We were almost ready to close when two Buddhist monks walked in and ordered twenty large cheese pizzas to go.

“Sorry, we lock up in five minutes,” I said. “We’ve got a few leftover slices but …” I looked over at Kelly, who stood behind the register with a sour grimace, a knotted dish towel being slowly strangled by her pink-tipped hands.

‘We’re closed,” she said, staring at the counter so they couldn’t see her eyes. “There’s a twenty-four-hour Pizza Hut a mile down the road.”

“Yes, we know,” the shorter of the two monks said. “But Brother Phap Dong prefers your pizza. It’s his last meal. Tomorrow, at sunrise, he’s setting himself on fire. You’ll help us, yes? Phap Dong has a beautiful heart.”

The monks smiled, all mystical and serene, practically oozing loving-kindness from their big shaved heads. They wore dark maroon robes and plain brown sandals; the shorter one was Asian, Vietnamese, I think; the other monk was a Jersey guy like me. I wasn’t certain but he resembled some guy my older brother used to beat up in high school.

“Wait a minute—he’s setting himself on fire?” “Yes—for the benefit of all sentient beings.”

“He asked specifically for your pizza,” Jersey Monk said. “Phap Dong says he knows you. Sometimes you visit the sangha.”

Kelly looked at me and scowled, as if she’d just seen my naked photo and been disappointed by the reveal. There was a monastery ten miles outside town and sometimes I stopped and listened to the talks. I wasn’t a Buddhist but much of what I heard made sense and I had started reading books by the Dalai Lama. I was trying to develop my mind, avoid being the lunkhead behind the pizza counter I seemed fated to become. In college I had studied literature and philosophy for two semesters before I’d dropped out, too broke to keep paying tuition, too nervous for the ball and chain of a student loan. I knew a little something about debt. During my senior year in high school my father went bankrupt and put a bullet in his brain.

Kelly could tell I was wavering. The monks didn’t say anything but they didn’t leave, either. They folded their hands in a prayer position and waited. From my visits to the monastery I knew they could stay that way forever, that they lived in the now.

“It’s going to take at least an hour, maybe longer,” I said. Before Kelly could throw her hissy fit I told her to go home. She wouldn’t have been much help anyway; her job was handling the register—she’d never made a pizza in her life. I flipped the oven switches and pulled some dough from the fridge.

“Thank you, Flynn,” Asian Monk said. I was shocked that he knew my name.

“You’re part of the sangha, giving yourself to help others, to help brother Phap Dong. Your heart, too, is beautiful.”

Kelly snorted and rolled her eyes, grabbing her purse from under the counter, shooting me a “sucker!” look as she blew past the monks and hustled out the door.

“So what’s the deal with twenty pizzas this time of night?” I asked.

“We’re down on the Green,” Jersey Monk said. “Phap Dong wants to share his last meal.”

For the past two weeks about fifty activists had set up camp on the Green at the center of town, mostly college kids but a few unemployed corporate types, too, along with some hippie grandmothers and a few wandering stoners. My wife Kasey and I had meant to check it out but hadn’t found the time.

“We lead mindfulness sessions on the importance of a peaceful heart,” Asian Monk said. “Even with Right Intention it’s easy to fall into delusion.”

“Isn’t setting yourself on fire kind of delusional, too?”

“There is controversy, yes, but there is also a tradition of self-immolation among Buddhists. In the Lotus Sutra, it speaks to cultivating the perfection of generosity, the giving of inner wealth. The offering of the body can be a powerful step on the bodhisattva path.”

Jersey Monk walked toward the soda case, his face twisted and grim. I could tell he disagreed but didn’t want to speak. In New Jersey we only set things on fire if there’s insurance money involved. He grabbed a Coke, pulled the cap, and drained half the can.

“In many ways we’re all on a course of self-immolation,” Asian Monk said. “There’s so much greed and violence and delusion. We’re burning the planet that sustains us. Is filling your car with gasoline any different from what brother Phap Dong is doing?”

“It hurts a lot less.”

