The Book That Changed My Village

A Journey Through Pages and Hearts

In the small village of Shonapur, tucked away in the lush green heart of Bangladesh, life moved slowly. The days were marked by the rhythm of the rice fields, the call of the muezzin, and the chatter of neighbors by the riverbank. I was twelve, a skinny boy with big dreams and a bigger appetite for stories. My name was Arif, and my world was limited to the dusty paths of Shonapur—until a worn-out book found its way into my hands and changed everything.

It was a humid afternoon, the kind where the air clung to your skin like a second shirt. I was sprawled under the mango tree behind our house, dodging chores, when my cousin Salma came running. She was sixteen, sharp as a tack, and the only person in our village who’d ever been to the city library. In her hands was a tattered paperback, its cover faded but the title still bold: To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee. “Arif,” she said, her eyes gleaming, “this book will make you think.”

I wasn’t much of a reader then. Schoolbooks were dull, and the only stories I loved were the ones my grandmother told—tales of djinns and brave princes. But Salma’s excitement was contagious, so I took the book, its pages yellowed and smelling of old paper. That night, by the flickering light of a kerosene lamp, I started reading. Scout Finch’s voice pulled me in like a friend sharing a secret. Her small-town life felt strangely familiar, even though it was set worlds away in Alabama. The way she saw her world—through curious, honest eyes—made me look at Shonapur differently.

The book wasn’t just a story; it was a mirror. Scout’s questions about fairness and kindness echoed in my head as I watched our village. Shonapur wasn’t perfect. There was old man Rahim, shunned because he’d married outside our faith. There were whispers about Amina, a widow who worked as a maid and was judged for it. I’d never thought much about these things before, but To Kill a Mockingbird made me wonder: why did we treat people differently? Why did some folks get to decide who belonged?

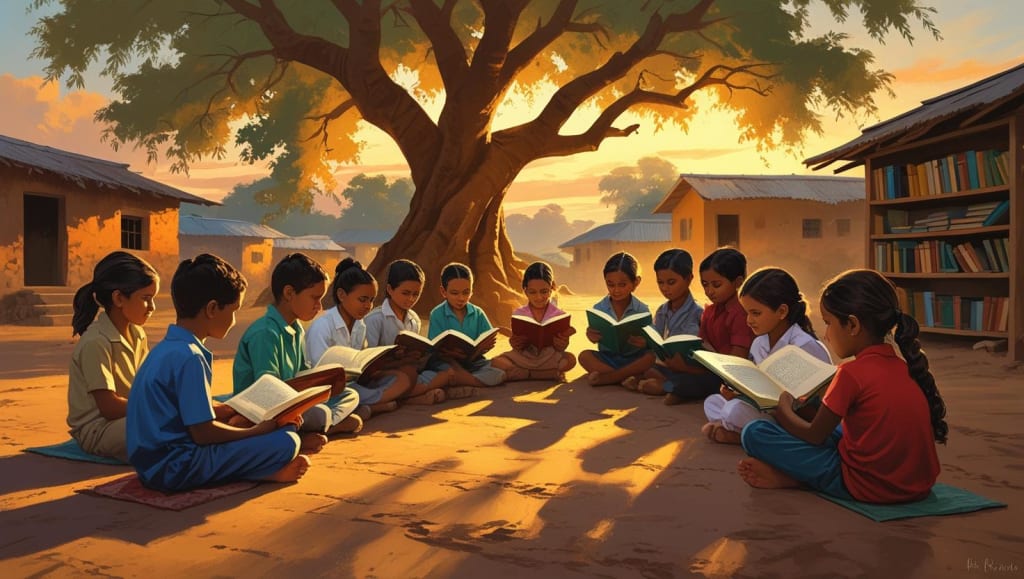

I couldn’t keep the book to myself. I read passages aloud to my friends—Raju, who dreamed of being a cricketer, and Farida, who was shy but loved to draw. We sat under the mango tree, passing the book around, arguing about Atticus Finch and what it meant to do the right thing. Raju thought Atticus was a hero for defending Tom Robinson; Farida said Scout was braver for asking questions no one else would. The book sparked something in us, a need to talk about things we’d always ignored.

Word spread. Soon, other kids joined our little reading circle. Salma, who’d started it all, brought more books from the city, but To Kill a Mockingbird remained our favorite. We started calling ourselves “The Finch Club,” a silly name that felt important. Our meetings weren’t just about the book anymore; they were about Shonapur. We talked about Rahim, who sat alone at the tea stall, and Amina, who worked so hard but was rarely smiled at. The book gave us courage to ask why things were the way they were.

One evening, during a particularly heated discussion, Farida suggested we do something. “Atticus didn’t just talk,” she said, her voice soft but firm. “He acted.” That’s when the idea hit us: we’d start a village library. Not a fancy one, just a place where anyone could borrow books and talk about them. We didn’t have money or a building, but we had the book and each other.

We went to Master Jalil, our schoolteacher, who had a reputation for being strict but fair. He listened as we stumbled through our plan, clutching the battered copy of To Kill a Mockingbird. To our surprise, he didn’t laugh. Instead, he offered his classroom after school hours and donated a shelf from his own home. “Books can change minds,” he said, his eyes crinkling. “Start small, but dream big.”

The Finch Club got to work. We collected books from anyone who’d spare them—old textbooks, novels, even a dog-eared poetry collection from Salma’s uncle. I donated my copy of To Kill a Mockingbird, though it pained me to part with it. We made a sign with Farida’s careful handwriting: “Shonapur Library: Read, Think, Share.” The first day, only a few kids showed up, but soon, adults came too. Rahim, the old man, borrowed a book on gardening and started talking to us about his roses. Amina brought her daughter, who loved fairy tales, and for the first time, I saw her smile.

The library became more than a place for books. It was where we shared stories—not just from pages, but from our lives. Rahim told us about his wife, who’d loved to sing before she passed away. Amina shared how she’d taught herself to read after her husband died. The village, once divided by gossip and old grudges, started to feel a little closer. People didn’t just borrow books; they borrowed each other’s courage.

Years later, I left Shonapur for college in Dhaka, but I never forgot the summer of To Kill a Mockingbird. The library is still there, now in a small brick room built with donations. Salma runs it, and she says kids still read Scout’s story, still argue about fairness and kindness. I visit when I can, and every time I walk past the mango tree, I think of those evenings when a single book lit a spark in our village. It wasn’t just about reading; it was about seeing each other, really seeing, for the first time.

Now, as a writer on Vocal Media, I tell stories like this one—stories of small places and big changes, of books that don’t just sit on shelves but live in hearts. To Kill a Mockingbird taught me that a story can be more than words; it can be a bridge, a question, a beginning. And in Shonapur, it was all those things and more.

About the Creator

Shohel Rana

As a professional article writer for Vocal Media, I craft engaging, high-quality content tailored to diverse audiences. My expertise ensures well-researched, compelling articles that inform, inspire, and captivate readers effectively.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.