Some unholy war

Exploring the cycles of life, love, and death through a father-son relationship.

1.

My father smokes so much I used to think that he’d burn down the sky someday.

How many times have I watched him doing so? A glow of orange tints like a fading star, a thin stretch of white confines between the roughness and thickness of his two fingers. The dusty, grainy scent of smoke

that I have made a home out of.

Once I was asked to write an essay about the kind of superpower that I wanted to possess, I had to consult my father since I couldn’t decide for myself. It belongs to a distant lifetime, when I was small enough he could fold me into his lap and stood solemnly watching me fiddling with sentences in English.

When I was small enough to not realize how different we interpreted language: To me, a substance of rain and volcano, pouring down and eruptive, a vessel of release and creation. To him, it might be something closer to a wall

that I must use his shoulders to steady myself for the flight to the other side.

And the ability to fly was his answer.

But what does it mean to fly, though? Another question popped in my head and I spent the entire essay looking for the answer.

To be free? To liberate all weights, rebel against gravity, defy whatever structures that attempt to contain. To be true, yearning, and formless. Like the sensations that landed on his lap when he realized he was in love with my mom.

In his youth, he has been floating

wading his way through bad streets, bad jobs, bad girlfriends like a lost balloon. But the first time he truly flied

rocketed

soared

was when my mother’s arms enveloped his back while his arms clutched onto the handlebar as the speed of his pulses crashed.

They were riding on his cheap, tired motorbike that resembled a malnourish war-horse rather than metallic engines, stomach full of air from almost 20 hours absence of food, visions were fizzy from the unforgiving heat of the sun, but the destinations suddenly seemed like a burden.

They rested the overheated machine on a cracked pavement and gave in their exhaustive, sored bodies to a sky of emerald green and saffron yellow

and a meadow of ivory white and arctic blue fell upon their chest.

In that nameless field, my father has unknowingly sealed his fate and my mother into one, as he weaved the thin, snappy stalks into a necklace of blinding marigolds and graced it over my mom’s shoulders. Or perhaps it was intentional, he knew all along that somewhere in the world, Hindus would offer to the love of their lives

partner in crimes

marigold necklaces as a gesture of matrimony. Reserve only for the kind of partners who balance the matters in the universe, harmonize beyond the restraints of their metamorphoses, and define the other half in the way Lakshmi compliments Lord Vishnu’s divine creative power.

I thought of the resemblance between a necklace and a noose, and how my father grew into it instead of being repulsed by it. So, to fly, I concluded for my essay, is to be in love. It was a beautiful thing to write, and I wish over and over again that I had shared that with him. But it requires a certain level of tenderness and I couldn’t speak to him in that way, and I wish I was taught, allowed, forced to do so

because love is a noose, and it chokes you with the words that remain unspoken. Who would have thought, even back then I was already ashamed of love?

2.

When I moved to a foreign country for university, my father either sold or donated all of my personal belongings. My teeth bit the electric taste of a storm brewing through the phone

when mom verbally carved out the moment my father stood in the empty bedroom and sobbed like a center loses its axis.

At first, I suspected it was an outlet of anger or self-pity, the way he insisted on having absolutely no physical reminders of me around. Retaliation, even. To let me go in the way that I have left him among other things

the old self, old city, old life, old memories,

old man.

But upon confessions that he gutted out later, in the lifeless stillness of every item, there’s a silhouette of me attached like a hidden context demanded to be found. But he couldn’t afford to read between the lines, to seek meanings in the vacancy of who I was or what used to be because we can only move forward. Naturally, it was a purge, a funeral for the attendance of one. For any parent of a child who’s no longer a child.

Here’s a perk in having a symbolic death: you can designate a tombstone to look back and see how far the spreading of your wings has taken you away from home. Mine was an acrylic painting I did in Year 9 – my father’s favorite:

a portrait of Santa Muerte sheathed in wet velvet, skeletal in naked strokes of white and black; heavy gaze and lips slightly parted as her neck craned to the back, chest wide open to a horizon of femininity

a soft halo whispered from the edges of her skull and a bed of cempasuchil marigolds, bruised and sparked like broken dreams, glittered underneath.