Jersey Monk snorted, hiding his face behind the soda can. I started kneading the dough, rolling it out and working it through my fingers, stretching it thin and pressing it back into a ball. It was all muscle memory, my hands like ghosts, squeezing and rolling.

I slid the first batch of pies into the oven and checked my phone: three new messages from Kasey, each one a photograph of a potential tattoo: a flower, a fish, or a baby bird hatching from its shell, the finalists for the open real estate on the back of her right calf. It was her new addiction, turning herself into the Illustrated Woman. Kasey was a cardiac tech at the County Hospital; during her down time she’d send photographs of different designs, mostly for herself but some for me, too. So far I’d avoided getting inked. Kasey had all kinds of ideas for what we could do with my skin but I was hesitant, reluctant to traffic in permanent marks.

I texted her back about the last one, the baby bird breaking from its shell: idk either. A month earlier we had found out she was pregnant. It was totally unplanned, unexpected, and in the morning, we had an appointment at the clinic to terminate the pregnancy. We were both pro-choice and had serious doubts about bringing a child into this mean, fucked-up world, but as the appointment approached, Kasey had grown sullen and irritable, her Catholic upbringing hard to shake.

The monks drifted toward the corner, their heads bowed in contemplation as they slipped inside a booth. Their equanimity was unnerving. I knew Phap Dong; he was my age, maybe a few years older, a French Canadian who’d dropped out of college and bummed his way to Asia looking to screw Thai chicks on the beach and get stoned every night. Instead he wound up a Buddhist monk.

He liked to play basketball, had a pretty good hook shot At the monastery we’d played some hoops in the parking lot one night, and even though he was barefoot and wearing that goofy robe, he still beat me, draining four jumpers at the end to edge me by a point. He had this wild, beautiful laugh, a real graceful soul; he’d elbow you out of his way to grab a rebound but somehow do it mindfully, as if his rebound was your rebound, too. I’d never met someone who seemed so at peace with the world. Why would a guy like that self-immolate? My father’s suicide: that I could understand, even though at the time I hadn’t seen it coming and I didn’t do a damn thing to help him. I was only eighteen, I told myself, as if that mattered.

After the game, as we walked back to the meditation hall, Phap Dong reached into his pocket and handed me a slip of paper. Before I could read it he placed his hand over mine and whispered, “Later.”

It was almost dark, the lights from the parking lot fading as we walked the tree-lined path toward the hall, Phap Dong holding my hand gently, the warmth of his palm spreading across my fingers, both of us silent, the crickets the only sound as we moved down the path. The instinct to pull away was strong and embarrassing, the lunkhead in me screaming, push him away before he kisses you. Another man had never held my hand before, not even my father. When I was still too young to cross the street alone Dad would place his hand on top of my head to guide me, as if he were steering a hand truck. Phap Dong held my hand as if it were the only way to walk beside another person.

Later that night I opened the slip of paper as I lay in bed. It was a poem: Buddha in Glory by Rainer Maria Rilke. Kasey was asleep beside me, still wearing her scrub shirt from the hospital, her bare legs pulled up in a fetal position, an open bottle of Xanax on the nightstand.

I read the poem three times, certain phrases holding my eyes as I scanned the page.

Thick fluids rise and flow…your flesh, your fruit

A billion stars spinning in the night.

Now you feel how nothing clings to you; Your vast shell reaches into endless space.

To Phap Dong those words must have felt liberating but to me endless space seemed terrifying. I wanted something to cling to me. As I settled in beside Kasey, my arm draped over her shoulder, my legs tucked against her hips, I kept thinking about the poem, especially the last two lines: Now you feel how nothing clings to you; your vast shell reaches into endless space.

The next morning I stood in the shower, slowly waking, the hot water streaming over my face as I heard the bathroom door creak open and felt a rush of cool air, the curtain sliding back as Kasey joined me. Later that month, when she missed her period, I thought only of that morning, the two of us making love beneath the spray, thick fluids rise and flow, your flesh, your fruit, your vast shell reaching into endless space.

