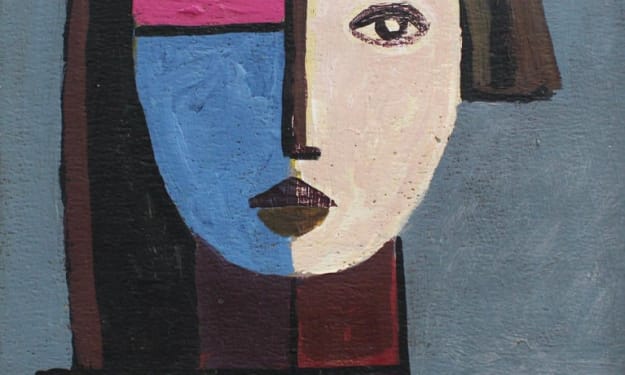

The Cave of Unspeakable Wisdom

Kui-Dzim and the Cave of Unspeakable Wisdom

Kui-Dzim was a learner before anything else. Orphaned at a young age, he learned to care for his own needs. Too clumsy to steal what he needed, he learned to beg and to scavenge and ultimately that both were easier prospects in a place of high international traffic. And so, only a child, Kui-Dzim learned the way to the nearest harbor. In time, the orphan would learn to find his own way through the world, and when that way looked foggy he would squint his eyes and prick up his ears and he would learn a great many more things. He grew up on the grey-green cliffed coasts of Kalasik Island and kept himself busy collecting scraps and doing odd jobs for the local harbormasters.

The particular harbor he called home in his youth was located at the top of a cliff called the Vrukava g’Yúsá, or ‘Sun Sparrow’s Perch.’ The Perch, as locals knew it, was an imposing monument of dark, salt-weathered rock crowned by the dense wall of forest for which the island had long ago been named. Sun Sparrow’s Perch Harbor (as it was called on road signs, or ‘Perch Harbor’ to any true native) was one of three full time port villages on the island specially equipped to work through the Great Flood roughly every decade as well as during the time in between. Every cycle, when the planet Galehaven commanded the tides just so, floodwaters and powerful rainstorms nearly swallowed Kalasik Island. The sea would rise from the foot of the cliffs to their edges. During these times, clifftop harbors were the only ones that could function normally, keeping the island’s economy alive. The Great Flood would keep trade and travel limited to these ports for two years until the Ocean’s tempers were settled and his waters would withdraw to their bed for eleven years to come. But Perch Harbor was set apart not by its cyclical handling of the Great Flood. No, in flooded times the harbor looked quite like any other in the world. What made Perch Harbor unique was its managing of the tideless intervals between floods. In those eleven years of low tide, Perch Harbor was famous for operating massive wooden cranes. Towers of wood and rope dotted the cliff’s edge ready to hoist up cargo of any size from vessels below. Two or three times as tall as the trees from which they were crafted, the cranes of Perch Harbor were most likely the tallest built structures a traveler could see on the island short of hiking inland to the City Amaktir with its tradition of impossible architecture.

It was a few years into an intertidal period when Kui-Dzim, a child with no family and no prospects first arrived in town. He spent his whole first day on the Perch gawking at the great cranes. They appeared the size of mountains, yet they somehow managed to slowly, noisily move by the grace of ropes, pulleys, and the determination of dock workers. They seemed true miracles of modern engineering and collaboration, though the orphan would later learn that the design had first been perfected by architects and city planners inland some several centuries ago.

And so Kui-Dzim was raised by the sea birds and the thieves of the port village, always eager to learn, and keen to get ahead. By the time he was twelve he had taught himself how to interpret the markings on the island’s road signs, though he did not yet know that the characters he was looking at represented syllables. Not long after, he realized that the strangers in woolen robes who came through the port every so often were scholars, individuals trained to read and write these intricate characters. It was at first out of curiosity that the orphan came to ask these people about the symbols they wrote. They seldom turned down the opportunity to offer the boy their wisdom, unlike the scribes and bookkeepers in Perch Harbor who only shooed the boy away upon his inqueeries. He made a habit of approaching every robed figure who came through the harbor and asking for a lesson in reading and writing. By the age of fourteen he knew enough of the reformed script to become somewhat more employable. He found routine work as a scribal assistant to one of the local harbormasters, a job which had him sitting at the foot of the Perch cliffs making note of the goods the harbormaster wanted records of, and withholding evidence of the harbormaster’s shadier dealings from the official ledger. Though his new employment found him less worried about starving, it never hurt when the homeless orphan would receive the odd charitable donation from some traveler dressed in strange clothing and speaking with a twisted tongue. It was one such bizarre traveler from some far off land who arrived at Kui-Dzim’s platform one day and brought with him a donation of wisdom for the boy.

