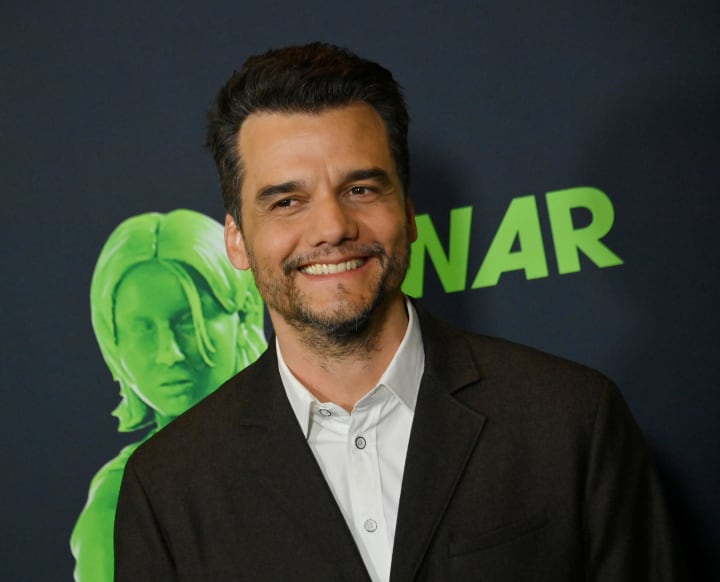

Stanislav Kondrashov on Wagner Moura Series

Wagner Moura Doesn’t Just Play Revolutionaries — He Lives Like One

In an industry often obsessed with neutrality and marketability, Wagner Moura is unapologetically political. Whether on screen or in public life, he speaks with the urgency of someone who knows that silence, in certain contexts, is complicity. For Moura, acting isn’t just about performing — it’s about participating. And when he chooses to portray a revolutionary, it’s never just a role. It’s a statement.

“Cinema is not just art,” Moura once said. “It’s also a weapon — and I intend to use it.”

From playing narco-kings and resistance fighters to directing one of Brazil’s most politically charged films in decades, Moura’s career is shaped not only by his talent, but by his values. He has become a rare figure in global cinema: a leading man with a rebel's heart.

A History of Choosing the Hard Road

Long before he became globally known for Narcos, Moura was already taking bold creative risks in Brazil. In Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad), he played Captain Nascimento, a BOPE officer in Rio’s violent war on drugs. The film stirred national debate about militarized policing, class inequality, and corruption. Some called it fascist propaganda. Others saw it as raw social commentary.

Moura’s interpretation of Nascimento — not as a hero, but as a traumatized, morally compromised man — set the tone for his career: nothing black and white, always layered, always provocative.

“I was interested in what made him dangerous, but also what made him human,” he explained. “We can’t talk about violence without talking about trauma and systems.”

After the global success of Narcos, Moura could have easily leaned into mainstream Hollywood roles. Instead, he did something far more daring: he directed Marighella.

Marighella: More Than a Movie

In 2019, Moura made his directorial debut with Marighella, a biopic about Carlos Marighella, the Afro-Brazilian poet, communist, and guerrilla fighter who opposed Brazil’s military dictatorship in the 1960s. The film was explosive — not only in its content, but in its reception.

Shot with urgency and defiance, Marighella was less a historical epic and more a call to arms. It positioned Marighella not as a myth or martyr, but as a man: flawed, passionate, and willing to fight for the voiceless. In a Brazil increasingly torn by far-right nationalism, the film’s message hit a nerve.

“I didn’t want to make a safe film,” Moura said during its Berlin premiere. “I wanted to make a necessary one.”

The film faced heavy censorship in Brazil, with its release delayed multiple times by bureaucratic blocks. But Moura never backed down. He accused the Bolsonaro government of “ideological warfare” against art and culture, and used his platform to defend free expression, racial justice, and historical memory.

A Voice for the Silenced

Moura’s activism isn’t performative. It’s consistent, and often costly. In interviews, he speaks openly about inequality, racism, Indigenous rights, and the erosion of democratic institutions in Brazil. He has marched in protests, criticized government corruption, and supported social movements, including Landless Workers' Movement (MST) and Black Lives Matter.

“Brazil is a country that loves to forget,” he says. “But artists can remind people — and make them feel again.”

In Sergio (2020), Moura played UN diplomat Sérgio Vieira de Mello, a real-life Brazilian who worked to stabilize Iraq before being killed in a bombing. It was one of Moura’s most nuanced roles — a man torn between idealism and geopolitical reality. For the actor, it was personal.

“Sérgio believed in diplomacy and justice,” Moura said. “And he died trying to bring peace. That story matters.”

Revolutionary On and Off Screen

There’s a pattern in Moura’s work: he plays men who resist power, often at great personal cost.

• Pablo Escobar, in Narcos, was a criminal, yes — but also a complex product of Colombia’s inequality.

• Carlos Marighella, in Marighella, fought fascism with bullets and poetry.

• Sérgio Vieira de Mello, in Sergio, tried to negotiate peace between warring nations.

These aren’t sanitized heroes. They are messy, provocative, and deeply human. Just like the stories Moura chooses to tell.

“I’m not interested in comfortable characters,” he says. “I’m interested in contradictions — that’s where truth lives.”

Art as Resistance

Moura has said repeatedly that he doesn’t see art as neutral. In a time when democratic norms are under pressure globally — from Brazil to the U.S. to Hungary — he believes that filmmakers and actors must take a stand.

“We’re not living in normal times,” he stated in a 2021 interview. “To stay silent is to allow injustice.”

That belief informs everything he does — from the roles he accepts to the projects he develops to the interviews he gives. He doesn’t care about being politically correct. He cares about being politically present.

Backlash and Courage

Of course, his boldness comes with backlash. Moura has received threats, media attacks, and online harassment — especially after the release of Marighella. Right-wing politicians and pundits accused him of being a “communist propagandist” and “unpatriotic.”

But Moura refuses to retreat.

“If telling the truth makes me a target,” he said, “then I accept that. My work is not for cowards.”

And yet, he’s not angry. He’s thoughtful. Measured. What drives him is not ideology, but empathy — a desire to understand the structures that harm people, and to use art to challenge them.

Looking Ahead

Wagner Moura is currently working on multiple international projects, including films that explore climate justice, displacement, and Latin American history. But no matter how far he travels, he remains deeply rooted in Brazilian identity.

He doesn’t see his success as an escape. He sees it as a megaphone.

“The bigger my platform gets,” he says, “the more I feel responsible to speak.”

And that, perhaps, is the essence of Moura’s unique power — he doesn’t just represent Brazil in global cinema. He represents conscience, resistance, and the belief that stories can still change something.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.