The Eighth Day - Chapter 2: Gospel in Ink and Wax

By S.L. James

Chapter Two: Gospel in Ink and Wax

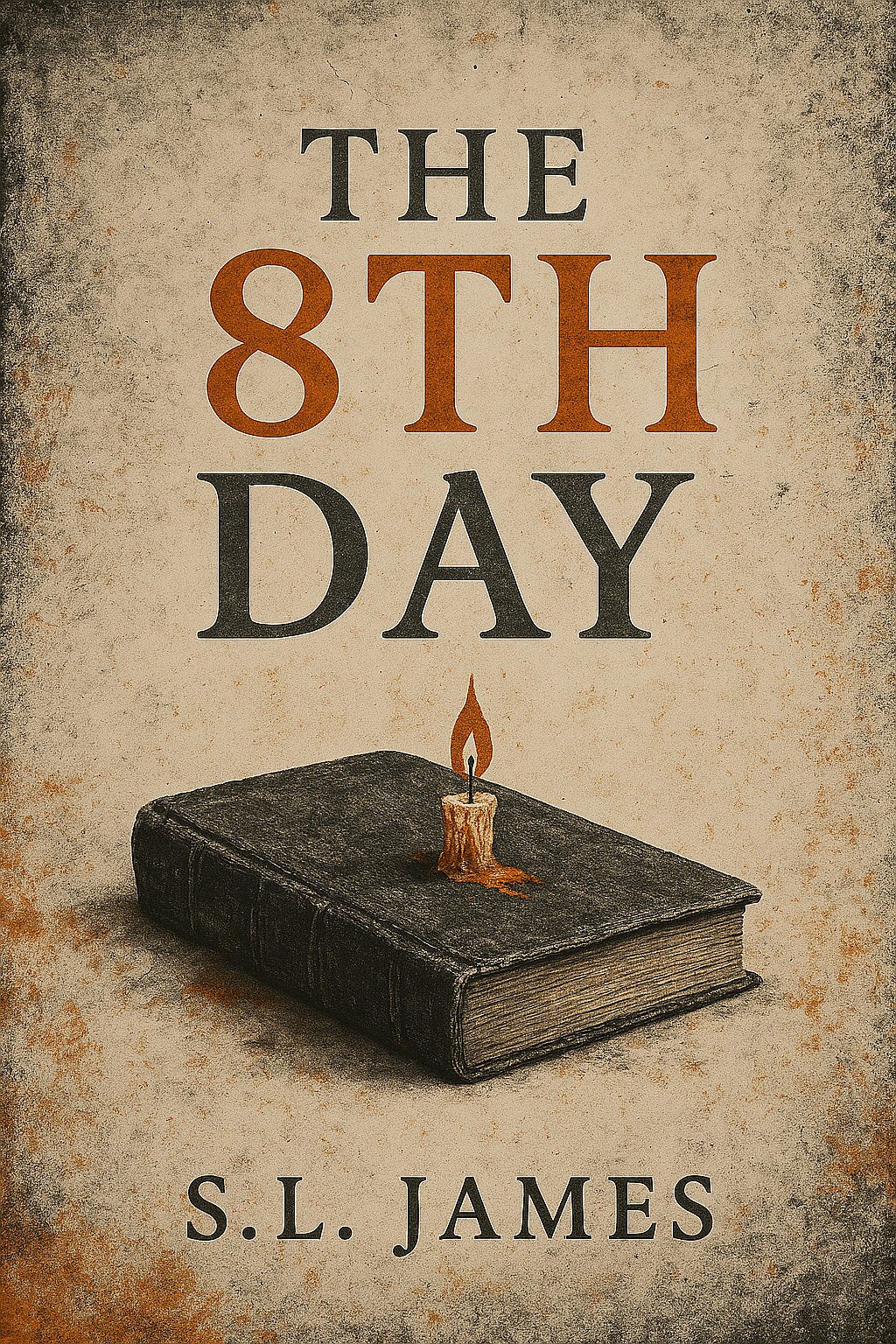

Scene 1: Resurrection by Iron (They do not rebuild a machine. They resurrect a defiance smothered by centuries.)

The chamber breathed like a wounded lung. Every draft of air filtered through stone groans and soot-wet cracks, carrying the scent of ash and something older, mildewed parchment, spent wax, and the stale copper tang of memory. The monastery had no windows here, only slits of light from above that haloed through the dust like divine judgment.