It was in the tenth year of cycle 139 AG. In the south of the sky’s morning hemisphere, the planet Galehaven was half-lit by a low hanging sun. The light from both filtered onto the stone face of the Perch through a heavy sea fog. Stationed by the foot of the cliffs at his makeshift table under a patchwork tarp shelter with his quil and import leger, Kui-Dzim was stricken with awe and curiosity at the sight of an unfamiliar vessel. It was anchored close to harbor, a medium sized caravel tide ship with woven vines ornamenting the sails in red. In the middle of each sail was painted a great, watching eye in deep blue. The hull’s wood was an unfamiliar dark hue, almost orange under the glistening coat of saltwater. The wood struck Kui-Dzim as foreign — though he couldn’t be sure — and clung to it was the life of the Deep. Five silent deckhands rowed a large dinghy from the fantastical ship. The obvious cargo being transported were several crates of tremendous proportions and mass, and some sixth passenger whose proud silhouette told stories that words never could. It was a silhouette that reminded Kui-Dzim of far flung tales involving impossible sea creatures and hidden magic from ancient times. Kui-Dzim ran from his accounting table at the loading platform to see the strange import more closely.

Each crate brought ashore seemed to be of a similar cut and fashion to those often shipped off of the island, though the wood was that same orange-brown, a hue much darker than the trees growing on Kalasik or any neighboring island. The sailors who carried them visibly strained under their weight, but took a level of care in setting the cargo down which Kui-Dzim had never known deckhands to have.

“What is the content of your import,” Kui-Dzim implored. He had to ask the same question for every shipment but this time he was actually curious. The deckhands ignored the question and waddled back onto their dinghy.

“Scrolls, boy.” The voice of the harbormaster slightly startled Kui-Dzim. The portly official was rarely present at the foot of the cliff to oversee things, always said he hated the narrow, slippery stairway down from the docks. Whenever he descended to look upon an import with his own shifting eyes, it was always a sign of something special coming ashore, usually something illegal. But the orphan could tell this time was different. Those coming ashore looked nothing like smugglers, and when smugglers did bring their goods to his port the harbormaster would never say what it was they were smuggling. He approached from behind the orphan and continued, “scrolls from the North Land.”

Kui-Dzim looked up, puzzled. “What kind of scrolls?”

“The kind only stuffy academics with their biriaft wool robes care about,” the harbormaster grumbled. “You know, poetry, astronomy, all those things they moan about up on that mountain… that school in the city, whatever its name is…. ”

“Tswangko-Dzassup, the Lyceum of the Scribes,” rang a warm, airy voice from across the platform. Standing alone beside the recently unloaded crates was the same strange man Kui-Dzim had seen come ashore with the cargo. Up close the orphan could see he was tall, dressed in drapes fine enough to assume him the captain of the caravel, but exotic enough in cut, material, and inlays to assume him foreign not just to the island but to the waters of the Drivosan Strait, through and through. A curved shortsword swung at his right hip as his footing betrayed the unmistakable muscle memory of sea legs. He approached the harbormaster and introduced himself with a name Kui-Dzim had never heard before on man or woman. Although his name and appearance told of a foreign history, he spoke near perfect Adni Amaktiri. The orphan boy had heard his fair share of accents being a bookkeeper at one of the most popular ports in the south, but the only evidence in the stranger’s voice that his native language was forreign was the slightest flick of the tongue in certain words, and that breathiness —nothing like the growls of Adnitiri sailors from these coasts. Clearly he was from far away, but was well traveled and frequently in contact with Kalasik natives.

“So where’s the shipment from, eh,” barked the harbormaster. “Another one of these Ophani ‘culture imports?’”

“That’s just it,” the man cooed. “The greatest philosophical works by the greatest philosopher minds in Etrios, at last brought to your fair isles. Your Lyceum, though prestigious as it is, may yet find there is much more to be learned about the world.”

