After nine hours on the road we were exhausted and bleary-eyed, dizzy with headache, in no shape to drive even one mile more, so we did what the phone voice said and took the next exit, grasping at the promise of comfortable lodging and a warm fork and spoon.

“As long as it’s clean,” Lisa said.

“As long as it’s quiet.”

“As long as the shower is hot. And of course free breakfast.”

Her whole family was crazy about free breakfast. Lisa adored complimentary muffins and miniature pastries.

To stay awake, we recited our favorite breakfast foods, confessed to the guilty pleasures of a frosted scone. Life was so much better before blood sugar became a thing. We’d reached the age where everything but spinach had become a threat. The world was in freefall. Conversing with extended family had been deemed a carcinogen. Everyone had a temperature and a permanent rash.

“And so on,” Lisa said, because it was all too much.

Eight minutes later we arrived at the Ice Hotel. We smiled, exhausted and relieved.

“Wow, I’ve read about this place,” Lisa said.

But she hadn’t. This particular Ice Hotel was neither sleek nor Scandinavian nor appropriate for vodka ads on the back page of The New Yorker. It was a giant ice cube on the side of the road in a rusty town, an ice cube with a front door and a sign reading “Vacancy.” It was cloudy like an ice cube, so you couldn’t see inside, made of tap water instead of sparkling spring and so within our harried budget.

‘I’ve never been inside an ice cube before,” Lisa said, as if most people had. We grabbed our bags and entered.

“Welcome, welcome,” the manager said, skating toward us and scooping our luggage. The floor, like the walls and the ceiling, was made of sheer ice. Lisa and I linked arms and tried not to slip.

“Tonight you’re in luck. We had a cancellation so I can put you in a suite,” the manager said. He was tall and ruddy, dressed in a pea-coat and plaid scarf, a red ski cap pulled an inch from his brow-line. His breath-fog formed clouds resembling birds floating between us, and we tried not to stare. Lisa and I were crazy about birds.

“A room for the night, yes, of course,” the manager said. “You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

“Isn’t that from …?”

“It’s from here, too. More poetry than policy, of course; you can leave anytime, but once you’ve spent the night, why would you want to?”

“Why would we ever want to leave?” Lisa asked.

“Precisely. Once you’ve experienced the ecstatic numbness of ice, why would you opt for the world at large?”

Lisa and I traded looks. Too peculiar? But we were cold and tired, wracked with headache and not thinking straight, the floor ice seeping through our soles, our toes curled and trembling.

“Do you offer free breakfast?” Lisa asked.

“Complimentary muffins in the dining room at 6:00 AM,” the manager said. “A selection of tiny scones second to none.”

We handed him our Visa and signed in.

“This was a tragic town until we built the Ice Hotel,” the manager said. “Pain was simply everywhere: sorrow, addiction, rage, and despair; a ubiquitous fear, headaches and indigestion.”

“And so on,” Lisa said, because it was all too much. Except for the headaches and the fear, she and I had been lucky.

“When I was twelve, I sprained my ankle chasing rabbits in the yard, and my dear Mother treated the sprain with ice,” the manager said. “At once the pain subsided, and the lesson stuck. Ice was the answer to everything. I sewed ice packs into my pockets, slept in a tub of shaved ice, and never felt pain again. As I watched my beloved city suffer, I knew the answer was ice.”

By the time we reached our room, Lisa was shivering.

“The rooms are heated, I assume.”

His face pickled as he dropped our bags at the door.

“You’re in the Ice Hotel,” he said. “There’s always a transition, but trust me, you’ll feel nothing. To be cold, to be numb…it’s a beautiful thing.”

We took the key and entered our ice room. On any other night we might have been frisky, hotel sheets being a favored aphrodisiac, but nine hours of driving had extracted a toll. At least the bed had blankets and Lisa had long abandoned sheer lingerie for functional flannel. Still, we couldn’t sleep, and predictably, our midnight thoughts turned grim.

“Job loss, bankruptcy, foreclosure,” I said.

“Heart attack, stroke, cancer,” Lisa said. “Hair loss and bleeding gums.”

We watched a lot of TV, could recite the debilitating effects of medication the way we’d once remembered song lyrics.

“Dementia. What if I forget who you are?”

“What if we both forget?” Lisa said.

We reached across the bed and held each other, my hand slipping beneath her nightgown, stroking the cooling planes of her skin.

“If we feel nothing, perhaps it won’t matter,” I said, opening to the manager’s philosophy. “He’s right—it’s dreadful out there. It’s cold in here, sure, but I’m starting to feel safe.”

“Protected.”

“Numb.”

“And so on,” Lisa said, because it was all too much.

“If everything is ice, will it matter if I look into your eyes one day and see blanks instead of you?”

She offered her face, but our frigid lips felt nothing. And then there was sleep.

When I awoke, the bed was empty, the bathroom door ajar. Lisa stood in the tub as snow fell from the showerhead, beautiful white flakes coating her black hair, dusting her pink shoulders. She opened her mouth and caught a snowflake with her tongue. It didn’t melt; she swallowed it and caught a second one, her red toenails barely visible beneath an inch of packed powder.