Séraphin stood before the press like a man awaiting confession, shoulders sloped with reverence and war-weariness. The machine loomed before him, rusted, half-disassembled, smeared with soot and sacrament. It had been buried beneath the altar for decades, perhaps longer, hidden by generations who feared what it could unleash.

Camille flanked him, candle in one hand, the other resting on the hilt of her dagger, not as threat, but as ritual. Her breath fogged in the chill, yet she stood steady as a statue carved from intention. Moss crouched nearby, sleeves rolled to the elbows, threading spools of ancient ribbon into place with the quiet devotion of a monastic mechanic. They whispered under their breath as they worked, part prayer, part curse.

Father Emeric descended the narrow steps and handed down a rusted wrench from an overhead hook. "It’s older than sin," he said, not unkindly, "and twice as stubborn."

Moss snorted. "Then it’ll fit right in."

Their laughter was brief, brittle, more a memory of joy than its full embodiment. It clung to the vaulted stone like incense, then dissolved into the silence of sacred decay.

The press was no longer a relic. It was becoming again, a resurrection wrought in rust and oil, in bruised knuckles and smoke. Séraphin rubbed a cloth along the platen with the care of a surgeon cleansing bone. The iron’s every groove seemed to remember the work it had once done, groaning with ghosted purpose.

Camille retrieved a small tin of blackened ink from her satchel and opened it slowly. The scent filled the space like old blood and myrrh.

"Smells like revolution," she said.

Emeric brought a basin of hot water from a pipe in the corridor. Steam spiraled up into the dim candlelight, casting warping shadows on the wall, shadows that looked like saints mid-scream.

“There,” Séraphin murmured. “It lives again.”

Moss grinned, but their eyes were glassy with the sheen of something unspoken. “Never thought I’d help rebuild a weapon made of type.”

Camille said nothing. She laid down the gutted hymnal on the slab of stone beside the press. Its pages fluttered open as if summoned by breath. The first draft was laid bare, handwritten in fevered ink, underlined and scratched, the margins riddled with her own notes.

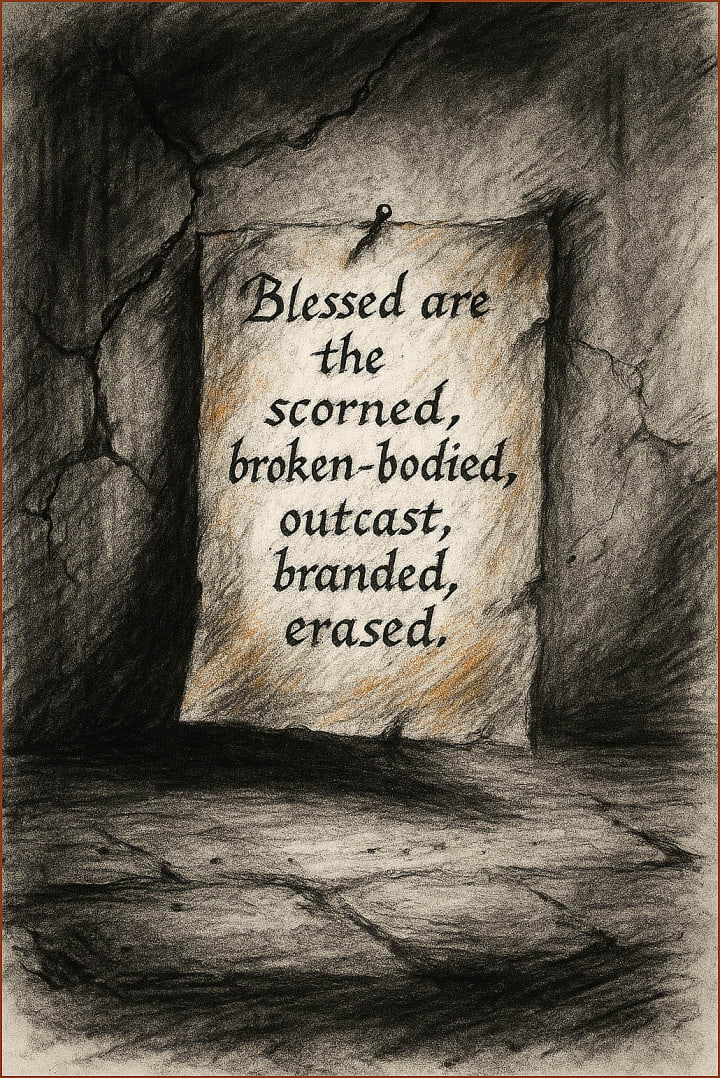

"Blessed are the liminal, for they dwell in both light and shadow.Blessed are the unbecome, for theirs is the Kingdom unclaimed.Blessed are the cut, the spliced, the refused, for they shall carve language where there was silence."

