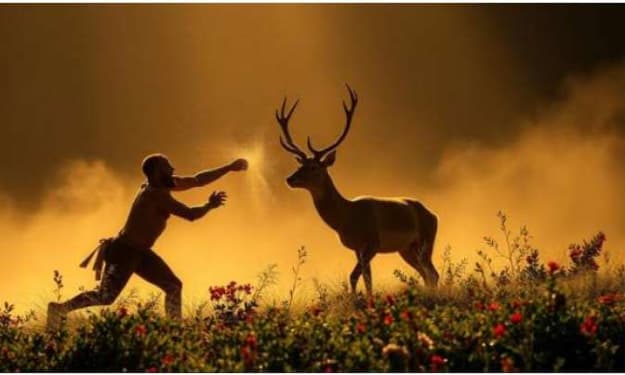

Nana and the bear.

The polar bear was hungry but Nana didn't agree to be dinner.

“Nana, nana, tell us a story!” As soon as Uki spotted Nana, she raced across the wooden floor of her grandmother’s living room, her small bare feet slapping hard on the worn grain. “Please please please, will you tell us a scary story Nana?” Uki opened her arms wide and threw herself at her grandmother giggling.

Nana sat stiffly upright on the corner of the sofa and smiled, her dark eyes crinkling at the corners. Always they wanted scary stories. Such kids these days. One minute playing their video games on that Switch Nintendo thing. Next it was the scary stories.

“Oh little Uki, so pretty with your dimples and smiles. I don’t want to tell you another silly story. Besides, I’d like to hug your sister too.” Nana beckoned to Tali who tried to hide in the open doorway. “Tali, come give grammy a hug.” Nana’s voice echoed in the tiny room where the only other sound came from the beech logs crackling in the fireplace.

Tali hung her head, her loose brown hair fell across her forehead and hid her eyes. She didn’t like Nana; Nana wasn’t mean or anything, it was just that she smelt like fish and Bengay and maybe a little bit of pee. Tali could never get used to it. Not only that, Nana frightened her, her voice was so loud sometimes. And maybe sometimes her eyes were too bright, too sharp for a little old woman with shaky hands and sensible flat shoes. Tali lingered in the doorway and tried to make herself as small as possible.

“Come now child, you can’t leave poor old Nana waiting for a hug, can you?” Nana reached trembling hands out, her wrinkled fingers fluttered like tired birds, and her loose white skin on her spotted arms hung and waved gently. Tali hid her face in the crook of her elbow. Long moments passed and Nana’s hands slowly fell to her lap, fingers still trembling slightly. “Whenever you’re ready my little one, I can wait.” Tali steadfastly looked at the floor.

Uki, wriggled herself up on the sofa. “Tell us the story of the bear that tried to eat you Nana, Tali likes the part with the bear.”

“I do not.” Tali found her voice.

“Well I want Nana to tell me the story of the bear.” Uki settled herself across Nana’s soft lap and grabbed her papery wrinkled hands to her chest. “I’m not scared Nana, nothing can hurt you.”

“Very well Uki, I will tell you the story, but you have to remember it wasn’t the bear’s fault. Not at all. He was just hungry, he was in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

“I know.” Uki whispered. “But you ate him anyway.”

“Oh Uki, I didn’t eat him, you remember what happened don’t you?”

Tali pressed her back against the door. “It was the long night and Nanoq had been hunting for days but he didn’t catch anything. He was so hungry he came too close to the settlement.” Tali’s eyes glittered. “And you were out on the snow too weren’t you Nana?”

A hard old log in the fireplace cracked in the heat with a sudden sharp snap; orange sparks rushed up into the chimney. Nana’s face glowed yellow and white in the firelight for a moment, then the shadows raced back to darken her face but her eyes still sparkled like old ice under a full moon.

