Summoned

A Short Story, Instructions Included

Caves have an odd smell: mineral, fungal, traces of the feces of bats and the slow rot of silent, blind fish in dark, subterranean pools. I have heard the young men of the village mock each other by sniffing an exhalation and declaring: "Cave breath!" as though it were a mortal insult, some potent hex. I know what they mean, now. Imagine that the petrichor, the rich and pungent cologne that rain dapples soil with, became concentrated, corrupted, and was breathed into the mouth of someone who will never, fully exhale.

I do not like the smell of this cave.

But I have come here with a specific purpose. Given a why, I can stand many a how. I have learned how to summon a cure. My solitude has curdled into loneliness. I think I understand why.

You see, apart from my other duties as a monk, it is my job to teach. I have learned some bitter lessons from doing so. One of them, to my surprise, is learning how to read. I don't mean that most teachers are illiterate, though some verge upon that unhappy state. You remember the sage: "Many learned persons have read themselves stupid." How true that is!

Some people learn to read in a particular way and stick with it for the rest of their lives. Some of them sort this out in childhood, which is a real calamity. Others never get over the zeal of the converted, even if they decided to sign up as adolescents. They read with a specific set of parameters in place, as far as what sort of meaning they are seeking, and what sort of meaning they will find, are concerned. Everyone they meet, on the page or the stage or the screen or in the midst of the local inn, fits into the story they have always been operating under the influence of, and another doesn't really seem necessary. A hero, a villain, a savior, one who is like me, one who is not like me (such a pity). They read it all as their only way of reading allows.

I've lost faith in teaching because it taught me to be attentive to character. Thought and word and deed are the parts that make it up. That is as true of your character, or mine, as it is of the character of Beowulf or Odysseus. Your character is excellent, or it is not. If you pretend to read, or let others do all of your writing, or lie, or cheat in other, contemptible ways--if, for example, you feign illness or affliction in order to steal advantages that you do not deserve--it's just not on, really. That sort of thing is epidemic in the classrooms of today. Their faith is no help.

They have been taught to think that repeating answers that other minds came up with, to terribly important questions, is fine. It's not. It's a symptom of indoctrination, not education. Unless you've found truth.

You should want to find your own answers. If someone offers to show you how to find them, you should take that offer. Showing you how to sort things out for yourself is not doing it for you; it's just showing you how it can be done well. Not the only way of doing it well, of course. You'll find your own in time.

The trouble is that I am afraid that I have been reading others this way for too, bloody long. As you can imagine, I'm not terribly popular. I am also unfit for conventional relationships of the sort that make solitude delicious and loneliness impossible. Well, there's Benedict, but he's a friend. I do not want to get involved with any more mortals, if you want the truth. We're celibate, of course, mustn't forget that. Ever.

Loopholes exist.

Benedict, who watches over our library at the monastery, clued me in the other day. I've been looking pretty sour, no matter if we're preparing food or eating food or washing up afterwards or praying or fasting or singing or copying the book so important that we've forgotten it's a book--I'm no fun at all, anymore. Benedict and I used to laugh, softly and secretly, at many parts of our little world. He's determined to help me find my mirth, for it is lost. I think this means Benedict is my friend, and I am his. Disappointing him isn't doing my dour mood any good. I hate letting him down, you know?

So he brought me some cabbage and the stewed remains of a rabbit the other day. When I took the plate from him, I was perfectly mystified. You see, we are very serious and deliberate about all sorts of trivial things here in the monastery. Fetching your own vittles without complaint is like a prayer your feet repeat to the floor.

I knew something was up, but I wasn't clever enough to figure out what until I took the plate and found the parchment folded into a little snake under it. He nodded and smiled and off he went, desperately trying to look like himself, as if nothing new or dreadful had been added to the ledger of his choices.

Here are my instructions:

1. Find a private place at night.

This is harder to do than you might think, when you live in a monastery. Thus the hideous halitosis of this cave, you see? Dank, if you'll allow it. This cave is dank.