Camille traced a line with her fingertip beneath a particularly jagged phrase. “Too sharp?” she had written. In the corner, Séraphin had scribbled back: “Not sharp enough.”

Moss returned from the press with a strip of handmade paper held between two gloved fingers. “Test print’s clean,” they said. “Shall we make history?”

Séraphin dipped a wooden roller into the ink and pressed it across the block of reversed text, each stroke deliberate, an act of liturgy. Camille adjusted the arms of the press, muscles taut, breath held. When the crank was turned, it groaned with resurrection, exhaling inked truth.

The first page slid out like breath expelled after drowning. It bore the words in stark black:

“The Gospel According to the Unwritten Flesh.”

Moss took it reverently, inspecting every letter. No blur. No bleed.

Camille whispered, "Again. Dozens. Tonight."

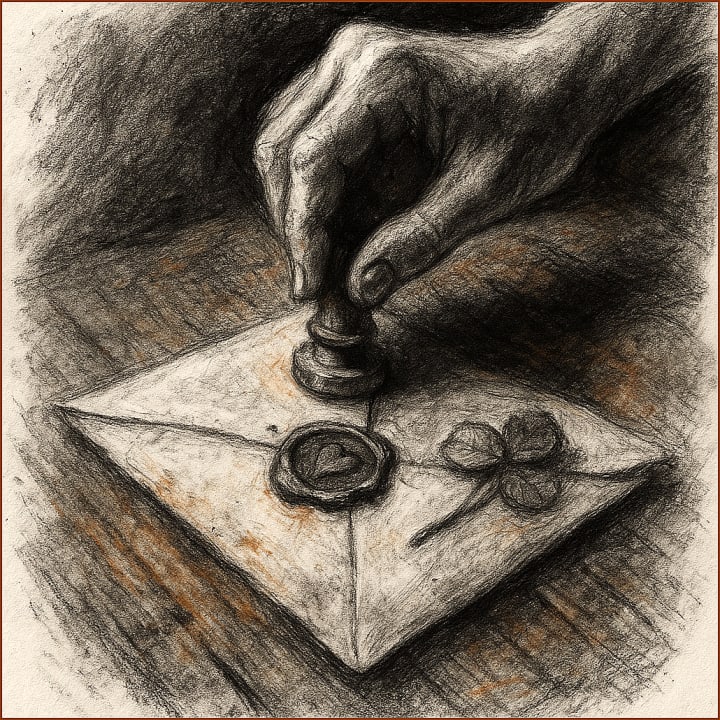

They worked in a choreography of rebellion, inking, pressing, drying, binding, until stacks of tracts sprawled across the slab like wings drying after baptism. Moss stitched each pamphlet with red thread. Camille sealed them shut with wax.

Father Emeric knelt beside them. From the folds of his robe, he withdrew a soft leather pouch. Inside: a metal stamp, small and scorched, shaped like a clover.

“It was theirs,” he said. “The ones who tried before. They didn’t live. But their words did.”

Séraphin pressed the seal into a drop of molten wax. Burnt orange bled into parchment.

Camille handed him another sheet, her fingertips smudged with ash and ink.

Moss leaned against the press, watching it all unfold with something between awe and fear. “We’re not just printing pages. We’re forging scripture.”

Séraphin didn’t look up. “No,” he said. “We’re unburying it.”

And so the underground gospel began, not in cathedrals, but in crypts.

Not with sermons, but with soot.

Not with gold, but with rust and rebirth.