A month later, (or was it years?), we still lived at the Ice Hotel, hypothermic and blue-skinned, frigid and numb.

“It would have happened eventually,” I said.

“We couldn’t stay warm forever.”

“There’s safety in ice.”

“And our headaches are gone,” Lisa said.

Sometimes we missed them. But at least there was free breakfast.

At 6:00 AM, when the complimentary muffins first arrive, they are piping hot, and we’ve learned to be early, nostalgic for the fleeting scent of the freshly baked. At the corner table in a room made of ice, we tear off chunks of blueberry muffins and eat from each other’s hand, sharing these last vestiges of comfort in a world gone cold.

When we finish, our palms are still hot, and we press them together, sealing the warmth between us.

“And so on,” Lisa says, because it was just enough.

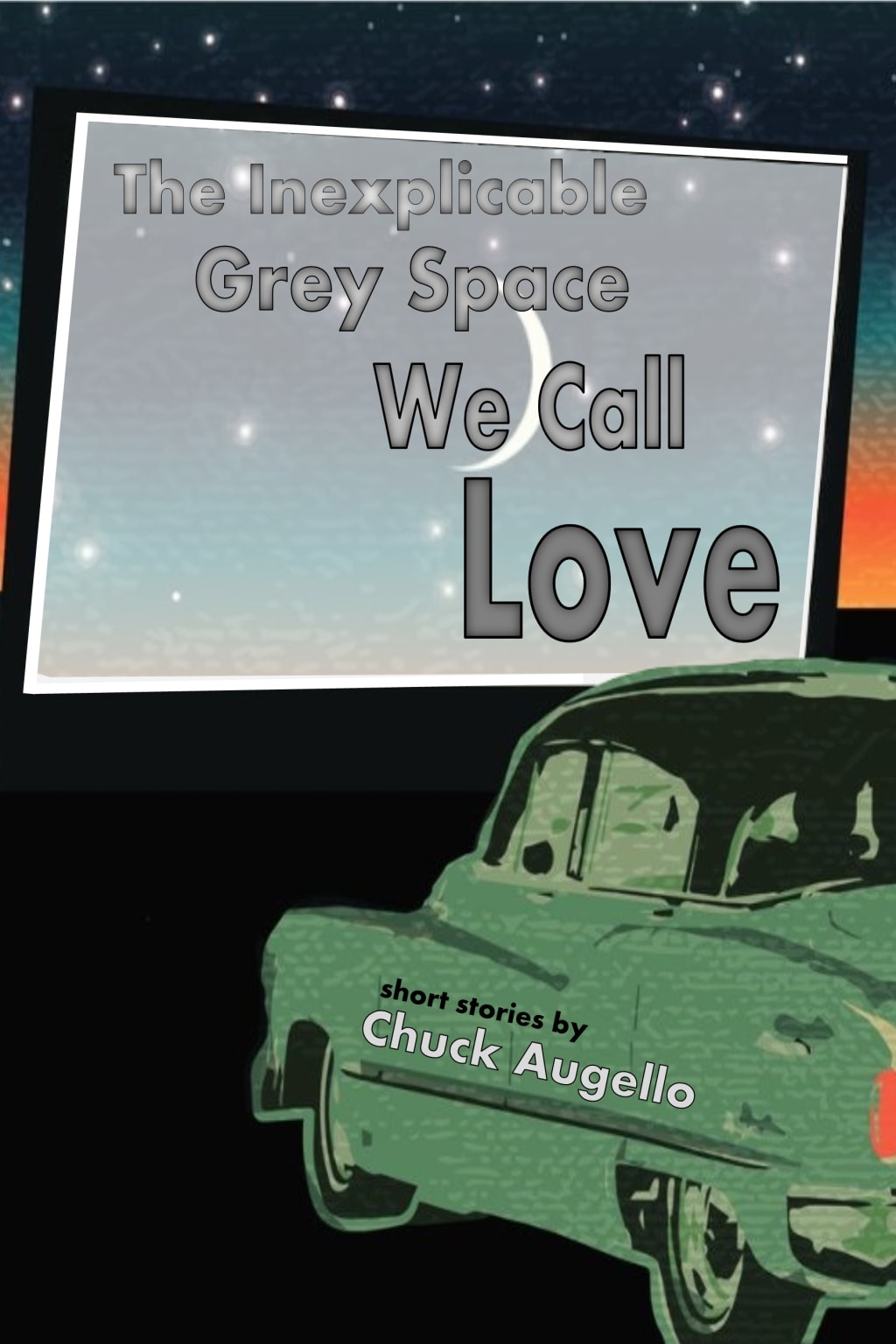

About the Creator

Chuck Augello

Chuck Augello is the author of The Revolving Heart, a Best Books of 2020 selection by Kirkus Reviews. His most recent is Talking Vonnegut: Centennial Interviews and Essays (McFarland), an exploration of the life and work of Kurt Vonnegut.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.