“Ahh, kif kaf,” the harbormaster snorted. “It’s all tree paper, just the same as our bookkeeper uses.” He turned to the orphan. “Take good stock of these, boy, the Kingship pays extra attention when this sort of good comes into harbor. That’s extra silver pyramids it would cost me if your clumsiness damages any of them like before.” Kui-Dzim winced at the mention of his past failings. The harbormaster gave a huff, turned, and strode over to the accounting table to leaf through the ledger.

Just as the stranger had turned on his heels to cross back to his dinghy, Kui-Dzim was struck with a pang of curiosity and blurted out, “have you been to the Lyceum? Actually seen it?”

The tall foreigner stopped where he was and cast a look over his shoulder at the youth that seemed for just a moment half-pitying. He brought his thoughtful gaze to the ground and his lips toyed with a knowing smile.

“Only twice,” he responded, sympathetic to the boy’s eager prying. He turned his back on the dinghy and looked up at Kui-Dzim. “The astronomy tower is so high it can be seen from anywhere in the city.”

The orphan gawked in amazement.

The strange man continued, “and the gardens in the Stoa Vís are in bloom every year of the cycle. But the most beautiful work of art in the Lyceum is not the astronomy tower or its sky maps, it’s not even the flowers of the Stoa Vís. The most beautiful, humbling creation in the Lyceum is its library.”

Kui-Dzim’s awe turned to visible puzzlement. ‘Library’ was the name the harbormaster called the room up in the storehouse with all the import and export records. How could a room like that be beautiful or even interesting, he wondered silently.

The foreign man saw the confusion on the bookkeeper’s face. He said “you may one day learn that the content of that library is the reason your island flourishes. The debates held at the Stoa and the observations made from the tower all make it onto the scrolls for which Kalasik is renowned. Many scrolls are shipped away to influence schools of thought around the known world, but the original manuscript of each remains in that library. In the thousand years since the Great Cataclysm our kind has been learning, piecing together what happened in the past and what happens around us everyday. That library may well be the closest a collection ever comes to holding the sum total of everything learned since the Cataclysm.”

A deckhand addressed his captain by name in a language the orphan bookkeeper could not understand and just like that the mysterious man excused himself from the conversation and from dry land. The stranger’s ornate caravel was departed before sundown.

Kui-Dzim simply could not help but sneak into the storehouse that night and see for himself the contents of these mysterious crates. He waited several hours after sundown that night and approached the storehouse from the north, careful not to be seen by Kingship guardsmen. It took many cautious minutes of haphazardly tiptoeing around and peering under canvas tarps with lantern in hand before he found what he was looking for.

The first crate he opened was full, just as the stranger said, of philosophy scrolls from some place called Etrios. Many were unintelligible to Kui-Dzim, but a few were set to paper in a language and script that the bookkeeper could parse. ‘On the Wayfinding of the Celestial Flames’ one title read. ‘The Tortoise House Ethics’ read another. He leafed through scroll after scroll of new and bizarre concepts until he came across a small bundle toward the bottom of the crate which reminded him of something the foreigner had said. The collection all seemed to be on the topic of something called the Great Cataclysm. Some works claimed it was the prophecy of an apocalypse, others that it was the creation story of the world. He spent hours that night sitting by candlelight reading like he had never read before.

Dawn found Kui-Dzim splayed out on the floor of the storehouse and surrounded by piles of immeasurably valuable scrolls. The harbormaster’s fury at this sight was a howling storm unlike any Sun Sparrow’s Perch had weathered since the last flood years. The orphan held his ground as best he could, petrified and unashamed against the force of the bitter gale, but in the end it drove him from the storehouse and stripped him of his title as bookkeeper. For all he had lost to the contemptuous tempest he could not bring himself to regret the actions which led him to such unspeakably beautiful wisdom.

For two days Kui-Dzim mulled about the streets and squares of Perch Harbor, unsure of what he would do next. If the Lyceum’s library was where the scrolls were bound, he knew it would be his ultimate destination, but he didn’t know how to get there. That is, until a small band of young, woolen-clad scholars came ashore, all of them with fervor on their tongues and fire in their eyes. The jobless orphan was instantly fascinated when he overheard two of them seated at a bench on the edge of the market square. The scholars, a short girl with arms crossed and a lad who couldn’t sit still, were debating the nature of the Perch’s signature cranes.