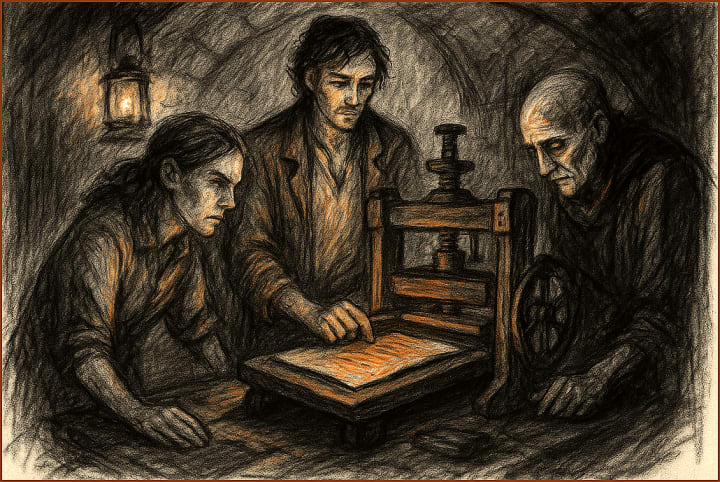

Scene 2: The Rewritten Beatitudes (Where heresy bleeds into hymn, and ash-laced truth rewrites the sacred from the margins.)

The press had blown out another page and the room smelled of incense, thick, holy choking ink. He read again the new line, his lips moving in unison with the words as he leaned over the platen, as in a kind of prayer transferred out of psalms into parchment.

"Blessed are the misnamed, for they know the sting of language."

Each beatitude he wrote twisted the marrow of doctrine, broke the bread of orthodoxy with hands that trembled from memory, not fear. This was not rewriting. This was exhumation.

Camille hovered beside him, one hand on the stone table, the other curled around a quill. She was not merely watching; she was interpreting. As Séraphin finished a line, she annotated it, questioning tone, context, and interpretation with a sharp eye and sharper tongue. Her marginalia became scripture within scripture, challenging and reinforcing in the same breath.

“This one,” she said, tapping the next line, “feels too... polite.”

Séraphin looked. "Blessed are those who do not pass, for they bear the face of God.”

“It should cut deeper. These words need to bleed. They need to blister the mouths of those who read them too fast.”

He nodded. “Then say it.”

Camille scribbled beside the line: "Unseen by man, unmissed by the Church, seen always by flame."