2. Find a white candle, pristine and unmarked.

No trouble at all. The faithful love their white candles. Actors love their masks.

3. Find a dark mirror, fit for scrying. This you cannot do without. The apothecary about five miles hence is reliable, and if you flatter him, he'll hold his tongue should he ever be asked about your tastes and habits.

You see what I mean about Benedict. I mean, he ought to be quite an unpleasant person, don't you think? He's a fellow named Benedict who became a monk. That's a bit like Cinnamon becoming a baker, or Bob becoming a lifeguard. The jokes and insults murmured about him were prefabricated by his parents' decision. Imagine how badly it would mess with your son's mind, and yours, if you and your mate decided to name him "Father."

I told the apothecary that I have more faith in him than half the saints I pray to and scrub statues of thrice a day. I think my secret is safe. A dark mirror is a funny thing. One can stare into it for hours and never see a thing worth remembering.

4. Find a strong cord. Your belt will do, but do not let it come to any harm. You are already hard to live with. Punishment and penitence will make you insufferable.

I read and obey.

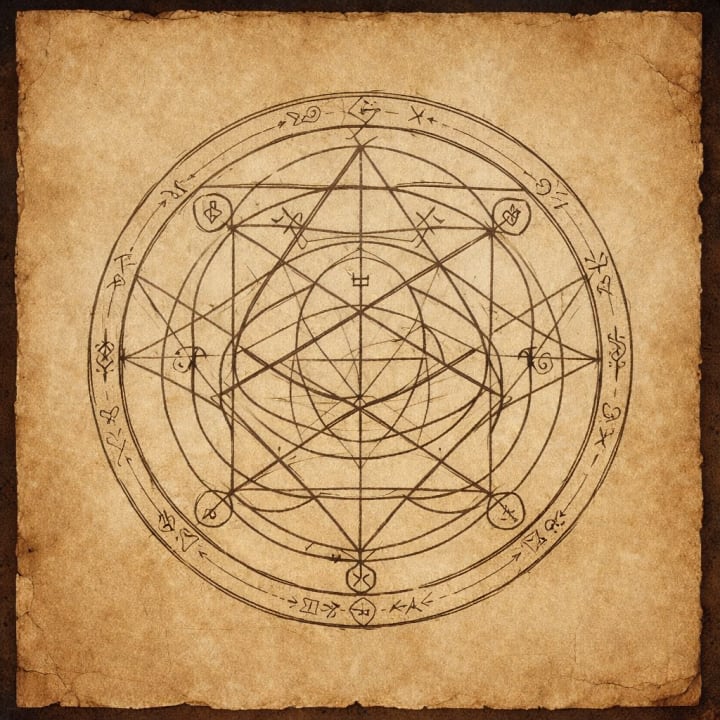

5. Make a circle of protection like the one drawn at the foot of this page. Be very precise. If things go awry, you can bind her in the circle, but watch your step. You drag your left foot a bit, especially since that hound had at you. What a stupid animal.

I've never been one for drawing or painting or that sort of thing, you know? I feel a real hypocrite when I use the same occult devices my students use to "think" and "write" for them to conjure images, but it is fun. I have the idea, I just need help with the execution. That's the part they don't seem to understand, these young characters. You are a user. You can't use an occult device and claim that you did all of the knife work yourself. You can use a trick and confess that while it took care of some of the drudgery, you turned what it sliced and diced into the sensational green curry in the clay bowl on the right.

I think I got the details of the circle right. I guess we'll see.

6. Sit on the edge of the circle. If you've drawn it properly, there's a clear line marking the southern radius. Sit there, on the periphery, mind you. Meditate for as long as is necessary to stop thinking about what you think, so that you can be thinking and nothing but. We've been over this. Too often.