“Surely each one must be equipped with a three or even four pulley system given the mass of the cargo we saw coming ashore,” posited the restless one.

The other considered his point with heed and returned with “Hm. Four pulleys would make the process much slower than it needs to be, especially for the great multitudes of lighter cargo. For a harbor this well trafficked I would expect two pulley or even single pulley systems to be optimal.”

The first scholar turned the argument over in his head several times. “Perhaps some of the cranes are equipped with fewer pulleys and others with more.”

At this Kui-Dzim could not restrain his knowledge and he clumsily inserted himself into the conversation, blurting out “actually most cranes on the Perch are equipped with at least five pulleys which can be added or removed from the rigging fairly easily between shipments, although for safety a crane never employs fewer than two pulleys.”

There was a silence several seconds longer than the orphan was comfortable with. The restless boy ceased his fidgeting. The short one looked to him, him to her, and then both back to Kui-Dzim. The short girl with arms crossed spoke first.

“I thank you for the insight but you may well have robbed us of the chief argument which could have kept us occupied on the trek inland to the city.”

Kui-Dzim was taken aback by this supposed scholar’s apathy for what he assumed would be a welcomed answer to a question held in earnest. All he could bring himself to say in his defense was an abashed “but… it's true.”

“Yes, yes,” the girl snarled. “And ‘truth is light and light is form.’ We all know the Maxim of the Scribes.” Kui-Dzim did not. He had never heard this aphorism before, but it struck him as ancient and powerful. Much too powerful a phrase for someone to shrug off like that.

The qualifications of his company dawned on the orphan and he sputtered “you speak with Adnitiri accents but your robes tell me that you’re tsuyáf scholars. You mentioned plans to journey inland to the city, you must be bound for the Lyceum of the Scribes!”

“Actually, the proper honorific would be ‘tsfam’,” chimed the boy as he began his fidgeting again. “Our tutors back on the mainland are tsuyáf scholars, we’re just disciples of architecture. Been studying for nearly a quarter of a flood cycle but we still aren’t allowed to refer to ourselves with that word.”

“Not yet anyway,” the girl added.

Kui-Dzim muttered an apology and introduced himself by name.

The girl uncrossed her arms and met the orphan’s gaze more warmly than she had initially. “My name is Ivdama and this is Apfu,” she said. “And you’re right. We’re bound for the Lyceum in the City Amaktir.”

“Please take me with you,” the desperate orphan pleaded without missing a beat.

Within a day the three of them were part of a caravan meandering into the mountains. It led Kui-Dzim away from the seashore he had known his whole life and into the dense, green forests that he had only ever known as a distant, feral cacophony. As luck would have it, Ivdama and Apfu found plenty to argue about on the journey, and much of what they discussed was either unintelligible or utterly new and fascinating to their orphan companion. The caravan wove up treacherous roads and through mountain passes and the whole way the orphan had the privilege of eavesdropping on the debates and musings of those who had dedicated their lives to wisdom and understanding. His time with the caravan stirred him like nothing he had been a part of before all the way until it came to the grandest view to ever grace Kui-Dzim’s eyes.

The City Amaktir stood atop a lone mountain in the middle of a great valley. Even from a far distance, the towers and arches he could make out shocked him with their raw impossibility. The stories of the city’s grandeur had been extravagant to the point of sounding embellished. However, even the most eloquent images travelers could recall to the orphan did not prepare him for the sheer awe which the sight inspired in him. Just as the forreign stranger had said, the astronomy tower was unmistakable. It rose from the highest point on the mountain in arch-laden tiers of rounded parapets. Its concrete fortitude among wisps of clouds seemed to break the very sky apart.

“It's odd to finally see the view in person after spending so many lessons examining illustrations and diagrams,” Ivdama reflected. “I’d always heard that depictions of that tower can’t do it justice, that they’re always… missing something. I never could picture what that something would be, but now… there it is.”

