this wooden floor.

The forgotten room is not just a metaphor. It is a room that once existed, a sanctuary I never claimed.

The child-me turns away from the door. The adult-me wants to scream: Open it. Please. Go in.

I cannot change what she did. But here, now, in the quiet of the meditation hall, I feel a strange permission—like the past has loosened its grip just enough to allow a different ending, even if only in my mind.

So I imagine it. I let the scene replay with one alteration: she turns the knob.

The door opens.

Inside, the room is smaller than I remember and larger than it should be.

Dust motes spin in the shaft of light from a high, narrow window. There’s a single bed with a faded quilt, a small wooden desk, a bookcase with three books: one about birds, one about the human body, one about fixing things. The air smells faintly of lavender and old paper.

In this imagined memory, the shouting in the hall is muffled. The house is still the house of worry and unpaid bills and my father’s unspoken terror of his own blood. But this room—this room is strangely untouchable.

It feels like time paused here and forgot to restart.

I can see myself, a child, sitting on the bed. I can feel the weight of a book in my lap, the realisation that the human brain is not a single, solid thing but networks of pathways. That damage can alter it, that sometimes it recovers, sometimes it doesn’t.

In the real past, perhaps I never opened that book, never sat on that bed. But here, in the soft theatre of my mind, I watch that younger version of myself discovering something crucial: that nothing in a human life is inevitable.

Not the way my father drank. Not the way my mother disappeared into worry. Not, even, the way I would one day treat my own body like an afterthought, pushing it through long hours and postponed check-ups until a blood vessel protested.

The room becomes a container for all the things I didn’t know I knew. For the awareness that, even then, part of me understood there were other paths. That I wasn’t completely powerless, even if I felt like I was.

Standing in the centre of the room, adult-me feels the ceiling stretch, the walls breathe. The forgotten room shifts from being a vault of locked pain to something else: an archive. A place where memories are kept—not to haunt me, but to be seen, understood, refiled.

I feel my chest loosen, as if some tight band has snapped. My eyes prickle.

Back in the meditation hall, on my slow, measured step, tears slide down my face. No one looks up. Everyone is absorbed in their own inner houses, their own halls and doors.

I do not wipe the tears away. I let them fall. They feel like dust being washed from old floorboards.

On day eight, the teacher gives a short talk after the evening sit.

“People sometimes think of meditation as escape,” he says. “A way to float above the chaos. But that’s not it. Meditation is a way of entering the rooms we avoid. The ones we locked when we were too young, or too tired, or too hurt to stay there.”

He glances around the room. For a second, his eyes pass over mine.

“When you go into those rooms now,” he continues, “you do it with the wisdom and kindness you didn’t have then. That’s how the past stops running the present.”

I feel seen and slightly betrayed, as if he has been spying on my private visions.

But of course, he hasn’t. The architecture of avoidance is common. Only the furniture differs.

That night, lying in my narrow bed, I wander the house in my mind again.

Some rooms I know too well: the one full of work stress, buzzing with fluorescent lights and unanswered emails. The one of hospital fear, walls painted a nauseous institutional green. The cramped cubby of shame, plastered with everything I’ve ever said wrong.

I move through them more gently now. I don’t slam their doors or sink to the floor. I just walk, noticing.

Eventually, I find myself at the end of the hallway again, in front of that white door. This time, I don’t hesitate.

When I open it, the room has changed.

The dust is gone. The bed is made. The desk holds a notebook and a pen, though in this retreat I’m not allowed to write. Still, their presence feels like an invitation to another kind of future, one where I might document instead of bury.

On the wall, there’s a mirror.

I approach it slowly.

For months after the stroke, I avoided mirrors. I didn’t want to see the lopsided weakness, the slightly off timing of my smile. When I did look, all I could see was damage and failure and the looming threat of another attack.

Now, in the dream-room’s mirror, I see… myself.

Not the before version or the after version. Just the current one. Hair thinner at the temples. A faint line where the hospital tape rubbed the skin. A right hand that still trembles a little when I’m tired.