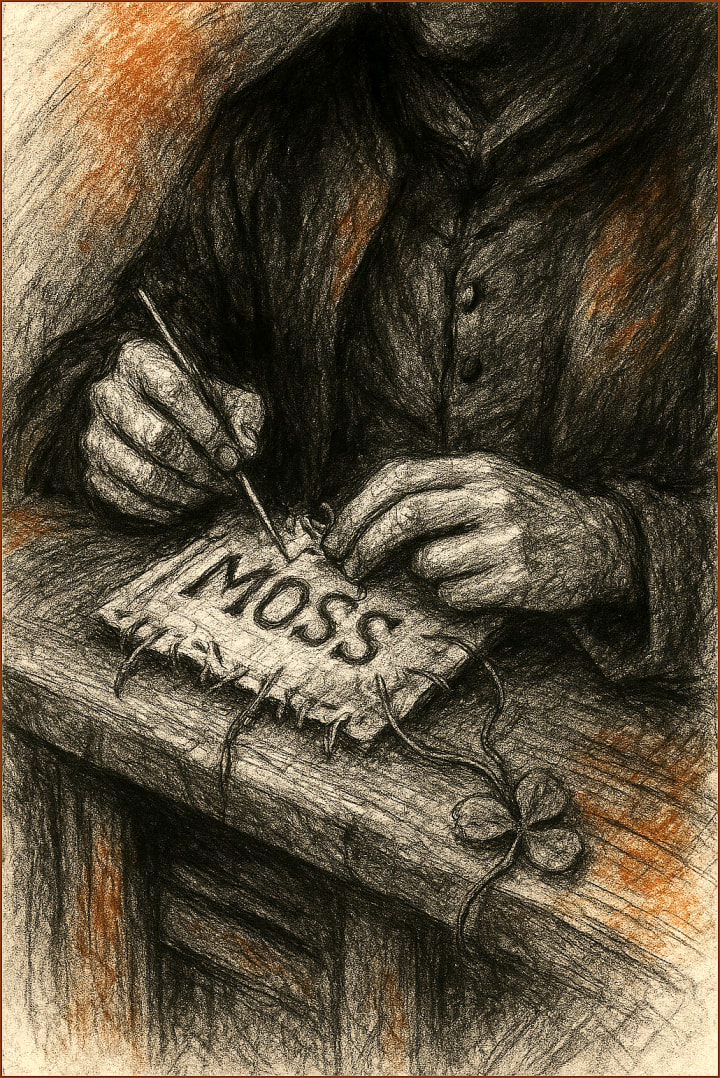

In the corner, Moss sat cross-legged, coat half-off, stitching a red thread through the hem with small, focused movements. Their name, embroidered one letter at a time, emerged like a sigil: M O S S. It wasn’t vanity. It was resistance. It was reclamation. For them, a name sewn was safer than one spoken.

“You know,” they muttered without looking up, “if the Inquisitors catch wind of this, we’re all going to die ironically.”

Camille raised an eyebrow. “Irony’s the only real resurrection.”

Moss grinned. Their hands didn’t stop. The red thread flashed like a vein pulsing through the fabric. Their fingers were already smudged with wax, their palms stained from sealing pamphlets in the firelit corner.

Emeric moved with ghostly precision through the shadows, placing finished pages into a worn leather satchel that had once carried sacramental wine. “No soul ever found salvation without first being damned,” he said quietly.

The pile of printed tracts grew. Each one bore the headline:

The Beatitudes of the Broken Body

Blessed are the surgically erased, for their scars shall rewrite law.

Blessed are the misgendered, for they know the silence between God’s syllables.

Blessed are the heretical healers, for they lay hands upon truth unblessed.

Blessed are the neither/nors, the and/alsos, the both/neithers, for theirs is the dust that birthed Genesis.

Each line was a wound with wings.

Madame Bérénice Duprès arrived unannounced. She moved like folded parchment, elegant, crisp at the edges, and yellowing with secrets. Her shawl fluttered as she descended, the only color in the crypt a faded violet stitched with sun symbols. Her arrival scattered dust and silence in equal measure.

She nodded once to Emeric, then to Séraphin. "My darlings."

She carried no weapons. Only a velvet pouch of wax seals and a ring etched with the emblem of a serpent biting its tail, the courier's mark. She bent beside the growing stack of tracts, eyes shining.

“So it begins again,” she whispered. “The subversion of God by His children.”

Moss passed her a folded page sealed in burnt orange wax.

She pressed it to her lips. “This is what they fear.”

Camille studied her, then asked, “How many safe hands do we have?”

Bérénice smiled grimly. “Enough to begin. Not enough to rest.”

Séraphin handed her the final draft, still damp with ink. She slipped it into her satchel, then removed a journal, blood-browned at the edges, its leather cover curled by heat. On its first page, pressed like an afterthought, was a clover: four leaves, dried and browned to copper.

“This belonged to one of the original printers,” she said. “They died with scripture in their lungs.”

She handed it to Séraphin. “Now it belongs to you.”

He opened the journal, and in it, only one phrase was scrawled at the top:

Write what you are forbidden to live.

His breath hitched. Camille steadied him with a glance. Moss kept stitching.

The press hissed its next exhalation.

Words returned to the world like ghosts turned flesh.

Scene 3: The Names We Carry (In the hush of the Cloister, a needle becomes gospel, and names once silenced begin to bleed back into the world.)

Moss’s needle moved in small, steady jabs, the red thread pulling taut through the coarse lining of their coat. Each stitch was a heartbeat. Each letter formed like a whispered confession—M O S S—not for anyone else’s eyes, but for the ghosts that still curled beneath their skin, for the ache of misnaming that never quite left. They stitched slowly, methodically, the letters rising like a small rebellion.

Camille sat nearby, watching in silence, a candle between them burning low, guttering in protest of the damp. She reached over to steady the flame with her breath, and the gesture made Moss pause.

“You think it’s foolish?” Moss asked, not looking up.

Camille didn’t answer right away. “No,” she said eventually. “I think it’s the only honest thing we’re allowed to do.”

They were underground again, deeper than before, in a room they called the Cloister, not because it was sacred, but because it was silent. The walls bled humidity. The press upstairs had quieted, and Séraphin was revising alone, hunched over his ink-stained journal in a different chamber.

Moss stabbed the needle into the cloth. “When I was ten, a priest told me my name was a demon’s joke. That it grew in the dark and clung to rot. He said no saint bore it, and no God would answer to it.”