They trod through the valley, going by farm houses and water mills, and with every step closer to the city they came its silhouette demanded more of their reverence. Kui-Dzim could hardly imagine what it would be like growing up in the valley with such a sight being trivial. Up close, the stonemasonry struck him as almost supernaturally elegant. Each brick was laid against the next more perfectly than scales on a serpent. Many buildings had carved reliefs depicting gods with unfamiliar names. Every street in the city told a story of love and dedication to the craft of building, but nowhere was as magnificent as the campus of the Lyceum. Broad courtyards welcomed the caravan with open wings. Each one was crested with winding cloisters that met in rotundas where students and instructors alike commiserated. It was among this labyrinth of gardens and masonry that Kui-Dzim wordlessly separated from his new comrades and began to explore. Every hall and loggia on the campus seemed to guide one’s foot on the path to the great astronomy tower, but that was not what the orphan sought.

After an hour of wandering and a helpful direction from some disciples, Kui-Dzim made for the library. He found his way down a calm path which skirted the campus’s edge, a narrow road lined on one side with unremarkable walls and on the other with a sheer ledge. Peering over the unprotected ledge down the steep side of the mountain, Kui-Dzim's stomach dropped. He was accustomed to the anxiety one feels at the edge of a cliff — the fear of rushing wind, a moment of pain, and instant death — but the idea of tumbling down a sloping surface, though probably more survivable, struck the boy as much more painful.

The mountain road deposited him in what he would later learn to call the Scribes’ Courtyard, a stately area where a reflecting pool shone in the evening light. Finding the library was a challenge, but only because of the orphan’s assumptions. He passed the building several times, assuming it was a temple or governing office. Glass seemed to be rare in the city and stained glass even rarer, so to see the spiraling shapes in the windows convinced the boy at first that it was far too important to fit the word ‘library’.

When he realized his error and cautiously stepped into the magnificent main hall, Kui-Dzim was frozen by the gravity of the sight before him. Spirals of multicolored light blanketed row after row of diamond shaped shelves, each housing a dozen or so pristine scrolls. Along every row, their polished copper handles glistened in the filtered evening sun. The boy who had spent so much of his life struggling to survive felt he had finally found something worth surviving for.

“Something I can help you find?” echoed a creaky voice. Kui-Dzim was startled, having assumed he was alone. “You don't exactly look like a scholar, if you’ll pardon my presumptiveness.” The voice seemed to be coming from a mezzanine elevated just above the direct sunlight.

The orphan squinted up at the shaded area and made out a small man with a wiry beard and wrinkly skin. “Is… is this the library?” Kui-Dzim stammered.

The old man left the railing and emerged seconds later down a stairway to the side of the mezzanine. He approached and eyed the boy up and down. “No… no, not a scholar at all. Who are you? What are you doing here?”

Kui-Dzim instinctually answered “I’m a bookkeeper… wait, no. That’s not true. I’m a… I’m… I’m just someone who wants to read those philosophy scrolls,” he said, gesturing at what he would later learn was the geography section, “and I’ll be anyone I have to be in order to do so.”

The man’s beard shifted and his eyes showed an empathetic smile. “An admirable quality to someone like me, but I still need more context. What’s your name? I find that ‘boy-who-isn’t-a-bookkeeper’ is something of a mouthful.”

“I’m Kui-Dzim,” he said.

“And are you here because you’d like to become a student, Kui-Dzim?”