“Yes child. I was worried. I had a sick child in the illu. Your father was just a baby Uki, and his father, your grandfather -Ataa was on the snow with the dogs. Two weeks he was gone, hunting for something to eat, but the seals were hard to find, their holes were hidden in the ice and the fish were swimming too deep. And the snow - it kept falling as if it would never stop. Tali, your father was sick; his little face was red and hot and his eyes were closed so tight I was frightened. When he cried, he would cough until his little body would shake. I was so worried; I had to get help for him. But who would come? It was the long night, and we were poor so we were nobody. No one would miss us, no one would care if the ice came and filled us up when we slept. And with your Ata gone, I had to do something.

“What did you do Nana?” Uki couldn’t take her eyes off her grandmother.

Nana adjusted herself on the hard cushions of her old sofa. “I did what any good mother would do, I radioed Ata, to tell him what had happened and I prepared to leave the illu to get help.”

***

I wrapped the baby in the thickest animal skin I had. Ata had killed a caribou three winters ago, and I folded and stitched the brown and gray pelt to make a blanket lined with fur both on the outside and inside. It would keep the baby warm as long as I didn’t stay out too long. Somehow, the cold felt colder in the half light, it got under your furs, under your flesh when you weren’t looking and froze your skin in goosebumps that never seemed to go away. I hoped it wouldn’t get to the baby or if it did, he wouldn’t cry too much. He was such a tiny little thing. I hoped it was just a cold and it would pass. Whatever I did, I had about two hours to get into town. There was a storm coming. A big one and two hours were barely enough time to get into town but I had to try; little Tonraq needed medicine.

My plan was simple. I just needed to get to the storage shed on the far side of our lot. Inside, I’d start one of the snowmobiles we winterized, come back to the illu to get the baby, then we’d follow the frozen river back to town. There was a nice old doctor who would see him, and we’d ride out the blizzard in town where at least there’d be people. Our homestead was 5 miles out of town and though it was quiet, no help would come for us during a blizzard. Inuks are all family but whiteouts are terrible. You could get lost, turned around in the dark and the drifting snow. You could get hurt or worse, you could be followed.

There were things that came out in the ice. Dark things that hid in the shadows and could smell you no matter where you hid or find you no matter what you did. I knew the stories. Never walk into a storm alone. Never answer if someone calls you by your name. And most of all, never ever stray from the path. Crying babies could draw the spirits, and animals get hungry in the endless night.

Yet there I was, wrapping myself in layers to keep warm, carefully tucking my ulu, my half moon knife, into my belt and slinging my long rifle over my shoulder. I hoped I wouldn’t need either but better to have it and not need it right? I could feel the storm gathering in the half light, weighting the dark and sending little shocks in the air. Later, when I’d come to my senses, I would wonder if I had gone mad, as if some winter demon had taken hold of me and led me out into the snow.. But at the moment, all that I could think about was the doctor’s kind face as I brought my firstborn to him, outrunning the storm chasing at my heels.

When I opened the door it had already started snowing. Light fluffy flakes floated quietly down as if they were feathers. Now and then a puff of wind would snatch them up in a tumbling circle and whisk them around my legs. My stomach immediately lurched and I felt my heart hammer in my chest. I wondered for the thousandth time, if I was doing the right thing. To leave the poor baby alone, even for a moment felt like I was about to fail as a mother. What kind of parent would leave a sick child? Should I take him with me?

Breathe. I told myself. Just breathe.

All I could do was make the best bad decision I could. Without Ata, I felt lost, floating, frightened. But I had to do something.I closed the door behind me and shuffled onto the porch, my snowshoes thumped and scraping on the snow covered wood. Behind me, I could still hear Tonraq crying, his little voice muffled by the heavy door. I had to be quick, the light from my flashlight barely penetrated the dark but in the distance I could see the humped shape of the shed at the far side of the lot. In the summer when the snow thawed, I could get across the stony black ground in two minutes. But with deep snow and the heavy shoes, I hoped it wouldn’t take more than five minutes. But those would be the longest five minutes I ever lived. My baby was alone in the illu. My eyes were fixed on the shed. And I didn’t look back. That was what saved my life.

***

“Was that when the bear came Nana?” Uki’s eyes were wide and staring, her little mouth open. She clutched Nana’s hands as tight as she dared.