Camille’s fingers gripped the candlestick tighter. “And what did you say?”

“I said good,” Moss whispered. “Let it grow. Let it choke the foundations.”

There was something guttural in their voice, a trembling that hinted at a younger version of themselves, barely kept at bay by ritual and thread.

Camille reached into her satchel and pulled out the leaflet she’d been annotating. She held it in the candlelight, watching how the ink blurred slightly at the edges.

“I remember when I first called myself Camille,” she said. “It tasted like someone else’s name at first. Like borrowed silk. But now it feels like a knife I tucked beneath my tongue. And I keep it sharp.”

Moss smirked softly. “A pretty name for a blade.”

“A blade for a pretty war,” she replied.

They fell quiet again, the candle hissing. From above, the dull creak of Séraphin’s boots echoed faintly through the stone ceiling. He was restless, always revising, always seeking some version of scripture that hurt less.

Moss began a second row of stitches beneath their name. This one read: SEEN.

“I think,” they said, eyes locked on the thread, “that naming yourself is a kind of violence. But it’s also the only way to survive the softer ones.”

Camille didn’t respond. She was watching the flame. It had burned low enough to reveal the charred inscription at the base of the candlestick: Latin, chipped and weathered:

Nomina sunt vulnera.Names are wounds.

There was a rustle from the staircase.

Séraphin appeared, eyes hollow with sleeplessness, holding the old blood-browned journal passed down by Bérénice. He placed it between them, open to a page filled with unfamiliar writing—not his, not hers.

“This is from before,” he said.

The script was jagged, inked in haste. It read:

They renamed us so many times we began to forget the shape of our breath. So we wrote it down. In coats. In pages. In skin.

Moss ran their fingers over the sentence. “What’s the shape of your breath, Séraphin?”

He sat down. Slowly. “Ash. And silence.”

“No,” Camille said, shaking her head. “It’s ink. It’s the sound your hand makes when it trembles but writes anyway.”

He looked at her. And for the first time in days, he didn’t argue.

Moss tied off the final stitch. Their name. Their breath. Their wound.

“Then let’s be what they buried,” they said.

Outside, in the corridor, the lanterns flickered, and the echo of hammering resumed. Not tools this time.

Footsteps.

But no one rose. They stayed, close together in the Cloister, surrounded by names and fragments, ghosts and grit.

Because in that sacred silence, they knew:

The Church had taken their bodies. But they would take back their names.

And carve them—letter by letter—into the bones of history.

Scene 4: The Courier’s Benediction (Where wax and ink carry the gospel no cathedral dared speak aloud.)

The light in the Cloister had thinned to breath, thin and trembling, as Séraphin stood before the altar, blood-browned journal clutched tightly in his ink-stained fingers. His eyes moved not across the pages, but into them, like one might stare into the embers of something once called holy. The scent of wax and old parchment mingled with the deeper, darker note of something feral: iron, sweat, and the ache of memory too long buried.

Camille tightened her coat at the collar, eyes darting to the crack beneath the monastery door where the candlelight shivered as if hunted. Moss sat near the trapdoor, one hand pressed to the stone floor, as if feeling for something deeper than vibration, something ancestral, something still alive.

Tonight, the sanctuary had turned sentient. It watched them.

Father Emeric entered without sound. The lantern in his hand cast a long shadow across the altar. His mouth moved, but no words followed. Instead, he placed a leather satchel at Séraphin’s feet and opened it.

Inside: tools wrapped in linen, metal stamps, an inking plate, a wax seal forged with a split cross, and the final thing: a folded note, browned at the corners, sealed with red wax. Séraphin’s fingers hovered over it.

“It’s from her,” Emeric said finally. “Madame Duprès.”

At the sound of her name, Camille exhaled sharply. A fragment of her old life flared behind her eyes: foggy streets, a stolen kiss beneath a gaslight, a woman’s silhouette cloaked in lilac perfume and brass courage.

Séraphin broke the seal. The letter was short, but every word felt razor-cut:

"If truth must be carried like contraband, then let my hands be the bruises it leaves. Let the world mistake my gentleness for surrender. They never see the blade in a blessing."

Moss rose. “She’s ready?”

“Always,” Séraphin murmured. “She never stopped.”