There's a trick to it. Ask someone where they were, on a specific date, at a specific time in the proximal past. This is a disarming question. Lay down your arms, you meditators. Remember what it was like to think, unarmed. It's a great way to end many battles, and sign an armistice in those that will end after you do. There's an extraordinary nun who has written some top notch, mystical poetry that really puts me in a lush, meditative stupor. Hildegarde, I think. I've often thought that it's a shame that she is a nun and I am a monk. Sometimes an emissary from her home turns up here. A bit of brandy can get you all sorts of rapturous descriptions out of the right person. I can see her clearly, or at the very least, I have an idea of her character that makes her beautiful, when I think of her. Just look at this:

Spirited light! On the edge

of the Presence your yearning

burns in the secret darkness,

O angels, insatiably

into God's gaze.

Perversity

could not touch your beauty;

you are essential joy.

But your lost companion,

angel of the crooked

wings - he sought the summit,

shot down the depths of God

and plummeted past Adam -

that a mud - bound spirit might soar.

It could be that, if she were not a nun, and I were not a monk, I would not love her poems as I do. Perhaps we can only be who we are on the page, when the world we walk through is not our home. I've grown rather fond of her. But I can only ever be her reader.

7. Place the candle on the floor to your left. Light it. Place the dark mirror so that it captures the reflection of the candle, but cannot capture any of yours if you sit next to it in the appointed place. You must be able to see what is in the dark mirror without being seen by it, you see. Read this one again. Slowly. Then get on with it.

There's a metaphor here. It is a ritual, after all. The unseen observer? I'll noodle around with it later.

8. Speak the words that follow, firmly but with due reverence. Not feigned reverence, either. I know your tricks. You want it to work, you've got to believe it. Why do you suppose we do all of the praying, nitwit?

He's much more assertive, and sometimes he's a perfect twat, when he's writing. He knows I won't be able to find him fast enough to remember exactly why I angrily sought him out. He's clever, Benedict. But I can read this back to him whenever I like. Oh, how the rage will rush back into my veins when that comes to pass. On the other hand, this might kill me.

9. "Lilith, forgive my entreaty. Know that my heart is true and that I intend your daughter no harm. She will not be bound if you loose her. I understand what she requires of me. She understands what I will require of her. I am not worthy of this boon. Grant what you will." Thrice. Just as it is here, understand?

Boredom is the bastard of repetition. It has two, legitimate daughters: recollection and comprehension. The second one's rather shy, but beautiful--oh, your knees will be water! Benedict taught me that.

10. Wait for her to appear in the dark mirror. She will be pretty shocking. You know the daughter--she tries to make herself useful without much luck--of that idiot who runs that sorry hamlet a few leagues to the west, with more money than taste? Yes, that one. Imagine what her daughter with one of the fallen angels would look like. Brace yourself. Once she appears, say the words below. Do not try to imagine what you would like her appearance to be. She will know. She will be insulted, and probably toy with you in a malicious way that is completely uncalled for, if you bungle this part. Take it from me. The rest is up to you. If things slide sideways and you get the chance, cover the mirror with cloth from your habit and bind it with the cord. Extinguish the candle. Pray. You're not yourself. Sort that out, will you?

"Lilith, that I may honor your daughter as she merits, pray transform her into a shape more pleasing to the eye of a dying animal. Grant what you will."

There she is, in the dark mirror. Ghastly. I suppose that's no surprise. I mean, angry minds with temporary, unstable, subtle or ethereal bodies are about as happy as someone at a crazy stranger's home can be: "What's that doing there? What is that? Do I smell cave breath?" A nasty business altogether. Her face is a collage of mismatched rot.

Now I've said my piece.

Oh, that's certainly a problem.

I dared not hope that she would look this way. I turned from her fresh, dazzling reflection in the dark mirror, and there she was, quite warm and alive. Secretly, of course, I had my foolish dreams about her appearance. Some were not dry.

She's looking me over. She's not pleased.