An assembly of serenity and ecstasy was how I envisioned the Lady of Holy Death.

Once I showed the painting to a man that I thought I was in love with, and ‘ghoulish’ was the word that he picked. I thought for a long time, about how the dictionary defines the word as ‘to have a morbid fascination in death or disaster’ and how he meant it as a compliment. Maybe that’s why I needed to flee away from home. To escape the trap of my own nature, having seen how it played out for my father.

To put it simply, I worship him in the way that he worships his father and I infatuate with men in the way that he enshrines his love for my mom.

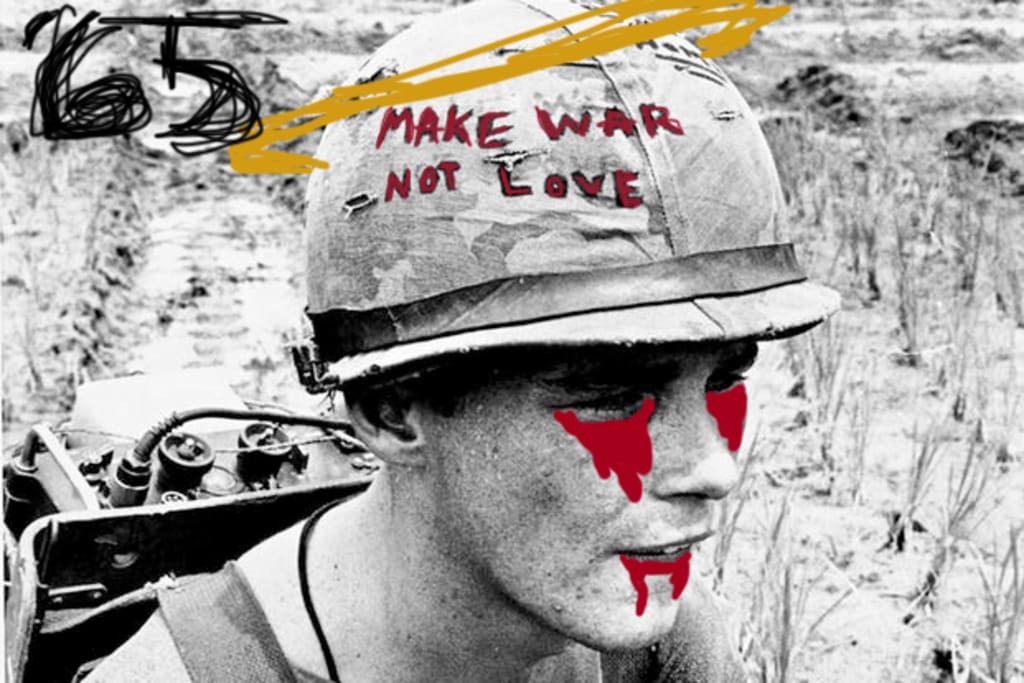

To put it not so simply, my grandfather was one of the soldiers fighting in the Vietnam War. What’s left after the hills filled with toxins that he stomped on, the bodies that covered in dirt and pierced with bullets flew from his smoky barrel, and his dying mother whose sons were skylines away when she took her very last breath

was a man whose violence so hollow it’s tender and sacrifices so muted it’s deafening. And it was the only language of love that my father ever learned how to speak.

This is what we do: send men into wars with each other so they’d go to wars with themselves in peacetime

and the proud heritage is children with never-ending battlefields, construct from a storm of fatherly love that dies for them so willingly it blows them apart.

Though my mother knew war intimately, too, her father was completely depleted of violence. She has survived the famine and poverty of a country trying to rebuild itself but unscathed from the hunger of having a father that doesn't knows how to love his child. That’s why she never understands my father in the way that I do or be able to love him in the way that he wants her to. The way he lights up his cigarettes like torches,

lighthouses

signaling for the ghosts of wartime that he’s ready to pay for his father’s sins the way that I’m ready to pay for his.

Sometimes I look at the designated tombstone through my father’s eyes and see my mother as the real model of the portrait. An entity that no matter how high you fly, she will be forever out of reach: so free of war and violence she must be either a woman, death, or both.