Behind my eyes, I see the ten-year-old with the book about the human body. The teenager who left home as soon as she could. The young woman who worked extra shifts and swallowed panic. The middle-aged person who ignored dizziness until her words slurred on the phone.

They are all here. They all lived in me. They all did the best they could with what they knew at the time.

“I’m sorry,” I whisper in the quiet of my mind, though my physical lips do not move. “I’m sorry I treated you like a problem to fix instead of a person to care for.”

The mirror doesn’t answer. It doesn’t need to.

The apology lands somewhere deep, like a key turning in a long-rusted lock.

The room brightens, not with any theatrical glow, but with a simple clarity. I understand, in a way that feels almost physical, that the story I’ve been telling—this is just who I am, this is how it always turns out, everything is inevitable—was never the only script available.

The past happened. I can’t rewrite events. But I can rewrite the meanings I hung on them, the conclusions I drew about my worth, my agency, my future.

The forgotten room turns out not to be a prison after all. It’s a workshop.

On the tenth day, they give our voices back.

We gather in the hall after breakfast. The teacher explains that noble silence will end after the next gong. He encourages us to be gentle, to ease back into speech rather than explode into it.

When the gong rings, the room erupts anyway.

It’s a soft eruption, more like fizz than explosion. Laughter bubbles up, tentative greetings, the hushed joy of trying out words again. Some people cry as they talk, overwhelmed by the sound of their own voices. Others stand back, watching, hands wrapped around mugs of tea.

My right hand still trembles when I lift my cup, but I don’t hate it anymore. It’s just a reminder: a trace of the storm I lived through.

A woman with grey-streaked hair approaches me.

“Hi,” she says, a little shy. “We sat near each other all week. I hope you don’t mind me saying—you seem… different than on the first day.”

I blink. My throat feels rusty.

“How so?” I manage, my voice lower than I remember, but steady.

“Lighter,” she says simply. “Like you left something heavy behind.”

I think of dust motes, of old quilts, of rooms finally aired out.

“I think I did,” I say.

We talk a little, about nothing and everything. The food. The early mornings. The boredom and unexpected beauty of listening to your own mind. It feels strange and precious to be able to share even these small things.

Later, when I’m packing my bag in the small, plain room where I’ve slept, I realise I am not scared to leave.

Before the retreat, the future felt like a long corridor lined with doors that all led to the same place: burnout, illness, disappointment. Now, it feels less predetermined, more like a house I can rearrange.

I slide my phone out of the sealed envelope I surrendered on the first day. It feels heavier than it did before. I don’t turn it on yet.

Instead, I sit on the bed for a moment, eyes closed, and step back into the inner house.

The forgotten room is no longer forgotten. The door stands open. Sunlight lies in a clear square on the floor. The desk waits. The mirror waits.

I know I’ll close the door again sometimes. I’ll fall back into old patterns, old stories. I’m human. Habit is stubborn.

But now I know where the room is and how to get there. I know that inside it are not monsters, but memories that grow less frightening each time I look at them with the eyes I have now.

As I stand up and lift my bag onto my shoulder, my body feels the same and different, both.

The stroke is part of my story. The fear in my parents’ hallway is part of my story. The years of avoidance are part of my story.

But they are no longer the whole story.

Out beyond the retreat, beyond the gravel car park and the narrow road and the city waiting like a flood of noise, a new chapter is opening. It will still contain hospital appointments and maybe more tremors. It will still contain losses I can’t predict.

Yet it will also contain pauses. Rooms I enter on purpose. Meanings I choose.

I walk out of the building into the bright, ordinary day. The air smells crisp and fresh with eucalyptus and possibility.

Behind me, in the quiet architecture of my mind, a once-abandoned door stays open.

The forgotten room is no longer forgotten.

It is part of the house of me, and I am finally, consciously, moving in.

Comments (1)

Such beautiful writing! And a powerful message, ‘’I’m sorry I treated you like a problem to fix instead of a person to care for.”