"Do you enjoy being what you are?" It's an alarming, good question. The clever ones are irresistible, aren't they?

"Not much, of late. What about you?" I take it that it's alright to ask questions. You've seen the foot of the only page Benedict wrote. I'm winging it from here.

"I know this game, and the part I play in it, well. There are many ways to win, and a few ways to lose. I know how to make the most modest of wins feel like an incandescent victory. Unlike you, I cannot grow old, and sick, and die. In turn, you have privileges that are denied me. That is why I came when you called, with mother's leave, of course." She smiles. Her smile is a surgical instrument. It leaves no scar, but I feel it cut.

"You know, Dante condemned hypocrites to wear cloaks of gold with linings of heavy, oppressive lead. You appear to be a lonely monk, but I don't think that's what you are at all. Is this thing on?" She points to the magic circle of protection that I probably rendered improperly. Sorry, Benedict.

I shake my head so as to indicate that she has nothing to fear. I'm struck dumb for a moment or two. This is not the experience I expected, but thus far, it is a good experience. Bracing, sure. So is a hot bath when you haven't had one for a while.

She steps out of the circle toward me. Her movements are not ordinary. I am a clumsy fool, and always have been. I can recognize the ideal that I have always yearned to instantiate myself. It makes me angry, honestly: just how far from bodily grace and beauty I am. I know that's petty, but it is the truth. I move like an animal. She moves like a mind.

"I think I know what's wrong with you, but I'm not sure yet. Would you describe yourself as having good taste?" She puts her hands on her hips and becomes what most humans imagine when they imagine an impatient woman. I think it's a parody of a cliche. I am developing strong feelings for a demon. Right now.

"I hope so. I think long years of disappointment and humiliation have allowed me to make sounder judgments than I used to in my silly, idealistic past. I prefer poetry to theology. What do you mean by 'taste,' exactly?"

She kisses me, quite deliberately and with cool efficiency. I feel as if I've been swabbed for something. She retreats a step, thinking. Her horns are quite lovely, if you want the truth. Symmetrical, intimidating, highly unusual. No one I have ever met before has horns, as far as I know. Certain parties in high and holy offices may be fond of elaborate hats for a reason.

"I understand. You think that because the world is not as it ought to be, you ought not to love it any longer. That is perfectly idiotic, and as someone who styles himself a teacher as well as an ascetical bore hoping for mystical ecstasy, you ought to know better. Everything that is not nature, is culture. You see that the world is not as it ought to be, you are outraged and horrified, so you retreat into cynicism and bitterness. An ego like a parade float. This is the impetus to repair or replace the existing culture. You ought to be teaching and praying and fasting and meditating with that in mind. Write, perhaps? You think illicit dalliances with demons will make you feel better? Quaint. Wrong."

She spits, like an actor cued, on the circle. The cave seems to brush its teeth with tiger lilies. I feel the temperature rising. I am developing strong feelings for a demon. Right now. One of them is fear.

"You want love, but you seem to have no idea what that is. It certainly is not what I have ever come for when I meet a mortal like you. You ought to spend less time tending grapes and more time attending symposia. You find lovable beauty in a body, then bodies, then a mind, then various minds, then families, groups, teams, parties, governments, states, nations, worlds, laws--then the idea of beauty itself, and then the beauty of ideas. Plato knew, you twit."

I follow instructions. With her. I'm at level five. There's hope.

About the Creator

D. J. Reddall

I write because my time is limited and my imagination is not.

Comments (3)

I saw what you did. Not only did you give a nod to my favorite scary lady, Lilith, but you stuck a poem in there for me to read. Great phrases as well. Good luck with the challenge, D.J.

This was a curious place to end up whilst having my lunch. I rather liked it. I'm not sure that I 'got' all of the references but I think that's because I don't have them in my reference library. As always, I like the tone of it and its cleverness and its humour.

Wonderful leftfield take on the challenge