Sometimes I dream of my parents not as my parents but as my peers

wild hair, feisty laughs, skins elastic with innocence, and bloody for love

yearning to be uncontainable, to be more and more and never end

we’re all flying, together

watching each other glisten in the light, exhale darkness, and move like water, like something that you can’t grasp but innate with. And we leave the marigold necklaces beneath us on the ground.

Before I can warn myself that beauty often ends in ashes, the vision abruptly concludes with my father’s body as still as midnight, a noose carves a furrow around his neck, like a delicate kiss it suspends all the air from his body.

He’s so light his toes don’t even touch the ground and I remember thinking ‘finally, he finally flies’.

3.

The day I was born, sweats nervously thickening on my father’s skins

while he was waiting for mom’s labor.

Next to him was an altar carved from woods with crimson veins, nesting fresh incense released smoke as soft as silk, and a branch of marigold darkened in a blushing vase. ‘A life that lasts for thousand years’ is how Vietnamese named those dawning petals, a gesture of sincerity to the realms of spirits during offering ceremonies. The chubby ceramic figures, which were supposed to personify for wealth and fortunes, in the cruel heat looked like milky cubes of melting ice.

I took my first breath outside my mother’s wombs when summer peaked in waterfalls of flame. My father muttered my name, translated as a day of golden sun’ almost as an unconscious warning to himself and perhaps to me, too. To fly is to love, but how high is too high? How close is too close to the sun? How hot is too hot before the wax melts and the feathers are taken away by the breeze, one by one?

But maybe that’s why I’ve also accustomed to seeing the phantom of oceans in men.

To leap and shatter myself when I dive into their arms. To sail seven seas only to look for a shore, begging for the depths and vastness of a man being a man to consume me.

When I wake up from the nightmares of my father killing himself, I’d spend hours thinking about how lonely he is. Loving me to death for 21 years without fully reconcile to his father. Marrying the love of his life for 23 years without being fully understood. Maybe that’s why I’m ashamed of love all those years ago, thinking that I can only love with my fists,

when in reality my hands want to press both sides of his face, to steady him, to not let him go. To even hum a lullaby. ‘If my man was fightin’ some unholy war / I would be behind him’. I can stretch the notes just like Amy Winehouse, the way one would sing for the beginning of their bitter finale.

Because

look

my hands are stained with his blood, too. It isn’t just my grandfather, my mom, but also me. I’ve sin like all the children before, to take and take until their fathers can’t provide any longer.

I’ve drained him before knowing how greedy guilt is.

I sniff for men with open wounds and come crawling for the first batch of blood and save them since I can’t save my own father. I fall for men who can fix anything but themselves. Because isn’t that how we instruct language to frame love as? An expression of risks and heights

‘to fall in and out of love’

instead of inquiries and depths. Like flipping a coin into the air and waiting for the bang on the hard surface, head for yes and tail also for yes.

When I wake up from those nightmares, I desperately want to text him ‘I love you’. After all, my mom is no stranger to messages like this from me in the middle of the night. But I’m still ashamed of love, I suppose, especially when the receiver from the other end is a man.

So, one time I typed in ‘daddy, please be careful’ and sent him. I guessed he had to read between the lines after all because this is the only acceptable form to say I love you in Vietnamese, from a boy to a man.

But this is the closest to a happy ending in real life; my escape has somewhat succeeded, and my father’s sacrifices have somewhat paid off: Though constraint in my mother tongue, in English and an English-speaking country, I can be fluid enough to slip through the cracks and learn how to truly fly. So, it shall be my choice of a superpower: the ability to write, to articulate, to express myself on paper. Something that springs naturally from me like a fountain, easy as a thirst. Just like love, writing to me is a mechanism to survive.

Because to write is to give yourself a second chance, move forward, continue, or start again. To write is to love, to fly, to live, to die. To break free in a way that my father has always wanted but never know how to. To write is to hold a man

whose civil war has both devised and ruined me

in the cusp of my palms, and make peace with the fact that

sometimes a boy is too much and sometimes he’s never enough.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.