When I asked Phap Dong about the poem, he was vague but I kept pushing him. Finally he said, “Perhaps what you see as fixed is fluid instead.”

Was he talking about my father? I’d found him in our driveway, his body slumped over the steering wheel of our Honda, the windshield speckled red, a wasp perched on the dashboard as if guarding its kill. What could be more fixed than that?

“The next time you sit in meditation,” Phap Dong said, “focus on the vast endless space.”

*

The pizzas were still baking so I walked over to the monks, hoping they might explain self-immolation.

“Why not ask Phap Dong yourself?” Jersey Monk said. “Come see the encampment. It’s important to stand with those who oppose violence and delusion, if for no other reason than your soul demands it.”

“Many years ago my parents were killed by your country’s bombs,” Asian Monk said. “We lived in Quy Nhon, by the beach. My father was a fisherman, a Buddhist, a peaceful man. My sister and I were visiting our grandmother in another village or we would have died, too. Why does a country send planes seven thousand miles to kill a poor fisherman and his wife? What kind of delusion causes this to happen? Whenever hatred threatens to consume me I think of the thousands of your countrymen who went into the streets, who said, ‘We must stop.’”

He rose from the booth and walked toward the door, his head bowed as he stared through the glass into the dark parking lot. Behind the counter I grabbed the wooden peel and slid a pie from the top oven, cheese bubbling up in blisters of mozzarella and marinara, the crust a rim of golden brown.

Jersey Monk peered over my shoulder as I slid the pie back in the oven and lowered the heat.

“Really, you should come with us,” he said. “We walked here, you know. We were hopeful you would drive us back.”

“You’re out of luck. Our delivery guy left an hour ago and my wife has the car. She won’t be here for…” I checked the clock. “…at least thirty minutes.”

“Perfect. She’ll come with us, and you can talk with Phap Dong.” He set his hand on my shoulder. “He asked for your pizza, but he asked for you, too. He wants to speak with you before he leaves us. He said you were in crisis.”

“How does he know? I’ve talked to the guy maybe five or six times.”

“Some of the brothers…they have a way about them. The third time I visited the sangha Phap Dien …” He nodded toward the Asian Monk. “…walked up to me and hugged me before I said a word. He vowed that my hurt was his hurt, too, and together we would walk with the pain until it left. They just know.”

He grabbed a napkin, wiped his lips, and walked out from behind the counter. “Let’s sit for a while, the three of us,” he said. Phap Dien turned from the door and joined him in the middle of the floor, the two monks folding their legs into the lotus position, robes bunched around their feet as they straightened their posture and closed their eyes.

I wanted to join them, but I was too much in the grip of what Phap Dong called monkey mind, my thoughts racing around helter-skelter breaking everything in their path. Kasey’s pregnancy had thrown us, a challenge to our vow to remain childless. There was too much crap in the world, and over the years plenty of it had smacked head-on against our lives. Our relationship was founded on scar tissue. Kasey’s step-father had abused her; there were addiction issues, depression; she’d been a cutter back in high school.

Even before my father’s suicide my family was a wreck. My mother left when I was twelve; my older brother later joined The Marines without even saying goodbye. I hadn’t heard from either of them in years. My father lost his business, lost our house; put a gun against his head and fired. It didn’t help that Kasey and I were broke, her salary gobbled up by student loans, my own paycheck a lousy fourteen bucks an hour even though I’d been running the place for three years. Bring a child into the world? No thank you, yet I still regretted that we’d never see our baby’s face looking up at us in wonder.

I began boxing up the pizzas, pulling each pie from the oven and sliding it into the box, aware of the monks’ steady inhalations, my movements instinctively synched to the rise and fall of their breath. In my pocket was the poem Phap Dong had slipped me at the monastery. I took it out and read it, even though I had it memorized. Now you feel how nothing clings to you; your vast shell reaches into endless space. Was it mocking me? How did endless space reconcile with my life of constraints, twelve hours a day behind the pizza counter, a too-small apartment in a tired suburb, a marriage steeped in a shared sense of doom? Phap Dong had wanted to show me possibilities, but where were they?