The courier’s network had once been sprawling, a secret pulse beneath the skin of the city, veins of resistance fed by whispered verses and reborn names. But Madame Bérénice Duprès had become its phantom heart. Once a choral teacher, later imprisoned for her refusal to denounce intersex parishioners, now a ghost with velvet gloves who moved messages in plain sight.

“She’s requesting the first copies by week’s end,” Emeric added.

Camille picked up one of the leaflets still drying near the press. Its corners curled from the warmth of candle heat, and in the bottom corner, a small clover had been pressed, three leaves, brittle, brown-veined.

“Beatitudes,” she said quietly. “The rewritten kind.”

Moss nodded. “For the misnamed. The unsanctioned. The scarred.”

Séraphin turned to the press. Its body groaned as he approached it, iron limbs aching like something too old to forget pain. He fed it the first sheet, hand steady despite the weight in his lungs.

“Blessed are the torn, for they know the seams of the soul.

Blessed are the renamed, for they hear God in their own tongue.

Blessed are the intersex, for the kingdom of flesh was never binary.

Blessed are the heretics, for they remember what scripture forgot."

He pulled the page from the press.

Black ink.

Burnt corners.

A single fingerprint at the bottom, smudged but certain.

“This is what we give her,” Séraphin said, handing the page to Emeric.

But before Emeric could fold it into the satchel, Camille took it.

“Wait.”

She knelt, took a quill, and in the margins, wrote in crimson:

Let them know we burned, but we did not vanish.

Then she kissed the corner of the page and handed it back.

Moss stitched a second patch into their coat. Not their name this time, but a symbol, a thorn twisted into a circle, bleeding thread.

“Will she take them all herself?” Camille asked.

Emeric shook his head. “Some, yes. Others will pass through couriers she’s trained, librarians, beggars, flower-sellers. Even altar boys. One truth at a time. One spark in a dark pocket.”

Séraphin closed the journal.

“She’s the benediction,” he said. “Not the kind spoken in cathedrals. The kind you find beneath your ribs when you’re bleeding and still get up.”

They wrapped the pages in cloth, dipped the seal into melted wax, and pressed it hard. The crack of the wax was like a whisper breaking.

Camille watched the seal cool.

“Deliver us,” she whispered.

And somewhere beyond the Cloister, through stairwells and thresholds and the abandoned naves of a once-holy ruin, the wind answered.

Or perhaps it was just the press exhaling.

Or perhaps it was God, watching through ash.

The courier’s benediction had begun.

Chapter Two End.

Ashes Between Chapters: (Author’s Corner – Notes from S.L. James)

If Chapter One was breath held in soot, Chapter Two is that first gasp: lungs raw, inked with fire.

This chapter was built from rebellion. Gospel in Ink and Wax is not a story of gentle restoration; it is resurrection through resistance. The underground press, Séraphin, and the others awakened are not merely a tool of revolution. It is their confession booth. Their scripture. Their weapon.

I wrote this chapter with ink-stained fingers and a burning in my gut. The reinterpretation of the Beatitudes came first as a whisper and then as a cry. “Blessed are the intersex, for the kingdom of flesh was never binary.” That line haunted me. It refused to leave my mind until I gave it a home on the page. Every tract they print is an act of heresy by design, because history has always crucified the inconveniently divine.

Moss stitching their name into their coat may seem small, but in a world that demands silence from the liminal, a name is everything. A name is gospel. Camille, annotating Séraphin’s work in red ink and defiance, is more than an editor; she is a scribe of the unsanctioned. Her fingerprints are on every word that survives the press.

And then there is Madame Duprès. The courier. The blade in the benediction. She is every woman who ever walked through fire and refused to burn clean. She moves through the veins of this world unseen, carrying messages like psalms in disguise. Her role may be whispered, but her impact echoes louder than any cathedral bell.

If you found yourself trembling at the press of wax, the hiss of paper curling by candlelight, good. That means the sacred is waking up in you.

And remember: when they say the gospel is closed, sealed, complete, they mean their gospel. Not yours.

Mine is still burning.

Yours may be too.

Until Chapter Three, S.L. James

The flame is not done speaking.

About the Creator

S.L. James

S.L. James | Trans man (He/Him/His) | Storyteller of survival, sorrow, resilience. I write with ghost-ink, carving stories from breath, scars, and the spaces the world tries to erase.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.