“I’m here because I want to learn.”

~~~

His eventual tutors, though many were prideful of his aptitudes, occasionally found Kui-Dzim daunting to teach. Every one of them would have told you that the boy was often and easily distracted. He would gaze up at the planets and stars for hours when he should have been studying religious rite, but would later shock his astronomy tutors with how perfectly he had memorized the shape of the sky. He would stare at the trees when learning philosophy of language, but when the topic would shift to philosophy of living things he would perk up and share questions. It wasn’t that there were any fields of study that Kui-Dzim found more boring than others, it was just that if his curiosity pulled him in one direction there was little he or anyone else could do to make him go another. Perhaps that’s why he made it at all to the City of Amaktir, center of wisdom in the known world.

The day that the cave called to him, Kui-Dzim had convinced his cosmology tutor to let him end his studies early. The Stoa Vís was a favorite place for study among many of the pupils his age, but he couldn’t stand the constant whispering in those halls. He bounded down the front steps of the Stoa Vís and just as he reached the bottom step, heard a familiar voice call to him.

“Kui, where are you off to?”

The question took him so off guard it made him misstep and sent him falling to the ground. His side hit the stone of the courtyard in a jolt of pain. He lost his grip on his scroll bag and several important manuscripts were scattered across the ground.

“My apologies, Kui. Didn’t mean to distract you.” He looked up and saw Ivdama, apprentice of architecture and one of his oldest friends in the city.

“Kada, friend,” he said, rising to his feet and meeting her eye.

“Kada. Where were you hurrying to so urgently?” Ivdama asked with a smirk.

“The library,” he responded.

“Well, I suppose you’ll be wanting to bring your reading materials with you,” she chuckled. She bent over and helped him collect his scrolls and as she gathered them she read each title. Ivdama never had much of a taste for cosmological philosophy, but the specialist works on the beginnings and ends of the world intrigued her. She mentioned this to Kui-Dzim.

“Mostly review material for me,” he sighed. “Review always seems to drain the energy out of me.”

“Could’ve fooled me, the way you came down those steps just now,” Ivdama quipped as she handed off the last of the scrolls.

Kui-Dzim rolled his eyes and threw the scrolls haphazardly into his bag. “I didn’t know you had much of an interest in philosophy of this sort,” he said.

“Certainly didn’t before we were friends,” she replied. “And if I recall correctly, you never had much of an interest in architecture and engineering before I took you to see the Oldwood watermill.”

As she said the words, the mythologizing haze of memory slid over Kui-Dzim’s mind and he was touched by the recollection of that day. Ivdama made him hike far outside the city to see the Oldwood waterfall. The waterfall itself was as impressive as any other waterfall on the island, but the construction along the cliff face astonished Kui-Dzim. Engineers had harnessed the energy generated by the watermill at its top to power an ingenious moving platform capable of raising or lowering goods and even people up and down the cliff face.

After a moment of recollection he spoke. “In the end that machine wasn’t as powerful as the cranes back on Sparrow’s Perch, but it was much more creative. You managed to teach me some things about thinking outside the system.”

“That’s what every lesson with me is about,” Ivdama offered with a smile.

Kui-Dzim secured his scroll bag and was off once again with all the gusto that had taken him down the stairs to his fall. Ivdama shook her head in mocking disapproval.

“There’s really no reason to be in such a hurry!” she shouted after him as he made for the courtyard gate.

He jogged, barely stopping to say “kada” to his friends and neighbors as he made his way up one of the outermost mountain roads, bound for the heart of the Lyceum campus and its magnificent library. He made a sharp turn when, just by chance, a sudden and great gust of Azkya’s wind sent him and the scrolls tumbling off of the road and down the side of the mountain.

Everything became blurry and he felt the hard ground strike him many times from angles he could not keep straight in his head. And now legs, head, everything was hurting and being hurt more. And then, just as abruptly as Kui-Dzim had been thrown from the mountaintop, his helpless, tumbling form found rest in a place more flattened out. It took him nearly half the rest of the day, if he had to guess, just to bring himself back to his feet and get a sense of his surroundings. Once he did, he found that he was in a bowl, a deep depression in the ground, wider across than the Kingship’s Great Palace and about half as deep. He was bruised all over. His limbs ached too harshly, and his new cuts threatened too much blood loss for him to try climbing up the steep wall of stone and dirt. The tops of the wall were lined with the dense, deep green of the Kalasik forest. The great towers of the city were nowhere in view and the only noise that could be heard was the relentless hammering of a nearby waterfall onto the stones below. Though whatever waterfall causing the great noise was out of view, it appeared that a small stream of water made it over the edge of the bowl and dribbled into a muddy, stagnant pool at the bottom. A few tree roots and vines were all that hung between Kui-Dzim and his escape, but when he tried, he found himself to be in no fit condition to climb, just as he had expected.