I closed the lids on all twenty pizza boxes and packed them in the delivery bags, five boxes per bag, the Velcro straps sealing the heat while we waited for Kasey. I grabbed some napkins and paper plates and threw them in a bag, the scent of all that pizza surrounding me as the monks opened their eyes, raised their heads, and turned to me with peaceful smiles.

*

The monks sat in the back of the Honda, the pizzas stacked between them as we drove toward the Green.

“During break I went down to the maternity ward,” Kasey said, staring out the window at the darkened houses lining the road, her weary reflection filling the glass. “There were twelve new mothers. According to the statistics at least five of the newborns were unplanned. Two mothers will experience some form of post-partum depression, and one will regret her decision to have children. The Pew Foundation did a study.” She turned from the window. “I thought you might appreciate the data.”

“We can always cancel if you’re not ready. The doctor said …”

“I know what the doctor said. Just let me feel bitter, okay? We’re not canceling.”

I found a parking spot a block from the Green and shut the engine. Kasey zipped up her jacket and yawned.

“If you’re too tired you can wait in the car,” I said, but already she’d unhooked her seatbelt and opened the door.

“Let’s take a few selfies to prove we were here.”

The monks and I split the pizzas and Kasey grabbed the bag of napkins and paper plates as we headed toward the encampment. I was curious and excited too, turned on by the possibility of revolution, even one doomed to disperse once the overnight temperatures dropped below forty. Imagining a different way to organize the world seemed important and necessary, and though I was too much of a grinder to ever join them, I was grateful for their presence.

Phap Dien walked beside me as Kasey hung back.

“You sense my turmoil and you’re here to offer wisdom, right?” “Not really. The wisdom that you need…”

“—is within me?”

“No, it’s within the Dharma.” He smiled. “The scent of all this pizza, it’s beautiful, isn’t it?”

We turned the corner and spotted the Green up ahead, the dark illuminated by a circle of lanterns. Through the trees we could see the tents and the makeshift shelters, refrigerator boxes and tarps rigged up between the tents in a tight circle, a First Aid sign affixed to the largest structure. The Green was public space; there were three port-o- johns along the perimeter and a bronze statue of George Washington by the entrance. It was past midnight, and the camp was quiet but as soon as we entered someone pounded a drum, and a young guy in jeans and a hoodie emerged from the dark.

“Hey, the pizza monks are here,” he shouted, and a few people came wandering out of their tents, blankets draped over their shoulders as they shuffled toward the food.

“I’m Clay, thanks for the grub,” the young guy said.

We shook hands as he led us to the “dining hall,” three picnic tables pushed together beneath an awning of clear plastic. The air held a crisp chill and Kasey huddled against me while the monks unloaded the pies.

The campers soon gathered, circling the tables as they grabbed slices and offered thanks. Across the Green I saw Phap Dong pacing alone in meditation, his head bowed, hands in a prayer position as he walked in a long, looping circle.

“Is he the one who gave you the poem?” Kasey asked. “That’s why we’re here, right? Go talk to him.” She patted the keys in her pants pocket. “If it gets too cold, I’ll wait in the car.”

“Come with me,” I said. “Maybe it will help …” “Go,” she said, pecking my cheek, dismissing me.

Clay and some other dude lit up a joint after they scarfed down their slices, and I knew Kasey would join them once I stepped away, her old inclinations hard to shed.

Phap Dong looked up as I approached, slowing his pace until I joined him at the edge of the camp. The moonlight caught the sheen of his shaved head, a soft glow circling his crown. To his left, beside an old wooden bench, was a large red gas can, five gallons, enough to burn down the whole encampment. Some of the gas must have spilled; the vapors cut through the night air.

“Flynn, I’m happy to see you,” he said.

“Our menu promises free delivery.”

“But not after 10:00 PM,” he smiled. “Others would have sent us to Pizza Hut. You have a beautiful heart.”

“So they tell me. But it feels plug ugly, most of the time.”

“Walk with me,” he said. “Sometimes the dharma finds us when we need it most.” I wasn’t in the mood. “Are you really going to do this?”