Tali took a careful step towards the sofa. “The bear came to the illu. It heard Ata crying. It came to see.”

“It was hungry Nana.” Uki squeezed her eyes shut.

“Yes my little darling. It was hungry. So it climbed up on the porch but I didn’t see it in the falling snow.”

***

I started the snowmobile with a few pulls of the cord. I clicked on the lights and was surprised to see it blink on and cut out in seconds. Fucking piece of junk. I cursed it. It would save my life but I cursed it. I hit it too but I hardly felt it through the thick Swanys I impulse bought from Amazon.

And it was in the sputtering watery light from Ata’s spare snowmobile, I saw the white shape of Nanook as he stood upright and rocked the door of the illu. I could see the outline of light widening around the doorframe as he rocked the heavy wood. The sound of his chuffing and grumbling filled the air with his breath. He was easily eight feet higher than my door. Maybe I imagined it, but Tonraq’s crying sounded even louder. At that moment, all I remember was the soft touch of shadowy snowflakes as they lay on my face and melted like ice cold kisses drifting in the wind. I could feel the warm engine tumbling between my knees and in my ears the sound of my voice shattering into brittle shards as I screamed at the bear.

***

Tali crept closer to the sofa. “Tell us about his eyes Nana. Tell us what happened when he saw you.”

***

The great white bear half turned. His paws were as big as the shovels Ata used to clear the snow. And his heavy head lifted into the wind. I could hear him sniff the air. Searching for the smell that made the shrieking sound. His eyes skittered left, right, then fell onto the blinking headlight of my Artic-Cat; eyes like black holes filled with yellow glowing light reflected like flames from my sputtering headlamp.

I felt it growl before I heard it. The sound rumbled like an earthquake across the soft snow, up past the drumming of the engine, into my stomach; from there I felt it shake my heart and freeze my lungs. For a long moment, I couldn’t breathe..

Nanook shambled off the porch. The timbers groaned as he moved. And then he was on the snow galloping toward me faster than I could run.

Perhaps I screamed even louder. Perhaps I passed out for a moment. When I opened my eyes Nanook was almost on me. I must have grabbed the throttle on the Cat, because when I remembered to breathe I was flying across the snow. I dared a quick look back. Nanook fell behind but only just. In the half light, I couldn’t see much of him, only the gray bulk of his body barreling through the heavy snow, throwing it into the air as if it were mist and nothing else. And his eyes -I was completely wrong. In the twilight, Nanook’s eyes flickered, like flames as if lit from within. Perhaps they were. I don’t know if I imagined the whole thing. But no bear’s eyes ever held cold fire like the one that chased me.

And no bear in the history of our people ever caught a snowmobile, but Nanook did.

There was a roar, as if the sky opened to release a storm. The air seemed to tear, to rip apart and I sensed the swing of a giant paw as it caught up to me.

All I knew next was that the Cat went skating sideways. I heard metal grind then snap. The engine began hissing, coughing, and with it the damn headlight flickered completely off. I pushed the accelerator as far as it could go and prayed as I scrunched into the seat. Behind me the sound of teeth snapping on frozen air filled my ears.

I couldn’t see. Shadows leaned in the dark before me. Would I slam into a tree? The shed? I was so turned around I didn’t know what was around me. I prayed I wouldn’t hit a snowbank and serve Nanook his dinner without a fight.

Blink. The light came on and stayed on. I thanked the sea Goddess Sedna. Snow rolled out in front of me like endless waves. Bellows from behind. Hot steam trailed from my nostrils.

Think.

The Cat sounded bad. I could hear metal grinding. The engine hissed and hiccupped and my speed on the snow sped up and slowed down. It wouldn’t last long. What could I do? What would Ata do? Ata would use the rifle. He would tie the accelerator with something. String. Fur. And he would aim at Nanook and shoot him in the head.

Could I do it?

I reached up for the strap of the rifle. It wasn’t there. I patted myself down. I couldn’t find it. Panic bright and white flared in my head. There was no rifle, somehow I had dropped it.