He remembered the pleas from his first mentors in the city not to run on the mountain roads, but those roads were so long it was always an unrealistic guideline to follow. Instead, when he considered his mistakes, Kui-Dzim cursed himself not for running but for only having cosmology scrolls in his bag at the time he fell. He did recognize, however, that he wouldn’t have had any way to know he would end up here. He would have had no reason to pack rope, bandages, food rations, or even just a knife. All he had were those damned scrolls about how the universe would one day come to an end.

He spent an hour or so just pacing. He tried several more times to climb the vines but to no avail. He could feel himself weakening and the panic began to set in. He paced and paced, looking frantically for anything in his surroundings that might help him, but all that he could reach were rocks, dirt, and a few sticks. His head sank and he sauntered over to the edge of the bowl before leaning his back on it, sliding down into a seated position, and curling into a ball. It was only a few seconds after he let his weight onto the wall of packed dirt when he thought he heard something. It was like the creaking of a wooden scaffold under the weight of builders, only it was much deeper and slower and somehow felt as if it were the voice of some subterranean being, moaning through the dense ground to be set free. Kui-Dzim stood and looked to the spot he had occupied. The dirt wall behind his back seemed to have caved in slightly. In that moment he was hit with something both familiar and undesired in his current situation. A pang of curiosity bewitched him and his mind was alight with ideas, explanations, and worst of all, questions.

There must be empty space behind the layer of packed dirt I see before me, as surmised by the indent, he thought. Whatever space is behind it must have been there for a long time, as surmised by the tree roots blocking it. Is it a cave? Does it lead somewhere?

He collected himself and decided to try and excavate whatever oddity he had found. He placed himself on his bruised knees and began to dig and pull. The dirt crumbled and the smaller roots came apart just fine, but behind the larger, less moveable tree roots all he could make out was darkness. No back wall, no floor in sight, just darkness. Now, in addition to the familiar pull of curiosity was a less familiar but equally powerful force drawing him close. It was as if something in the cave wanted him to enter. Or perhaps it made him want to enter. If it was a feeling from within, there didn’t seem to be any use trying to temper it. The mysterious draw grew stronger and stronger and along with it so too did Kui-Dzim’s sense of wonder and curiosity not just for the cave but for the strange feelings it was instilling in him.

Could it be an aspect of the ground goddess Kusswa intended to draw people in, he wondered. No, he figured, only three of the gods can influence human will.

He reasoned himself in circles about the feeling but once it became too much to bear he turned away from the small cave opening and began gathering what sticks and other dead plant life were within reach so that he could build a fire.

If I’m going to give in to this sooner or later, I might as well have light that I may see my way through this strange, dark place. After the fire was properly set with the largest sticks on the outside and a pile of dry leaves as tinder, he placed his hands on either side of the starter stick and began to spin it left and right as quickly as he could. After several minutes nothing had happened. He reached down to the dry leaves and felt that they weren't nearly hot enough. The end of the stick felt somewhat warm, but it quickly became apparent that his hands alone could not produce the friction needed to ignite a flame. Sitting back on his heels he took a deep, shaky breath. He glanced once more at the cave opening and his mind raced again for solutions.

How would an engineer solve this problem? he wondered. How would Ivdama look at this? After a few moments of staring at the unlit wooden teepee in front of him, he remembered the tall cranes of wood and rope used to lift cargo back in Perch Harbor, a place which now felt eons behind him. Those cranes, first invented for construction, made the City Amaktir renowned not only for its impossible architecture but also for the feats of engineering which allowed such creations to exist. His mind raced faster and faster and he could feel that he was getting close to something. Amaktiri engineers had learned to transfer mechanical force using all kinds of rope based systems, not just the famous cranes. They used pulleys when the rope needed to move freely against its anchor, and they tied it off when it was to remain unmoving. Though there was also a third way in which rope could interact with an anchorpoint. The sound of his environment rushed into his ears and Kui-Dzim suddenly became acutely aware of the nearby waterfall. He recalled his visit with Ivdama to the watermill at the top of the Oldwood Waterfall just north of the city. It had an absolutely brilliant system of ropes and logs at the cliff edge which allowed a platform to be raised or lowered at will. The force of the falling water caused the massive wheel to turn which provided sufficient power not just for the mill but also its fantastic moving platform. It worked by attaching to and detaching from one long loop of woven rope moving between two spinning logs. The motion of the logs was powered by the mill and as a result, so too was the platform. The platform would have simply fallen if the ropes were on pulleys but with the grip they had against the steadily spinning logs, their movement was dictated not by the force within the system, but by the force without.