“We’ll know when it’s done,” he said. “My intention is good…but I’m scared shitless.” He stopped pacing, reached into his robe and pulled out a cigarette, lighting up. “I quit four years ago. The cycles of samsara keep spinning.”

“Don’t do it,” I said. “Walk away.”

He took a long drag on the cigarette and pushed the smoke out through his nose. “The monk Jinzang, many years ago, wrote that we offer our bodies to repay the Buddha’s kindness; to pay homage to him and create merit for all sentient beings. I was a prick before I found the Dharma. I owe the Buddha everything. Perhaps when people see what I’ve done they’ll be willing to act. The Buddha teaches that the end of suffering is possible. People must know that.”

“No one will learn a damn thing. They’ll think you’re crazy.”

“Maybe I am. But if one person follows the path…maybe that one person is you, Flynn.”

“Don’t even go there. You ordered twenty pizzas and it’s my job to make them. That’s why I’m here.”

“I’ll be dead in a few hours. Don’t lie to me, or to yourself. Avoid that dishonor, please. That’s not why you’re here.”

“Why did you give me that poem?” I asked.

“Because it’s true. My body, this will be my offering. What will you offer, Flynn? You told me about your father once. In certain moments he’s alive. In others he is dead. The same is true for all of us. Nothing is fixed. Your vast shell reaches into endless space.”

The moon threw shadows across the grass. Phap Dong flicked his cigarette toward the gas can, the ashes falling like dust. Across the Green someone started playing guitar, the familiar chords of a song I knew but couldn’t name. Phap Dong coughed twice and tossed the cigarette to the ground.

“Now you feel how nothing clings to you,” he said. “Find your pain and make an offering to it. Your vast shell reaches into endless space.”

“Where is this space you keep talking about? My whole life is a trap.”

“You don’t see it, but it is there. I didn’t see it until I found the Dharma. I’d still be banging teenager prostitutes in Thailand if I hadn’t found it. Find your pain and make an offering.”

He picked up the gas can and unscrewed the cap, inhaling the vapors, and for a moment I thought that this was it, self-immolation, but after a few long, unsteady breaths he replaced the cap and sat down, crossing his legs and resting his hands on his knees, the gas can at his side. He closed his eyes and began to chant, a whisper as light as his breath.

I still had questions, but he was done with me, his body stiff and corpse-like, his head tilted toward the ground. I turned and walked back to the group.

As I reached the tents the scent of marijuana grew strong, and sure enough, Kasey was high. Years back I’d smoked some too but had quit after Dad shot himself. When I found his body there were three joints on the seat beside him. All those years together and I never suspected that he smoked. The joints were spotted with blood and little specks of what I guessed were brain matter. Later a friend offered to set the Honda on fire for the insurance money but instead I washed the blood from the windshield and steam-cleaned the seats. Kasey and I still drove it. It was our only car.

In the days before Dad’s suicide it was just the two of us in a house in foreclosure, my father parked on the sofa staring at old sitcoms, a .38 and a box of bullets on the table next to his coffee mug, me in a perpetual state of half-baked, rushing off to Kasey’s house to get stoned in the basement and screw. I never did a damn thing about the gun or those bullets; I just walked by day after day, as if they were a platter of Saltines and Cheese Whiz. My father didn’t leave a suicide note but left instead a single bullet in its regular place on the table, maybe hoping I would follow his lead. I still had it, tucked inside the toe of an old white sock in the back of a drawer. The police had kept the gun and those three bloody joints.

Back at the tables I was greeted by two-thirds of Kasey’s naked ass, her pants tugged down from her hips as she showed Clay and the monks her favorite tattoo, an elaborate garden of sunflowers and roses and long flowing vines. Jersey Monk’s stare made me want to slap him, but I knew Kasey enjoyed it, her exhibitionism stoked by a fresh joint and the attentions of other men. Over the years she’d cheated a few times and I wondered if the fetus, the baby, whatever you wanted to call it, was actually mine. It was an ugly thought, unfair; not that it mattered. We had an appointment at the clinic in less than eight hours.