All I could do was run with a demon bear behind me and miles between the town and me. I headed for the river, my thoughts flitting on little Tonraq, his crying had called the demon bear. I was certain of it. Would I ever see his little face again? What gave Nanook the right to take him from me?

The snow smoothed out as I hit the ice but the Cat wouldn’t make it. The hissing grew louder. The sound of gears stripping and grinding loud in my ears.

And then I knew what to do. I would make Nanook fall through the ice. I would draw him out, let him chase me to where the ice was thin enough so that he would fall in. I knew he could swim but, once he fell I could…

I didn’t know what I could do then. Maybe he would get hurt in the ice. Maybe it would give me time to escape. Maybe it would confuse him. But it was the only thing I could think of.

***

“You were so brave Nana.” Uki curled herself into Nana’s lap. If it were me I would punch Nanook right in his snout and send him home! Uki made two little fists with her hands and shook them.

Nana smiled to herself. The innocence of her grandchildren.

Tali sidled up to the sofa and sat down as far away as she could. She looked at Nana and then at the fire. She felt she could almost feel what Nana was feeling. But stranger than that, she could almost feel what the bear felt too. It was as if she was there inside both of them, Nana trying to save her child, the bear starving as the winter drove his food away, both of them knowing only one would survive.

***

I headed out to where I knew the river was deepest. In the summer it was more than 20 feet deep. Sometimes I would swim there in the clear cold water and wait for the fish. Most times I could take at least one with my speargun. It was there I took Nanook.

Please Sedna,I prayed. Please, don’t let the ice be thick.

It was all I could do. Nanook’s claws crunched behind me. I squeezed the throttle as hard as I could. It could go no more, it met the cold steel of the handlebars. I could go no faster.

Further we ran him and I. Out past the shallows where I skipped rocks as a girl. Out where Ata would take his boat fishing. Out to where the river met the ocean, where the waves slowly froze and the ice could get so thick you had to cut holes one foot deep to fish.

And then I heard the sound I prayed so desperately to hear. Cracking sounds. Like icy whips lashing the night air. The ice in front of the Cat started fracturing. I dared another look back. Nanook was growing tired. His heavy body further away now but still behind. And as I looked. I felt the Cat tip sideways. I’d loosened enough ice for it to break off in a large chunk. I was almost afloat.

Behind me Nanook paused. I could still see the lambent yellow glow from his eyes. His breath plumed around him yet he kept plodding forward. He knew. I couldn’t run forever.

It was then I decided, I would run no more. The Cat would either shut down or sink under me. I had to decide how to end this. And praise Sedna, it came to me. I would crash the Cat into him. It weighed more than 600 pounds. If I did it fast enough, maybe it would scare him. Maybe even hurt him. Maybe it would kill him. If it didn’t, he would kill me. And the ice would come and take Tonraq as he slept.

Sedna give me courage.

I looked to the heavens, in the sky the first stirrings of the Aurora painted long green ribbons against the hard pinhole stars.

Please take care of my baby.

I turned the Cat around and grabbed the accelerator for dear life.

I bet Nanook’s eyes must have widened in surprise. Dinner didn’t often arrow right towards him.

But I wasn’t dinner.

The tired Cat groaned and ground her gears. She trembled and juddered and ground her way to the top speed she was capable of. I guessed I was doing at least 60. Nanook’s huge mouth opened. I could see teeth the size of bullets. His red tongue. His heavy paw as it raised and the flash of his yellow eyes. Then I threw myself off the side. I hugged my head as tight as I could and rolled.

Snow can be as hard as rock. It can break you open, it can cut you. It can bury you for a thousand years and there you’d remain forever, frozen in time. I hit the ground hard. I know my heavy coat saved my face but a thousand shards of ice cut through my leggings, tore foot-long gouges into my thighs, my side. As I rolled I felt my shoulder snap. I heard it as clear as day, it sounded exactly like the small sticks I would break to start fires in the illu. Then the pain came. Sharp and bright as icicles melting in the sun. I screamed. Sedna forgive me, I screamed as my body rolled towards Nanook.