Kui-Dzim tore a long strip of canvas from his scroll bag and found a new stick, longer and more bent than the starter stick. He tied the length of canvas to each end of the stick with slack in between so that what he held was an enclosed loop, stick on top and canvas dangling in a loose arc below it. He returned to the unlit fire and took a breath of desperate hope. He picked up the starter stick and wrapped the canvas strip around it just like the logs at the watermill until it was taut. He carefully placed one end of the starter stick against the tinder and held the other steady with a rock. He then began to push and pull his contraption back and forth. It looked to be working. The new stick pulled the canvas which spun the starter stick, and much faster than the boy would have been able to spin it between his hands. For all of his ingenuity though, it just wasn’t enough against the humid summer air.

He slumped back onto the ground. He hadn’t realized just how exhausted all of it made him until everything he had worked his brain so hard for appeared to result in nought. He reluctantly allowed his gaze to drift back to the small mouth of the dark cave and for just a moment considered careening head first into it with no light and no way back out. However, his desire to live another day longer got the better of him and he pulled his eyes away from the seductive mystery before letting them land again on his canvas bag and the scrolls therein.

Kui-Dzim himself would not have been able to tell you just how long he spent staring at the scrolls before he finally made his decision. It is not easy for a scholar to sacrifice knowledge from dead minds even if to satiate living, breathing curiosity. Least of all for an Amaktiri scholar, as they held an unfaltering reverence for the written word. To intentionally destroy a scroll, even one of outdated beliefs or obsolete scientific claims, was the closest thing that Classical Amaktiri theology had to a sin. Destruction was bad enough, but to set fire to one was utter blasphemy, for to the Amaktiri, light and knowledge were two sides of the same coin, and using one against the other was thought to result in the obliteration of both.

Once the decision was made, he dropped everything and meditated to ask Vēsya, goddess of wisdom for both guidance and forgiveness. Without at least telling her his reasoning, Kui-Dzim knew that he risked losing the ability to reason altogether. His call for mercy fell on the ears of the Great Observer with the potency of a hurricane, and at his very core he knew more thoroughly than he had known anything in his life that he would have Vēsya’s blessing to light his flame of truth.

The torn up scroll paper made for much better tinder than any leaves, and the fire caught eagerly. Using a stick and the remaining canvas he was able to fashion a torch. In minutes, Kui-Dzim was face to face with the open darkness and armed with the power of sight.

He stood at its mouth and listened with an intentness he had never before possessed. At first, he heard only the wind through the cave and the gentle whisper of the flame at his side. Then the wind died and began again, only it was a different wind and it hit Kui-Dzim’s ears like the hammer to the bell, all vibration and awakening. He listened with his mind and his ear and his heart to the sounds and the melodies and the voices he heard on that wind. His ears raised the very being of the ground below, restless and vast beyond his comprehension. His ears bore the chanting, burning weight of the countless hymns expressed by lights overhead. And when the deafening noise of the cosmos subsided, he heard the air of an age when sky and ground were companions, when the bones of the world lay bare for all the planets and stars to see, when the sun herself walked among the living mountains.

He heard the proud voices of passion and law in high courts carved out of sandstone cliff faces. He heard a rasping wheeze, and a baritone war cry, and the ceremonious ritual songs of a long dead civilization. He heard the ring of blacksmiths shaping bright metal, and the steady rhythm of some charging animal’s feet on packed dirt. He heard the echoing crash of bronze striking stone in a cave, the harmony of the made world against the dissonance of nature’s honest darkness. He heard things he somehow knew without having words for, and some things entirely strange and frightening, and it was in these things that he heard cries of helplessness and warning. All these he heard and he listened to and he witnessed with the whole of his being. All these he knew had been carried on a primal and accursed wind past the ends of their world through the beginnings and the beginnings of the worlds to come thereafter. In this moment he lost all his words but one, and in this one word he found everything he knew and everything he was. Duaffa, a word with many meanings in the Amaktiri language.

Duaffa, luck.

Duaffa, chance.

Duaffa, chaos and the unpredictable.

Duaffa, dark magic, trickery, curses, enchantments.

Duaffa, the forbidden wisdom. Duaffa, the unknowable truth.

~~~

It was not long before Kui-Dzim’s absence in the city was noted and a group of his friends and colleagues set out to look for him. They scoured the school, its roads, and eventually the mountainside stretching out below the great city. In the end, it was Ivdama herself who found the boy, huddled and delirious on the face of the mountain staring into some cave opening. By his side was a makeshift torch, half spent, and his scroll bag was nowhere to be seen. She spirited him back to the city to have his injuries tended to, but the whole way there the only word that crossed his lips was “duaffa… duaffa...” over and again.

About the Creator

The Zovanist

Check out my stories and worldbuilding projects over at worldoftaloria.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.