Phap Dien approached and led me from the table. He touched my shoulder and I waited for him to say something, but he remained silent, the steady pressure of his hand grounding me, and together we breathed. I heard Kasey giggling as she pulled up her pants and grabbed a final hit before leading me back to the pizza.

“Have a slice,” she said. “I know the chef. He’s cute.”

At that moment I hated pizza. The night my father shot himself I brought him two slices during my break—his last meal.

A serious-looking guy, clean-shaven in a baggy flannel shirt, walked over with a copy of Noam Chomsky’s On Anarchism. He started talking about participatory democracy and alternate modes of production, the Mondragon co-op in Spain. He seemed worried that we’d think the occupation wasn’t serious, that it was all about hanging out and getting high.

“Read Sheldon Wolin and Richard Wolff,” he said. “Read Antonio Gramsci. You can’t understand the world until you understand Gramsci.”

I asked Kasey if she was ready to leave. Jersey Monk hustled over and thanked me again for the pies.

“Tomorrow night we’ll be at the monastery, sitting in honor of Phap Dong. Please join us.”

Across the Green I saw Phap Dong seated beneath the oak tree, the gas can on his lap, his hands raised toward the sky.

Kasey and I said goodbye and started walking. What will you offer, Flynn? Phap Dong had asked. I still had that Rilke poem folded in my pocket. Nothing clings to you…your flesh, your fruit…even my own child was a fleeting condition. Sometimes the only permanence I felt was that single leftover bullet in the back of my drawer.

We climbed into the Honda, and I turned the key. Kasey reached over and stroked my hand.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I won’t smoke anymore. That was the last time.”

It was a lie; we both knew it, but I held her hand anyway, our warm breath forming vapor-ghosts across the windshield.

“You still want to do it, right?” I asked.

“Who knows, but I’m going to. Now is not the time. Maybe never--but certainly not now. We both know it.”

On the dashboard, above the radio, was a divot where a bullet fragment had lodged into the dash. I’d pulled out the fragment, but the hole had remained. When my father shot himself the Honda, paid off the year before, was all he had left. Except me, who had done nothing to save him. With my free hand I touched the dashboard, pressed my thumb over the divot. At the time one of the cops had suggested I junk the car, that with head wounds the shatter effect was too great; you could never find all the fragments.

Your flesh, your fruit …thick fluids rise and flow. Now you feel how nothing clings to you. Your vast shell reaches into endless space.

Find your pain and make an offering, Phap Dong had said.

I held onto the steering wheel but couldn’t drive away, the windshield fog dissipating as the Honda grew warm. The divot on the dashboard—it was a vast, endless space.

“I’ll be right back,” I said.

Clay and the Chomsky guy looked up as I cut across the Green, the monks, pizza boxes in hand, heading after me as I hurried toward Phap Dong, who was still seated with crossed legs, the gas can balanced on his lap, his right hand clutching the nozzle as he stared into the dark.

“I’ve been thinking about Medicine King,” he said, his voice shaky and weak. “The Lotus Sutra explores his self-immolation, for the benefit of all sentient beings.” He took a long, labored breath. “I wonder, before he lit the fire, if Medicine King wanted to throw up, too.”

“Doesn’t matter,” I said, and reached for the gas can, grabbing the handle. “This is what I offer.”

For a moment he resisted; then his grip released, his fingers falling from the nozzle as I pulled the can away from him. I waited for him to rise, to demand that I give it back, but instead he unfolded his legs, stretched his arms, and burst out laughing.

“My intention remains,” he said, breathing softly, “but thank you.”

Jersey Monk handed him the last slice of pizza, and Phap Dong, smiling, wolfed it down.

“For the benefit of all sentient beings,” I said, “—or maybe just you and me” Exhausted, I lugged the gas can back to my father’s old Honda, emptied all five gallons into the tank, and hopped behind the wheel, Kasey snoring beside me as we drove into the vast endless space.