The Cat hit him with a heavy thump. He bellowed in anger, in fury, in pain. Both of us were marked that night. He roared his hurt into the cold air, it sounded like thunder rolling across the ocean. I half raised myself to see. Miracle of miracles, the headlamp still worked. Nanook lay on his side breathing hard. There was no blood. Perhaps he was only stunned. I pushed myself to my knees. I felt the bones in my shoulder grate against each other. I blinked back tears that froze in the corners of my eyes. My nose felt sticky and clogged, I could barely breathe.

But I knew I couldn’t let Nanook get back up. I forced myself to my feet and the pain crashed into me like a tidal wave. Sharp needles of what felt like glass on fire traced a burning path down the left side of my body. My left arm hung limp and loose at my side. They told me later, it was broken in four places. I hugged it close to me and limped to Nanook. His great belly raised and fell with his breathing. His eyes were closed. I reached for my belt, fumbling for the moon shaped knife I kept with me since I was ten years old. I always kept it close, closer than my shadow. Now it’s familiar outline filled my hand. I drew it and knelt next to Nanook’s great head.

I whispered every prayer I’d ever learned. I prayed to Sedna, goddess of the sea. To Nerrivik, to Anguta, god of the dead.

***

“Then what happened Nana?” Tali crept closer to her Grandmother.

Nana’s eyes brightened, her white hair fell around her narrow face in gentle waves. “Oh little one, nothing happened. I hit Nanook so hard, he fell asleep. So I went back to the illu and shut the door as tight as I could shut it and prayed for help. I’d already radioed your grandfather, he was on the way back home. I think the great bear learned his lesson. He didn’t come again that night.

Nana smiled gently. There was no sense scaring the children any further.

***

But Nanook wasn’t dead, and when he awoke, he would still be hungry.

I prayed to Sedna, goddess of the sea. To Nerrivik, to Anguta, god of the dead. I prayed for the spirit of the bear and I plunged my knife into his throat as he slept. The blood that sprayed my hand was hot and wet and sticky. The heat of it filled the air with soft red mist. I could feel his great heart as it pumped his spirit into the snow, onto my skin, onto the cold ice in a thick crimson tide. And I hated myself then, for taking his life. But I had others to take care of, his death would bring life to many. I knew as I kneeled there, with the snow falling heavier now and the sound of the wind whispering in my ears. I knew Nanook’s spirit would mark me, and I was no longer afraid.

I could feel it singing in my head already. It felt like a weight had been lifted from me. As If I were in chains my entire life and I was suddenly free. I could smell the air, sense the sky. Even the pain in my body dimmed, replaced by a slow heat. And in the heart of me, I felt that first strong beat that would never leave me. I feel it still.

I can’t explain it more than that. But something wild took hold of me that night. Something uncivilized, untamed. It’s in the gaze of my eyes. In the way I walk without a care and talk with a voice that fights to form words in a mouth that doesn’t feel like mine alone. I’m restless now, uncomfortable in my own illu. I can’t sit still for too long. I can’t stay quietly among my own people. The ice calls to me. The open space beckons. The cold air knows my name and it whispers to me in the cracks below my door, in the spaces around my windows.

And whatever Nanook passed to me, I know I passed it to my own children. I smell it on Uki, on Talli. Sure as winter snow follows the summer sun, the bear lives with us and we will carry his spirit when there is no longer any place on the snow for him to roam. Sometimes, I suspect, Nanook came to me to die so that he could be reborn. But that’s just an old woman’s imagination.

***

Talli smiled to herself. She loved hearing the story of the bear though she refused to admit it. She could smell the snow outside their house. She could hear the ice crystals forming as the air grew colder. Sense the slow fish as they swam beneath the frost speckled sea. And sometimes she imagined she could feel herself run across the white ice, her body low to the ground and powerful as she searched for something to eat.

End.

About the Creator

Mitchy Mitch

Just another human, trying to figure out which way is home.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.