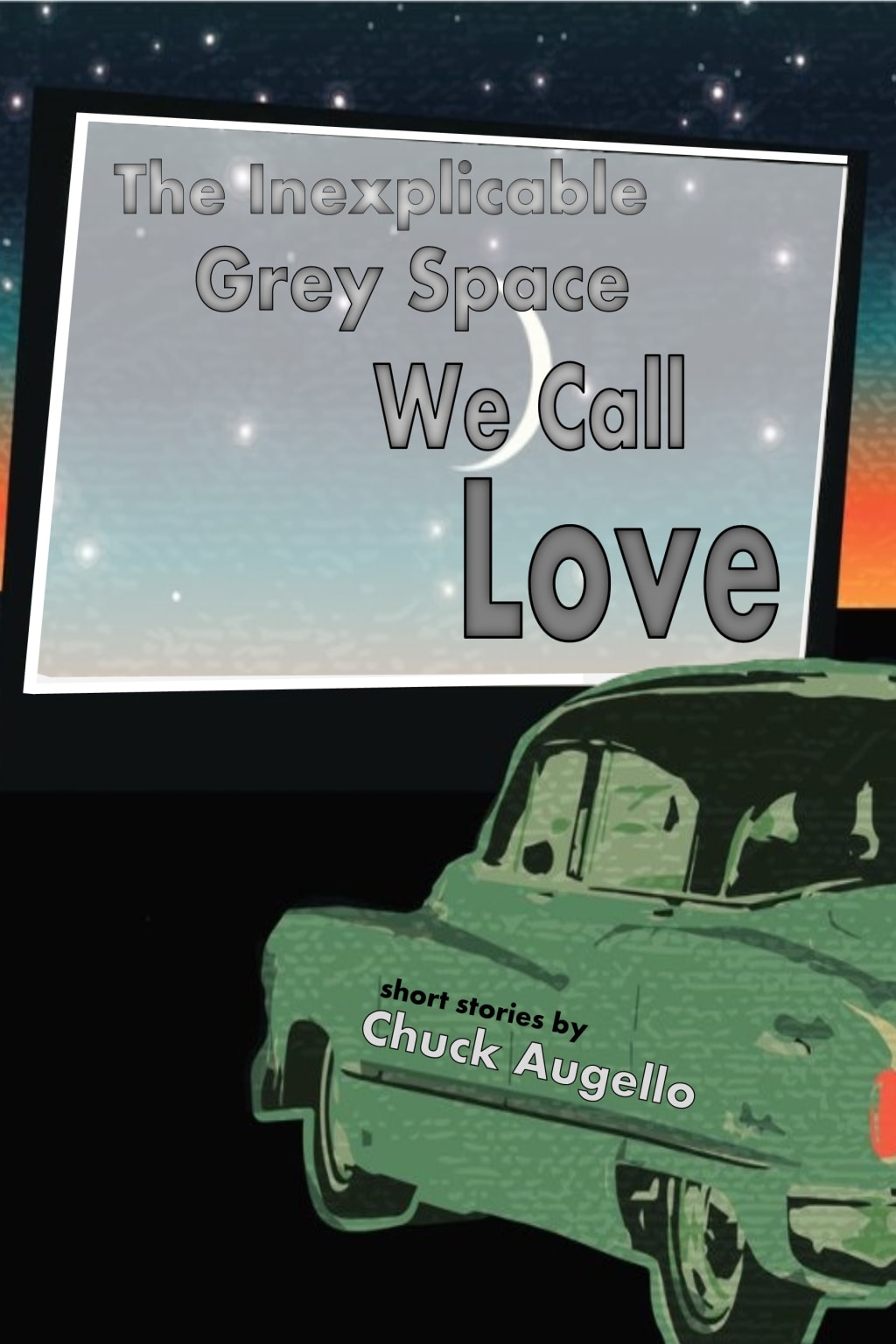

About the Creator

Chuck Augello

Chuck Augello is the author of The Revolving Heart, a Best Books of 2020 selection by Kirkus Reviews. His most recent is Talking Vonnegut: Centennial Interviews and Essays (McFarland), an exploration of the life and work of Kurt Vonnegut.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.